As I write these words, American pundits and political junkies are struggling to come to terms with some curious, even alarming, developments. Donald Trump has claimed the Republican presidential nomination while advocating a ban on Muslim immigration to the United States and the construction of a wall along the Mexican border. While many would blame his rise on the particular dysfunction of the G.O.P. or of America’s political culture more generally, a larger context makes that view impossible. A populist and sometimes xenophobic campaign succeeded in persuading British voters to leave the European Union. Marion Maréchal-Le Pen has risen as a charismatic new star of the French right; Germany buzzes with the possibility of a backlash against Angela Merkel’s openness to Middle Eastern refugees. In May, Austria’s Norbert Hofer came within a percentage point of becoming the first far-right leader since World War II to win a national election in Europe. Far-right parties in the Netherlands, Poland, and even the traditionally liberal Northern European countries are enjoying a similar renaissance. The terms “nativism,” “reactionary,” even “fascism” appear in political conversation with increasing regularity. Though few of these leaders profess deep religious commitments, their popularity seems driven in significant part by religious ressentiment — an awareness of the decline of Christian (or “Judeo-Christian”) civilization and a determination to arrest and, if possible, reverse that decline.

Political liberals who long expected to live in an increasingly liberal world may find themselves disoriented by these manifestations, whose nature they are ill prepared to understand, and they certainly wish such “forces of reaction” would just go away. But these forces will not go away. If we were to wish for something less fantastic than the disappearance of our political opposites, we might think along these lines: It would be valuable to have at our disposal some figures equipped for the task of mediation — people who understand the impulses from which these troubling movements arise, who may themselves belong in some sense to the communities driving these movements but are also part of the liberal social order. They should be intellectuals who speak the language of other intellectuals, including the most purely secular, but they should also be fluent in the concepts and practices of faith. Their task would be that of the interpreter, the bridger of cultural gaps; of the mediator, maybe even the reconciler.

Half a century ago, such figures existed in America: serious Christian intellectuals who occupied a prominent place on the national stage. They are gone now. It would be worth our time to inquire why they disappeared, where they went, and whether — should such a thing be thought desirable — they might return.

In the last years of the Weimar Republic, Karl Mannheim, an influential sociologist, argued that a new type of person had recently arisen in the Western world: the intellectual. These were people “whose special task is to provide an interpretation of the world,” to “play the part of watchmen in what otherwise would be a pitch-black night.” Just a few years after writing these words, Mannheim — a Hungarian Jew — was forced out of his university position by the Nazi regime.

Not long after he fled to England, Mannheim began sitting in on a small gathering of highly educated Christians. The group was convened by J. H. Oldham, a missionary and advocate for Christian unity. Oldham’s Moot met several times a year starting in 1938, and was chiefly attended by Christian intellectuals. (T. S. Eliot was among the most active members.) Mannheim was drawn to the Moot because in their discussions he found intellectuals playing their proper role as interpreters and watchmen. As total war drew closer, and then as it unfolded in all its horror, the members of the Moot met to reflect not so much on the defensibility of warfare or its conduct but on the effect that the war was having on British, and to some extent American, society. It was in this sense that the Moot’s participants were watchmen: not Juvenal’s guardians (Quis custodiet ipsos custodes?), or for that matter Alan Moore’s comic-book version, but interested observers whose first job was not to act but to interpret.

Across the Atlantic a similar, though more public and ecumenical, group formed in 1939 through the work of Louis Finkelstein, a rabbi at the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York. This endeavor bore the unwieldy title of the Conference on Science, Philosophy, and Religion in Their Relation to the Democratic Way of Life. It was a more contentious affair than the Moot, largely because of Finkelstein’s determination to gather in a single group scientists and humanists, Christians, Jews, and unbelievers. Jacques Maritain, a French Catholic philosopher then living in exile in New York, warned against such inclusiveness; he believed that only religious thought could adequately counter the moral crisis that was afflicting the democratic West. Though Finkelstein was inclined to agree with his point, he wanted a broader conversation. However, when Mortimer Adler of the University of Chicago made Maritain’s argument openly — adding that the Western world had more to fear from its irreligious professors than from Hitler, which aroused the wrath of Sidney Hook and the other nonbelievers present — the idea of bringing such a diverse group together came to seem unworkable.

