One night last April, I walked from my house in Gainesville, Florida, to the Matheson Museum, a shy brick building hidden by a thicket of palmettos and so small that the forty or so people seated inside seemed to make the walls bulge. I’d come for one of the first events in “The Year of The Yearling,” the seventy-fifth-anniversary celebration of Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings’s 1938 novel. Someone had made molasses cookies from a recipe in Marjorie’s cookbook, Cross Creek Cookery, which powered us through a slide show: the backwoods Florida crackers who inspired The Yearling, the map of the scrub annotated in Marjorie’s hand, the writer in sundry poses.

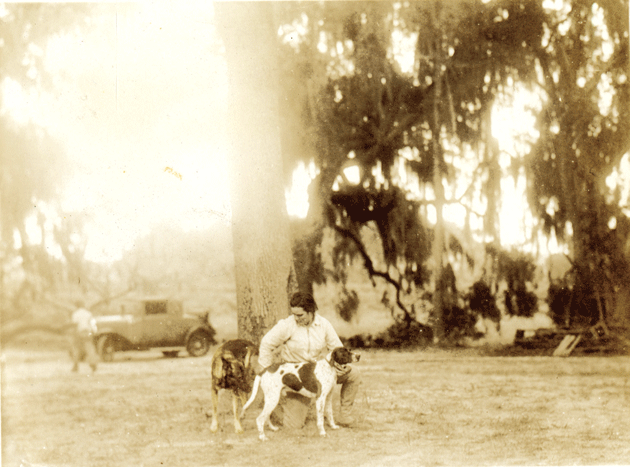

Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings at Cross Creek, photographer unknown. Courtesy Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings Papers, Department of Special and Area Studies Collections, George A. Smathers Libraries, University of Florida

A woman as stout and dark as Marjorie stood before us in a boxy 1940s skirt suit, with a felt hat cocked to the side. This was Betty Jean Steinshouer, a scholar and Chautauqua performer steeped in Marjorie lore. She pulled out a flask and channeled the saucy, blasphemous, drunken writer for more than half an hour. A discussion of Marjorie walling up her barrels of moonshine to keep them away from her maid begot a more general consideration of Marjorie’s dipsomania, which begot the story of her meeting with Ernest Hemingway in Bimini, which begot a meditation on Wallace Stevens, who came to dinner at Marjorie’s and offended her so much that she jotted on his thank-you note:

From Wallace Stevens who spent an evening at Cross Creek being disagreeable and obstreperous. Got drunk, read his poems with deliberate stupidity. Held out his arms to me and said, “Come, my Love.”

The others at the Matheson gobbled all this up, save one white-bearded man who was snoring. During the question-and-answer session, a woman with cropped silver hair stood and spoke mistily and at length about her first time reading The Yearling, and a man apostrophized the taxidermied bear in the corner of the room, calling him Slewfoot, the name of the canny black bear that is the family’s nemesis in the book. Then we were released, and I made the walk home in the dark, our neighborhood hoot-owl flapping from oak to oak beside me. I found I was terribly sad.

The Yearling was awarded the Pulitzer Prize. It was the best-selling novel of 1938, and it has sold millions of copies since. The book remains familiar in a vague way to many American adults, who probably read it in school or have seen the 1946 film based on it. But it is more than a bestseller, and certainly more than a dated children’s book. It is a genuine classic, influenced by Hemingway’s declarative simplicity and edited by Hemingway’s legendary editor, Maxwell Perkins. For a time, its author was a literary figure to rival the rest of Perkins’s stable, which included F. Scott Fitzgerald and Thomas Wolfe. Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings was friends with Zora Neale Hurston, Martha Gellhorn, and Robert Frost. She corresponded with John Steinbeck, Thornton Wilder, and Eleanor Roosevelt. She was Margaret Mitchell’s guest at the Atlanta premiere of Gone with the Wind. Her house in Cross Creek, about twenty miles from Gainesville, is a state park.