Across the Atlantic a similar, though more public and ecumenical, group formed in 1939 through the work of Louis Finkelstein, a rabbi at the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York. This endeavor bore the unwieldy title of the Conference on Science, Philosophy, and Religion in Their Relation to the Democratic Way of Life. It was a more contentious affair than the Moot, largely because of Finkelstein’s determination to gather in a single group scientists and humanists, Christians, Jews, and unbelievers. Jacques Maritain, a French Catholic philosopher then living in exile in New York, warned against such inclusiveness; he believed that only religious thought could adequately counter the moral crisis that was afflicting the democratic West. Though Finkelstein was inclined to agree with his point, he wanted a broader conversation. However, when Mortimer Adler of the University of Chicago made Maritain’s argument openly — adding that the Western world had more to fear from its irreligious professors than from Hitler, which aroused the wrath of Sidney Hook and the other nonbelievers present — the idea of bringing such a diverse group together came to seem unworkable.

Oldham’s Moot and Finkelstein’s Conference shared a pair of beliefs: that the West was suffering a kind of moral crisis, and that a religious interpretation of that crisis was required. The nature of the problem, the believing intellectuals agreed, was a kind of waffling uncertainty about core principles and foundational belief. Faced with ideological challenges from the totalitarian Axis powers and from the communist Soviet Union, democracy did not seem to know why it should be preferred to alternatives whose advocates celebrated them so passionately and reverently. What democracy needed was a metaphysical justification — or, at least, a set of metaphysically grounded reasons for preferring democracy to those great and terrifying rivals.

In was in this context — a democratic West seeking to understand why it was fighting and what it was fighting for — that the Christian intellectual arose. Before World War II there had been Christians who were also intellectuals, but not a whole class of people who understood themselves, and were often understood by others, to be watchmen observing the democratic social order and offering a distinctive interpretation of it. Mannheim, who was born Jewish but professed no religious belief, joined with these people because he saw them pursuing the genuine calling of the intellectual. Perhaps Mortimer Adler felt the same way: it would otherwise be difficult to explain why he, also a Jew by birth and also (at that time) without any explicit religious commitments, would think that the West could be saved only through careful attention to the thought of Thomas Aquinas.

Though the key Christian intellectuals of the day and their fellow travelers — Mannheim and Adler, Eliot and Oldham, W. H. Auden, Reinhold Niebuhr, Dorothy Sayers, and many others — did not oppose their social order, they were far more critical than their predecessors had been during World War I. The Christian intellectuals of World War II found their society shaking at its foundations. They were deeply concerned that even if the Allies won, it would be because of technological and economic, not moral and spiritual, superiority; and if technocrats were deemed responsible for winning the war, then those technocrats would control the postwar world. (It is hard to deny that those Christian intellectuals were, on this point at least, truly prophetic.)

But their voices were heard, throughout the war and for a few years after its conclusion. On both sides of the Atlantic, they published articles in leading newspapers and magazines, and books with major presses; they gave lectures at the major universities; they spoke on the radio. C. S. Lewis and Reinhold Niebuhr (to take just two examples) were famous men — appearing on the cover of Time in 1947 and 1948, respectively.

Though there remain today Christians who are also public intellectuals, their place in society and the Christian faith’s place in their thinking mark them as very different from the figures with whom Karl Mannheim came to associate. If we wish to know why this species became extinct, the short answer is that the Christian intellectual was the product of World War II, and when that war was over, the epiphenomena it had generated simply faded away. But there is also a longer and more complex answer.

This answer will necessarily connect itself to the broader issue of the declining place of Christianity in American life — a subject of evergreen interest, it would seem, especially among Christians. In recent years we have seen Ross Douthat’s Bad Religion: How We Became a Nation of Heretics, Joseph Bottum’s An Anxious Age: The Post-Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of America, and George Marsden’s The Twilight of the American Enlightenment: The 1950s and the Crisis of Liberal Belief. The lack of prominent, intellectually serious Christian political commentators — familiarly known as the “Where Is Our Reinhold Niebuhr?” problem — has frequently been explored since Niebuhr’s death in 1971. But the disappearance of the Christian intellectual is a more curious story, because it isn’t a story of forced marginalization or public rejection at all. The Christian intellectuals chose to disappear.