And here’s what “The Year of The Yearling” will have given us by the time it wraps up in March: presentations on pets and pet care and the plants and seasons in the book, tastings of cracker foods, a number of walks and runs (such as the 5K Yearling Run and Scamper at M. K. Rawlings Elementary School), and various static exhibitions. There is little to entice people not already fond of the book, and even less serious discussion of its literary merits. It seems as if the organizers, though they planned with great goodwill, forgot to pitch the novel to anyone outside their circle.

At the Matheson, we’d been throwing confetti and dancing the schottische, all the while ignoring the water lapping at our ankles. Despite the torchbearers and the molasses-mouthed fans, The Yearling is slowly sinking into obscurity. The novel sold about 6,000 copies in all formats in 2012, which represents a typical week for The Great Gatsby, To Kill a Mockingbird, or The Catcher in the Rye, if we count only the most popular of the many published editions of these books. When I asked Scribner what they were doing to celebrate the anniversary, I was told there was an illustrated edition being published in the fall by Atheneum, the house’s children’s division.

The Yearling is a magnificent, transparent, slow-moving river. Its style is direct and free of fireworks, its subjects planted at the beginnings of the sentences, solid as potatoes. The first chapter opens:

A column of smoke rose thin and straight from the cabin chimney. The smoke was blue where it left the red of the clay. It trailed into the blue of the April sky and was no longer blue but gray. The boy Jody watched it, speculating.

Like so it runs, for about 400 pages.

* A note on the term “cracker”: though it seems pejorative, it is simply what the backcountry white settlers who came from Georgia or Alabama called themselves. Nobody knows how the name arose — perhaps as a bastardization of “Quaker,” or as a reference to the bullwhips they cracked when herding cattle or the corn they cracked to make cereal, or from some name the Seminoles bestowed on them (which probably was, come to think of it, pejorative).

The cast is small, mainly keeping to a family of three crackers in the Florida scrub in the early 1870s.* They are Ezra “Penny” Baxter, a diminutive and gentle-hearted man; his wife, Ora, who has given birth to so many babies who died that she has almost no tenderness left in her; and their surviving son, Jody, who is between childhood and adulthood. Jody is dreamy and lonely. He has two friends: his father, and an addlepated, crippled boy nicknamed Fodder-wing. The Baxters live in the Big Scrub, a sandy triangle of land between the St. John’s River to the east, Gainesville to the northwest, and Ocala to the west. The Big Scrub is now the Ocala National Forest: there is a Yearling Trail one can hike, and the feel of the place is that of lurking danger and almost shocking beauty. There are sinkholes and springs and long swaths of spiny, lush foliage. The Yearling expresses both danger and beauty: the Baxters are surviving on the brink, one dead sow or ruined corn crop from starvation, but there are also glorious passages about the land, and hunting scenes that can get even my vegetarian-pacifist blood all het up.

The plot arrives a third of the way into the book, when Penny is bitten by a rattlesnake and almost dies. Struggling, in pain, he shoots a doe that has just fawned in order to draw the venom out of his arm and into the liver he cuts out of her. Penny survives, and Jody returns to rescue the half-starved fawn. Lonely as Jody is, he persuades his parents to make a pet of it and names it Flag. The deer becomes a playful, loyal makeshift brother to the boy. But when Flag becomes a yearling, his wildness kicks in and he endangers the family. Poor Jody is ordered to kill Flag. In one of the most heartrending scenes in American literature, Jody does, but then he runs away in fury and almost starves to death. He returns home unutterably diminished, but finally a man. As with so many great books, a summary of The Yearling makes it seem a bit silly. The novel’s power is subtle, accumulating with every description of the natural world, until the book’s rhythms become almost transcendental.

It seems odd that a novel so sensitive to Florida’s natural environment was written by a carpetbagging Yankee, at least until you remember that most people who live in Florida were not born there. Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings didn’t visit Florida until she was thirty-one, a married woman, and a largely unsuccessful writer. She had been a journalist for the Louisville, Kentucky, Courier-Journal and the Rochester, New York, Times-Union, where she wrote Songs of the Housewife, a daily syndicated verse series. Marjorie’s poems are, I’m afraid, sheer doggerel. Some of them end in exclamation points, and they bear titles such as “Nose News,” “The Jolly Tramp,” “Other Women’s Babies,” “Itching for a Spanking.” There is also the pie cycle: “Good Pie,” “A Very Useful Pie,” “Lemon Pie,” “Cherry Pie,” and the alarming “Ancestral Pies.” The first stanza of the first poem she published, on May 24, 1926, goes:

I call them twice to breakfast —

Then, if they are not there,

I let the smell of sausage

Waft up the kitchen stair.

In March 1928, Marjorie and her first husband, Charles, visited Florida for the first time. She was gobsmacked by the beauty of the state, and late that summer, they bought an orange grove in Cross Creek, thinking that citrus cultivation would give them enough income and leisure to write. By November, they had seventy-four acres with more than 3,000 bearing citrus trees, an eight-room farmhouse, a barn, a tenant house, 200 chickens, two mules, and a Ford truck. Cross Creek was the northernmost frontier of citrus cultivation, and the Rawlingses wouldn’t have been able to keep the trees alive had the farm not sat on the narrow peninsula between Lakes Orange and Lachloosa, which softened the climate. Farming was terrifically hard work, especially at the beginning, and the Rawlingses had to battle freezes and droughts and malaria and the Mediterranean fruit fly, a pest so frightening and pervasive that for a while it seemed the state’s entire agricultural industry would collapse from it. This was pre-DDT and pre-AC. Still, Marjorie loved the place. In Cross Creek, her 1942 essay collection, she writes, of the grove and old farmhouse, “after long years of spiritual homelessness, of nostalgia, here is that mystic loveliness of childhood again. Here is home. An old thread, long tangled, comes straight again.”

She also found herself falling in love with the people around her. Her first notable literary effort, “Cracker Chidlings,” is what one would fear from a Northerner who’d come south to write — a condescending piece of essayese based on what she saw of the illiterate, hookwormy people around her. But the next few years saw some of her most sympathetic and accomplished work: her two best short stories, “Jacob’s Ladder” and “Gal Young ’Un,” the latter of which won the 1933 O. Henry Award, and her 1933 novel South Moon Under, a brilliant and strange vision of contemporary cracker culture.

In November 1933, Marjorie and Charles divorced. She stayed on the farm with a succession of hands and maids to help. Also in 1933, Maxwell Perkins first planted the seed of The Yearling in Marjorie’s brain, writing,

I was simply going to suggest that you do a book about a child in the scrub, which would be designed for what we have to call younger readers. . . . If you wrote about a child’s life, either a girl or a boy, or both, it would certainly be a fine publication, and such books have a way of outdoing even the most successful novels in the long run, though they do not sell many in a given season except now and then.

This was three years before Marjorie began to write The Yearling, and at the time she was still struggling to finish her (terrible) second novel, Golden Apples. She thought, perhaps reasonably, that writing for children would prevent her from being taken seriously. Eventually she concluded that The Yearling would “not be a story for boys, though some of them might enjoy it. It will be a story about a boy — a brief and tragic idyll of boyhood.” With this in mind, Marjorie went bear hunting out in the backcountry with a friend named Barney Dillard and stayed with another friend, Cal Long, in the Big Scrub. She sent Perkins the completed draft on December 2, 1937, and he published it an astonishingly swift four months later, in April 1938.

Massive bestseller, Pulitzer, huge movie deal, Book-of-the-Month Club (the Oprah’s Book Club of the era), on and on. After her years of disappointment, Marjorie was at last hefted to the stars. Except she wasn’t. The struggle continued. She almost died from diverticulitis, an inflammation of the colon, and the disease dogged her for the rest of her life. She developed alcoholism. She abandoned the plans for her next novel, based on the life of Zephaniah Kingsley, an early-nineteenth-century Florida planter. She wrote When the Whippoorwill, a story collection, which is good but not great. She wrote Cross Creek, which some people have tried to persuade me is great but isn’t, fatally marred as it is by racism. She became distracted by love and married Norton Baskin, who owned the Castle Warden hotel in St. Augustine, where a Ripley’s Believe It or Not! museum stands today. With the help of her maid, Idella Parker, she produced Cross Creek Cookery, which offers standard 1940s fare (Egg Croquettes, Lobster Thermidor, Tomato Aspic and Artichoke, Baba au Rhum) mixed with some eccentric Florida dishes (Minorcan Gopher Stew, Coot Surprise, Swamp Cabbage, Chayotes au Gratin, Loquat Preserves). She became involved in the 1946 film adaptation of The Yearling, starring Gregory Peck and Jane Wyman. A former friend, Zelma Cason, sued her for libel over this description in Cross Creek:

Zelma is an ageless spinster resembling an angry and efficient canary. She manages her orange grove and as much of the village and county as needs management or will submit to it. I cannot decide whether she should have been a man or a mother.