It was not wholly elective, of course. W. H. Auden, who throughout the war years had emphasized in both poetry and prose the need for a theologically based understanding of the global conflict, visited the Phi Beta Kappa Society at Harvard in 1946 to read “Under Which Lyre,” a poem celebrating the followers of Hermes (the humanists) in their unequal contest against the minions of Apollo (the technocrats). At the time, the president of Harvard was James Bryant Conant, a chemist who had become captivated by the techno-utopian mood of the era. One of the dominant figures of American intellectual culture, Conant had been the chairman of the National Defense Research Committee during World War II, and as such had overseen the Manhattan Project. (He was present at the first atomic-bomb test at Alamogordo, New Mexico, in July 1945.) His experiences in the war years intensified his determination to transform Harvard from a liberal-arts school into America’s leading institution for the study and promotion of science and technology. “When I was delivering my Phi Beta Kappa poem in Cambridge,” Auden later told his friend Alan Ansen, “I met Conant for about five minutes. ‘This is the real enemy,’ I thought to myself. And I’m sure he had the same impression about me.” But it was clear to Auden which of them had the power to impose his vision on America.

Lewis and Niebuhr got their Time covers soon after that, and the magazine also gave Auden’s book-length The Age of Anxiety a reverent review. But within the decade the cultural scene had shifted dramatically. Niebuhr’s place as reliable sage had given way to a very different authority: the scientist. The exemplary figure here was John von Neumann, a central force behind the development of the first powerful computers and the hydrogen bomb — and the author of the first major paper in game theory, from which today’s behavioral economics descends. “I have sometimes wondered whether a brain like von Neumann’s does not indicate a species superior to that of man,” Hans Bethe, who would win the Nobel Prize in Physics, told Life magazine on the occasion of von Neumann’s death in 1957. The same article went on to praise von Neumann as being “more than anyone else responsible for the increased use of electronic ‘brains’ in government and industry.” The full title of Life’s encomium is: “Passing of a Great Mind: John von Neumann, a Brilliant, Jovial Mathematician, Was a Prodigious Servant of Science and His Country.”

The emphasis on von Neumann’s service to his country is noteworthy. Writing about the nature of intellectuals as a group, Karl Mannheim had said that any individual intellectual “takes a part in the mass of mutually conflicting tendencies.” The phrasing is inelegant, but the point clear: the social value of the intellectual derives from his or her acknowledgment of multiple, not always harmonious, allegiances, and potentially competing values. During World War II the ability of Christian intellectuals to provide a perspective different from that of governments was precisely why they were valued. There was a general unease during the early Forties about the possibility of “winning the war but losing the peace” — losing the peace by losing the national soul. (The origin of the phrase is unknown, but Niebuhr favored it highly.) In this context, reminders of “eternal values” were often welcome.

All that changed with the arrival of the Cold War, which, in contrast to the complex, shifting alliances and enmities of the World Wars, was simply and bluntly binary. It was the American-led democratic world, Judeo-Christian at its heart, against totalitarian atheist communism, in a battle to the death. (The term “Judeo-Christian” is almost coterminous with the Cold War, and in the American context is closely associated with Will Herberg’s best-selling Protestant–Catholic–Jew, from 1955.) This was not an environment in which the recognition of “mutually conflicting tendencies” was seen as a virtue; and highbrow Christians, like their lower-browed coreligionists, were generally accepting of this worldview.