The lawsuit soured Marjorie. She bought houses in Crescent Beach, just south of St. Augustine, and Van Hornesville, in upstate New York. Max Perkins died in 1947, breaking her heart; her heart suffered more literal damage in February 1952, when she had a coronary-artery spasm. In 1953, her fourth novel, The Sojourner, which she had labored over for ten years, was published to a critical whisper. She died on December 14, 1953, of a cerebral hemorrhage, and was buried in Antioch Cemetery, near her home in Cross Creek. Norton had discovered it was the wrong cemetery at the last minute, but Marjorie was buried there anyway, because he didn’t want to bother folks by shifting her to the right place. If photographs from the Sun City newspaper are any indication, there were many flowers but few mourners.

These past few months, I haven’t been able to stop wondering what happened to Marjorie and The Yearling. How does a classic run out of steam?

The first person I asked that question was my father-in-law, Clayton, who was born in Gainesville. He was once a boy like Jody, growing up in an alien Florida without air-conditioning or theme parks, and he may be one of the few living people who remembers meeting Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings in person. Clayton was a trial of a child, and to keep him safe in public places his mother put him in a dog harness. Par for the course at Disney World these days, but back then it was horrifying. This was about 1947; Clayton would have been five or so. He and his mother were at the Piggly Wiggly downtown. She’d forgotten the harness, and he was raising sheer hell. Suddenly a vast and angry woman loomed over him, bellowing at his mother, “Can’t you control that child?” Clayton’s parents owned a bookstore; his mother knew that this was the famous writer from Cross Creek, and she was mortified.

I took Clayton to lunch at The Yearling, a restaurant half a mile down the road from Marjorie’s house, where a man named Willie Green played the blues and our server had never read a word of Marjorie’s work. I’d heard the best thing on the menu was the venison.

Clayton and I have a rocky relationship, partially because I blame him indirectly for giving my husband the family business and thereby making me live in Florida, partially because he doesn’t relish my personality. He is also now mostly deaf, and my voice is pitched where it is hardest for him to hear. He answered my question by leaning forward and talking earnestly about how nobody in Florida reads books, and when he was growing up nobody read The Yearling, it just wasn’t important to the culture. He, who as a kid read a book and a half a week, never read it until he was an adult. It’s not surprising that a book about Florida won’t be read by people who don’t read books, and the book is so profoundly about Florida that if people in Florida don’t read it, who else is going to?

People in Florida do read, but I think he touched on something important: there is an internalized scorn of Florida shared by natives like Clayton and people from other states. Why read about Florida? What is Florida? As my neighbor, Jack Davis — a history professor at the University of Florida — puts it, Florida is a “fantasy state and schizophrenic, not knowing whether it’s Northern or Southern so it’s nothing . . . It just doesn’t fit in the national narrative, not as any kind of indelible regional state, so it can’t sustain a book written in a Southern setting. People visit Florida or they relocate to Florida, but it is never home; Ohio or Illinois remains home.”

Florida is the state where grown women impersonate mermaids for a living, where a family of egomaniacs is trying to build the nation’s largest private home (they’re calling it Versailles). Florida is where an armed adult can stand his ground before an unarmed teenager. Because nobody can understand what is happening in this state, Florida has become the butt of a million jokes. Even its shape is suspect: Florida, the dong of America.

Because she concentrated her work in Florida, Marjorie is seen as a regionalist. In this country, literary tastemaking begins in New York City, and regionalists can appear diminished by sticking to one place that is perceived to be less important. Marjorie is unlucky in that her finest work is Florida-based. Florence Turcotte, the archivist in charge of the Rawlings papers at the University of Florida, told me she believes that Marjorie would have broken out of her regionalist reputation had she lived longer. I’m not convinced: Marjorie’s attempts at depicting other places weren’t that good. Something about Florida sparked her alive.