Those who still held that democracy was not a self-sustaining enterprise tended to make that point subtly and indirectly, as when Auden, in “Vespers,” his great prose poem of 1954, wrote that “without a cement of blood (it must be human, it must be innocent) no secular wall will safely stand.” It is a poem in which the name of Jesus does not appear (“call him Abel, Remus, whom you will, it is one Sin Offering”). Some of the leading religious cultural critics of the World War II period had shifted their emphases, fallen silent, or lost their hold on the public imagination. Auden had become preoccupied with limning the small cultures of friendship and elaborating a poetic theology of the body, largely setting macropolitical questions aside; C. S. Lewis produced far less social criticism in the 1950s than he had in the previous decade, devoting most of his diminishing energies to fiction. T. S. Eliot wrote a handful of plays but otherwise settled into dignified retirement. Niebuhr’s last significant book was probably The Irony of American History, which was published in 1952. For those religious intellectuals who were not inclined to cheerlead for democracy and “Judeo-Christian values,” a certain privatization of religious experience and discourse was the most likely alternative.

And yet another factor: “anti-intellectualism in American life” — as Richard Hofstadter named the tendency in his book of 1963 — had a profound effect on the preparation of church leaders of all denominations in this country. As anti-intellectualism took a greater hold over American life in general, and over Christian life in America in particular, it came to seem almost unnatural for a congregational minister also to be a deeply learned person, an intellectual with an intellectual’s voice.

To be sure, in America the Fifties were a time of public emergence for many Catholic intellectuals, especially writers of fiction: J. F. Powers, Flannery O’Connor, Walker Percy. But these figures were almost assertively apolitical, and when Catholics did write politically, it was largely in order to emphasize the fundamental compatibility of Catholicism with what John Courtney Murray — a Jesuit theologian who was the most prominent Catholic public intellectual of that time — called “the American Proposition.” Murray was not wholly uncritical of the American social order, but his criticisms were framed with great delicacy: in a time of worldwide conflict, he wrote, “there is no element” of that proposition that escapes being “menaced by active negation, and no thrust of the project that does not meet powerful opposition.” Therefore, “America must be more clearly conscious of what it proposes, more articulate in proposing, more purposeful in the realization of the project proposed.” The American idea is in no sense mistaken, though Americans might need to be “more articulate” in stating and defending that idea. This Murray was willing to help us do, by explaining that the Catholic tradition of natural law was the very same principle that the Founding Fathers appealed to when they declared “that all men are created equal [and] are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights.” It is wholly unaccidental that Murray’s book We Hold These Truths: Catholic Reflections on the American Proposition was published in 1960, when a Roman Catholic named John F. Kennedy was standing as the Democratic Party’s nominee for president of the United States.

The various Christian denominations and traditions, while generally comfortable with the American Proposition, nevertheless devoted considerable resources to building their own institutions. The twenty-five years after the conclusion of World War II saw dramatic growth in Christian publishing houses, magazines, colleges, and universities — Catholic and Protestant alike — in quality as well as numbers. Under the leadership of Theodore Hesburgh, the University of Notre Dame grew from an academically mediocre football powerhouse into a major research university. (When Hesburgh became president, in 1952, the university’s budget for faculty research was $735,000; when he retired, in 1987, it was $15 million.) In 1965, when Jeanne Murray, an English major at the evangelical Wheaton College, in Illinois, won The Atlantic Monthly’s annual undergraduate writing prizes for both poetry and fiction, the college took her success as evidence that a Christian education was compatible with a deep commitment to the liberal arts. That Wheaton, long known primarily as the alma mater of Billy Graham, is today perhaps better known as a repository of the papers of C. S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien testifies to this shifting emphasis.

As these institutions grew stronger and more confident, they provided ways for highly educated Christians, Christians who perhaps in an earlier era would have had a chance of becoming significant public intellectuals, to talk to one another more than to the culture at large. As they devoted themselves to these labors, all around them the Sixties were happening; by the time they realized just how dramatically the culture had changed, it was too late for them to learn its language — or for it to learn theirs.