Another factor in the fading of The Yearling may be Marjorie herself. She was not sexy. Though her stamp prettifies her, elongating her neck until it hilariously echoes that of the fawn in the background, she was matronly and angry-looking in life. She was not part of a school or a group — there was no Bloomsbury in Cross Creek — and at a time when Virginia Woolf and James Joyce were publishing their work, Marjorie was a writer of homespun people and straightforward realism. She did not have a spectacular death by suicide, just a brokenhearted, alcoholic one.

She had no advanced politics: she wasn’t a communist, a feminist, or in the avant-garde. The most progressive thing she did was allow Zora Neale Hurston to stay in her main house rather than the maid’s quarters. Of all the Southern states subjected to Reconstruction, Florida experienced the most racial violence. A black man was at greater risk of being lynched there than in Mississippi or Alabama. These were tensions Marjorie ignored in her work, even if she couldn’t in her daily life. The word “nigger” appears several times in The Yearling — and not counterbalanced, as in The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, by any overarching social commentary. Gary Mormino, a professor emeritus of history at USF St. Petersburg, says he nominated the book for the Tampa library system’s “One Book, One Community” program, but that it was shot down because of its use of the word.

It also doesn’t help that The Yearling is Marjorie’s only first-class book. South Moon Under, her début novel, is full of intelligence and empathy, but its scope is small: it makes no swaggering claims. One classic book, two good ones, two terrible ones (not including the posthumous ones, which probably shouldn’t have been published): this is a small, savory mouthful for a scholar hoping to dine on a subject for a whole career.

Worst of all, practically everyone I spoke to noted that The Yearling is considered a book for young readers. It is therefore shunted into a category beneath the regard of serious adults. It hadn’t initially occurred to me that this could be a factor, primarily because I first read it as an adult and it was given the Pulitzer, which is not an award for children’s books. I suppose some consider it to be a young-adult book because it’s a bildungsroman drawn in sharp primary colors, written in accessible language, and bearing only faint traces of sex or humor.

I talked to Carolyn Harrell, a teacher at P. K. Yonge Development Research School, in Gainesville. She has been teaching for forty-eight years, which I found impossible because she looks barely sixty, with soft white hair and an unlined face. The kids who get Harrell are lucky: she speaks with such tremendous energy that she’d make chalk seem thrilling. Harrell is a Gainesville native and, like my father-in-law, didn’t read The Yearling until she was an adult. She teaches it in phases over sixth, seventh, and eighth grades, supplementing readings with a visit to Marjorie’s house, a hike through Ocala National Forest, and a feast based on Cross Creek Cookery. In all her years of teaching in Gainesville, so close to the place and history described in the book, she has never come across another teacher who has taught The Yearling.

She told me too that her students often have difficulty with the book. It is long, which is off-putting. There’s so much description. The plot is slow. Children are reading less, and the statewide curriculum is going in the direction of short and dry pieces. Without Harrell there to push them, most of her students wouldn’t read it. When her students do read on their own, they read fantasy, books about vampires and werewolves and other supernatural creatures. The average child who picked up The Yearling when it was released, during the Great Depression, would have heard the book speaking directly to him, in his world not unlike Jody’s, with hunger and poverty all around. There may be hunger in the lives of potential young readers now, but it is different: few children would know what to do with a gun if a bear charged at them out of the dark woods, let alone how to feed their families in the wilderness.

Finally, The Yearling reflects a world we’re losing, and does so in an orgy of carnage. Among the things killed and (mostly) eaten in the book are alligators, rabbits, deer, raccoons, squirrels, gopher tortoises (threatened), bass, bream, turkeys, foxes, possums, rattlesnakes, black bears (threatened), lynxes (endangered), panthers (endangered), curlews (endangered), and the last great wolf pack east of the Mississippi (critically endangered). Marjorie wrote of one of the final American frontiers, where nature hadn’t yet been swallowed by civilization, but she came at it with sympathy for the killers, the people who slaughter the beasts in order to survive, and these days that feels wrong-sided. Steven Noll, another UF historian, told me that the history of Florida is a battle against water up until 1970, with dredging and drying up the Everglades and handling mosquitoes and humidity; since then, the battle has been to keep the water we have. By 1990, Florida had wiped out 46 percent of its wetlands, and the flora and fauna of the state suffered catastrophically. The aquifer is diminishing at an alarming rate, though the politicians in Tallahassee don’t seem to be noticing. The more we pump, the more brittle the limestone layer between the aquifer and the surface becomes, leading to more sinkholes. The more we deplete the freshwater aquifer, the more the salt water of the ocean will intrude, hastened by rising sea levels. Once polluted by salt water, freshwater deposits are gone forever. The state of Florida will no longer be able to support its agriculture, its tourism economy, or its population of 19.3 million.

At The Yearling restaurant, my father-in-law spoke of climate change, but in personal terms. When he was a boy, the wildlife was far denser, he said. He collected snakes in his back yard; he saw raccoons and possums every day. He sees such animals rarely now. In the summer, there were daily microstorms that would blow through and cool the world off in a burst of rain. These, too, are gone.

“So The Yearling is, to you, a picture of a lost Florida,” I said.

“A lost Florida,” Clayton said. And this dry former statistician, whom I’d never seen show much emotion at weddings or births of grandchildren, put a hand to his mouth and cried.

Here’s where I declare my own allegiance: I love Marjorie. I love Marjorie because of The Yearling, but also because our places coincide, and place is at the root of everything I’ve ever written. During my first difficult years of being a settler in Florida, I turned to The Yearling in hopes that it would teach me how to love this messy state. Like most people who read the book as an adult, I was expecting a children’s book, and so was stunned to awe by The Yearling’s beauty and strength and by Marjorie’s empathy for her poor and struggling characters. Later, when I looked into Marjorie’s life, the coincidences felt uncanny: I’ve also lived in Louisville and in Madison, Wisconsin, and my husband’s family has a place on Crescent Beach. Van Hornesville, where Marjorie owned her last house, is fifteen miles from Cooperstown, where I was born and raised; my mother taught biology at Van Hornesville’s high school. But Marjorie found a way to let Florida bloom into something magnificent inside of her. I am still struggling to do so.

It is hard to be a person in love with The Yearling and the stunning landscape it evokes and not mourn their simultaneous passing. It feels inevitable that The Yearling will continue to lose its audience, that the state will continue to lose its native wildlife, that other species will continue to invade. The last time I went out to Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings’s house in Cross Creek, Orange Lake was almost entirely dried up, and the little water I saw was covered in hyacinths. On the way there, we passed a smashed armadillo on the side of the road and our hood was stippled in lovebugs, swarms of insects that fly around twice a year coupled at the genitals. An introduced insect called the Asian citrus psyllid, which causes citrus greening (also called huanglongbing), is rapidly killing off the state’s crops. Armadillos and lovebugs are both invasive species that Marjorie would have been bewildered to see.

If there’s solace here, it’s in the knowledge that not all change is to be regretted. A Gainesville-area boy was bitten by a rattlesnake in May, but these days we have ambulances and doctors who are not hopeless drunks. Unlike Penny, the boy didn’t have to kill a postpartum doe: eighty vials of antivenin later, he walked out of the hospital with the makings of a brand-new diamondback wallet. Every spring, thousands of new Flags are born; with the predators of Florida pretty much wiped out, the deer population is almost unmanageably large. Perhaps after Florida’s aquifer is salinated and the state is rendered mostly unlivable, those who choose to remain will be the kind of gun-loving, off-grid survivalists to whom The Yearling’s own gun-loving, off-grid survivalists will speak loudly and beautifully.

It is also true that only a lucky writer can write a classic, and it’s only a rare classic that can be perennially relevant. If a book we love doesn’t survive, it is maybe not the fault of the reader or the author or the book, but just that the world began spinning at a different speed than the book could keep up with. Someone is now writing the next blazing work that will inflame us all and then quietly and surely burn itself out. How glorious it will be for the short time it is alight, how much some lonely, struggling soul will need it. How bearable it will make living in the world.