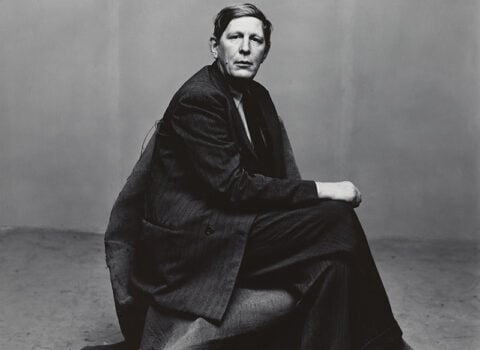

One career might serve to illustrate this general trend: that of Richard John Neuhaus. Neuhaus first made a name for himself in the late Sixties, when he was serving as the pastor of a black Lutheran congregation in Brooklyn. He participated vigorously in the civil-rights movement, and if he later exaggerated his relationship with Martin Luther King Jr., there was indeed something to exaggerate. The practice of social protest led him, quite naturally he believed, to vocal opposition to the Vietnam War. He appeared regularly on television, published widely, and was reported on and interviewed by every major periodical in America. Neuhaus was not a scholar, but he was certainly an intellectual, and was capable of reflecting learnedly on the ways in which Scripture and Christian tradition spoke to the crises of the time. (It is said that when they met, Reinhold Niebuhr remarked, “I’m told you’re the next Reinhold Niebuhr.”)

But then things changed for Neuhaus. He did not cease to think that racism was a massive wound at the heart of American life, nor did he cease to believe that the Vietnam War was utterly misbegotten; but he did come to believe that the liberal establishment was neglecting an equally serious moral issue: abortion. For Neuhaus, it was obvious that the Supreme Court’s Roe v. Wade decision of 1973 was disastrous from the perspective of Christian ethics, and he seems for a time to have expected his fellow antiwar and antiracism Christians to join him in denouncing the verdict. In this expectation he was mistaken, for American culture had divided along fault lines that he had not fully grasped. Those who opposed the war and supported King came also, by and large, to support the sexual revolution, which included among its many aspects support for abortion. Those who opposed abortion — and that coalition was slow in forming: evangelicals took some time to join their Catholic brothers and sisters in protest — did so from a position of moral conservatism, which, it seemed to them, went along with a social and cultural conservatism that made them reluctant to set themselves wholly at odds with the actions of the U.S. government.

Neuhaus found himself increasingly isolated from his former companions in social protest; television programs were less likely to invite him to share his thoughts, and many of the journalistic outlets that had been receptive to him closed their doors. All this led Neuhaus toward a kind of intellectual entrepreneurship that would empower him to pursue the full expression of his social concerns, which he never ceased to believe were consistent and coherent in ways that his former allies on the left failed to recognize. (One of the last articles he wrote, just before his death in 2009, was titled “The Pro-Life Movement as the Politics of the 1960s.”) After a couple of false starts, in 1990 he created the Institute on Religion and Public Life, whose flagship endeavor was the magazine First Things.

The German philosopher Jürgen Habermas is the great theorist and explainer of the public sphere, that conversational space in a society where the issues of the day are debated and contested — where alternative points of view are considered by the public. Nancy Fraser, a feminist political theorist, pointed out that not everyone gets to be a part of this public sphere: women and minorities, especially, tend not to be invited. They are not given space in the newspapers and magazines, or places at the talk-show table. They are therefore driven to create what Fraser called “subaltern counterpublics”: their own publishing houses, magazines, and websites where they can articulate their convictions.

Subaltern counterpublics are essential for those who have never had seats at the table of power, but they can also be immensely appealing to those who feel that their public presence and authority have waned. It is possible that Neuhaus could have worked harder to reclaim a seat at the table — to get, for instance, the same kind of hearing for his pro-life views that he had earlier received for his antiwar and antiracism stances. But Neuhaus, and many who shared his core convictions, made the prudential judgment that this renewed access would be impossible to acquire — and if acquired would come at too high a price. In 1996 Stanley Fish, the literary and legal theorist, put it this way — curiously enough, in the pages of Neuhaus’s First Things:

If you persuade liberalism that its dismissive marginalizing of religious discourse is a violation of its own chief principle, all you will gain is the right to sit down at liberalism’s table where before you were denied an invitation; but it will still be liberalism’s table that you are sitting at, and the etiquette of the conversation will still be hers.

I wrote regularly for First Things in those days, and when Fish submitted his essay to the journal, Father Neuhaus — as he had by then become, having converted to Catholicism in 1990 and been ordained to the priesthood shortly thereafter — asked me whether I thought he should publish it. It made him nervous. The title Fish had given his essay was “Why We Can’t All Just Get Along,” which at that time was an obvious reference to the words of Rodney King, whose beating by members of the Los Angeles Police Department in 1991 had been captured on videotape. When a jury unaccountably found the police officers not guilty of assault, riots erupted in L.A., after which King plaintively asked, “Can we all get along?” Fish not only didn’t believe that we could get along; he didn’t see why religious people would want to:

To put the matter baldly, a person of religious conviction should not want to enter the marketplace of ideas but to shut it down, at least insofar as it presumes to determine matters that he believes have been determined by God and faith. The religious person should not seek an accommodation with liberalism; he should seek to rout it from the field, to extirpate it, root and branch.

This blunt endorsement of confrontation, even if the confrontation was only rhetorical, made Father Neuhaus reluctant to publish the essay.

In the end, he decided to run it, but accompanied by an editorial response. I pleaded with him to allow me to write that response, but he determined to do it himself, and titled his piece “Why We Can Get Along.” It was his conviction that the existence of journals like First Things — and, in other domains of American civic life, religious institutions like the Franciscan University of Steubenville and Wheaton College — made mutual tolerance if not possible then at least significantly easier. Accommodation had been purchased at the price of creating domains that were separate but, in theory at least, equal.

What about those Christian thinkers who have chosen a path that disdains separatism? They, too, have been faced with limited choices, narrow avenues of thought and influence — but very different ones.

Take Cornel West, who has long striven to articulate a prophetic Christian witness — this is his consistent self-description — both to the academy and to the public at large. But after lengthy stints at Harvard and Princeton, he has recently moved to Union Theological Seminary in New York City. (It is perhaps not wholly coincidental that Union was the longtime employer of Reinhold Niebuhr.) The question for West, and I think for many Christian intellectuals today, is one of social and institutional location. From what place is one best suited to bear witness to what one believes to be core Christian truths, in a manner that is both free and audible?

West has been noted in recent years for his increasingly fierce denunciations of a man he once lavished with great praise: Barack Obama. In 2014 West said that the president “posed as a progressive and turned out to be counterfeit. We ended up with a Wall Street presidency, a drone presidency, a national security presidency”; more recent comments make this criticism seem mild. This is perhaps the rage of a Christian prophet who never expected to be heeded by the public at large but who cannot reconcile himself to what he believes to be the betrayal of foundational social commitments by a person whom he had considered a “companion and colleague.”

It will be said that West has exiled himself from a strong public presence by his political “extremism,” but extremism is intrinsic to the prophetic calling, as Martin Luther King Jr. commented long ago in his “Letter from Birmingham Jail.” The problem for West is that he is ignored by, as it were, both sides of his inheritance: a man who would be president cannot endorse West’s radical politics, while West’s Christianity, and that of his forebears in the civil-rights movement, is irrelevant or even counterproductive to today’s black activists. When Ta-Nehisi Coates writes to his son, “You must resist the common urge toward the comforting narrative of divine law, toward fairy tales that imply some irrepressible justice,” he is quite explicitly rejecting King’s Christian faith and his famous claim that “the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice.”

In any case, it cannot be surprising that Obama’s favorite Christian intellectual is not West but a gentler figure, the novelist Marilynne Robinson. Last June, when the president delivered the eulogy for Clementa Pinckney, the murdered pastor of Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina, he said, “That’s what I felt this week — an open heart. . . . It’s what a friend of mine, the writer Marilynne Robinson, calls ‘that reservoir of goodness beyond and of another kind.’ ”

In light of the history I have been narrating here, the career of Marilynne Robinson looks like a case of opportunities taken, but also opportunities missed. It is true that, especially in her fiction, she offers to a (largely secular) audience a picture of what the world looks like when it is irradiated by faith or the possibility of faith; but it is never a faith that calls upon her readers to act differently, socially or politically or morally, than they would normally be inclined to act. In her essays, she often speaks explicitly as a Christian, but there tends to be a strange mismatch between her subject and her audience. Take “Fear,” an essay from 2015 in which she writes that “contemporary America is full of fear” — a fear manifested largely through a kind of cult of firearm ownership — and “fear is not a Christian habit of mind.” If Robinson wants to persuade her fellow American Christians to reject the culture of guns and overcome their fear, The New York Review of Books is an odd place to do it. My point is not that Robinson’s argument is wrong but that it offers a highly critical interpretation of people who are not reading it, and leaves the core assumptions of its audience unchallenged.

In another recent essay, “Memory,” she writes,

I am a Christian. There are any number of things a statement of this kind might mean and not mean, the tradition and its history being so complex. To my utter chagrin, at this moment in America it can be taken to mean that I look favorably on the death penalty, that I object to food stamps or Medicaid, that I expect marriage equality to unknit the social fabric and bring down wrath, even that I believe Christianity itself to be imperiled by a sinister media cabal. It pains me to have to say in many settings that these are all things I object to strenuously on religious grounds, having read those Gospels.

There is, it seems to me, a good deal to find fault with here: the apparent implication that, since Robinson says she holds the views she does simply by virtue of having read the Gospels, those Christians who see things differently than she does have not read the Gospels; or the notion that such reading could settle practical questions of social policy; or the notion that she “has to” distance herself from other Christians who do not share her political and social views.

That last point above all. For when we read the great Christian intellectuals of even the recent past we notice how rarely they distance themselves from ordinary believers, even though they could not have helped knowing that many of those people were ignorant or ungenerous or both. They seem to have accepted affiliation with such unpleasant people as a price one had to pay for Christian belonging; Robinson, by contrast, seems to take pains to assure her liberal and secular readers that she is one of them. (From the same essay: “I have other loyalties that are important to me, to secularism, for example.”)

Something similar might be said of Robinson’s recent conversation, also published in The New York Review of Books, with Obama, to whom she returns the name of friend. It may be poor form to use a conversation with a friend in order to speak truth to power, but I for one would have appreciated a dose of Cornel West–like poor form. After all, the claim that “contemporary America is full of fear” might also be applied to the person who promised but failed to close the prison at Guantánamo Bay. I think Robinson may well be the finest living American novelist, and at her best a brilliant essayist, but whatever her religious beliefs, her culture seems to be fully that of the liberal secular world — and it may matter, in this regard, that her professional career has been at a public university. While surely she must know some living Christian subculture from the inside, she does not seem to be interested in representing its virtues, or its mixture of virtues and vices, to an unbelieving world, or to speak on its behalf, or to speak to it in any general way.

I fear that this sounds like a reproach, though I mean for it to be a lament. Blame is hard to assign here. If we cannot imagine Robinson being invited to preach at a big-box Bible church somewhere in suburbia, that may say less about her than about the anti-intellectual and artistically indifferent culture of much of today’s evangelicalism; but then, those developments may have been exacerbated by Christian intellectuals’ neglect of their responsibilities to the life of their churches. At some point in the past sixty years or so a perverse and destructive feedback loop engaged, and I cannot see how to disengage it.

Still, it is noteworthy how consistently inward and solitary the faith of the characters in Robinson’s novels is, including that of her most compelling creation, the elderly pastor John Ames in Gilead. The community of church is not a strong element in these people’s lives; they tend not to speak for anyone or anything more than themselves, and the conversations that they have about faith are mostly internal. I can’t help wishing that someone, someone of Marilynne Robinson’s stature and gifts, would tell readers of The New York Review of Books that such church communities need not be scorned or feared, and then tell those church communities the same about the readers of The New York Review of Books. That would require a patience, a kindness, a courage that it seems scarcely possible to ask for in our current climate.

Christians in public institutions are legally constrained in their speech. As Stanley Fish once shrewdly commented,

What, after all, is the difference between a sectarian school which disallows challenges to the divinity of Christ and a so-called nonideological school which disallows discussion of the same question? In both contexts something goes without saying and something else cannot be said (Christ is not God or he is). There is of course a difference, not however between a closed environment and an open one but between environments that are differently closed.

In institutions of the public sphere that have no connection to the state, such as the New York Times, there is legal freedom, but that institution might not wish to sully its good name, or alienate its base, by providing a platform to overly sectarian voices.

When Cornel West moved to Union Theological Seminary, he was making a move not only to Manhattan — still the media heart of America — but also to a church-based institution, a seminary, a place of training for the ministry as opposed to preparation for a career on Wall Street. For Reinhold Niebuhr, there was no real problem of this kind: it was not necessary for him to choose between being free and being audible. He could teach at Union Seminary, write for every major periodical in America, have his books published by a venerable New York house (Scribner); whatever conflicts he may have experienced in his career he did not experience as Christian intellectuals do today.

It was the Sixties that changed everything, and not primarily because of the Vietnam War or the cause of civil rights. There were many Christians on both sides of those divides. The primary conflict was over the sexual revolution and the changes in the American legal system that accompanied it: changes in divorce law, for instance, but especially in abortion law. (Many Christians supported and continue to support abortion rights, of course; but abortion is rarely if ever the central, faith-defining issue for them that it often is for those in the pro-life camp.) By the time these changes happened and Christian intellectuals found themselves suddenly outside the circles of power, no longer at the head table of liberalism, Christians had built up sufficient institutional stability and financial resourcefulness to be able to create their own subaltern counterpublics. And this temptation proved irresistible. As Marilynne Robinson has rightly said in reflecting on the agitation she can create by calling herself a Christian, “This is a gauge of the degree to which the right has colonized the word and also of the degree to which the center and left have capitulated, have surrendered the word and also the identity.”

There is surely no neat solution to the dilemmas that Christian intellectuals began to face in the Sixties and still face today, and perhaps no solution at all. I speak as one of these Christian intellectuals, at least I flatter myself to think so, though I have never wished for or imagined I could achieve a public role like the one occupied by the Niebuhrs and Eliots of an earlier time. I am far too small for that, and disinclined to talking before audiences. Moreover, I have always been haunted by something I once heard the political theorist Jean Bethke Elshtain say: The problem with becoming a public intellectual is that over time you grow more and more public but less and less intellectual. But I have felt for my entire career the difficulties of deciding where to speak and how. About a decade into my professional life it suddenly dawned on me that, unlike the people I went to graduate school with and the professors I saw as my mentors and models, I was never going to have a single audience. It would be necessary for me at times to speak to the church; at other times to believers from other religious traditions; at other times to my fellow academics; and at yet other times to the American public at large. This meant that I would not be able to formulate a single writerly voice, a single mode of articulation, a single rhetoric that I could deploy in any and all situations. Rather I would have to strive to be, as the Apostle Paul said, all things to all people, however disorienting and puzzling that obligation might be.

The model of separate-but-equal domains that Father Neuhaus chose may be the best that is generally available for most Christian intellectuals, but it means that the larger public sphere, the realm of American civic discourse, is deprived of Christian voices that could speak in serious and significant ways of the issues that face us as a country and a society — including the rise of illiberal and confrontational movements that often seem to be rooted in religious identity. Since almost nobody who comfortably belongs to that larger public sphere is interested in anything that Christians or other religious believers have to say — I once heard the philosopher Richard Rorty comment, “Of course the theists can talk, but we don’t have to listen” — it’s unlikely that many will feel it as a loss.

In a more generous mood, late in his life, Rorty borrowed a phrase from Max Weber and referred to himself as “religiously unmusical,” someone who was unable to hear the thoughts and practices of religion as music rather than merely as noise. I say that a more generous mood promoted this formulation because it allows for the possibility that what religious people — and Rorty was referring primarily to religious intellectuals — are saying actually can be music: utterance with meaningful structure, thoughtful organization, and perhaps even beauty. But whether that is or is not the case, Rorty — the grandson of a well-regarded Protestant theologian, Walter Rauschenbusch — confessed himself simply incapable of hearing it as such. I think that, from the Fifties to the Seventies, American intellectuals as a group lost the ability to hear the music of religious thought and practice. And surely that happened at least in part because we Christian intellectuals ceased to play it for them.