If ever there was a person born to end up in a Russian prison, it was Dima Litvinov. The grandson of one of the most eloquent writers to emerge from Stalin’s gulag, and the adopted son of a dissident, he got his first taste of the Soviet penal system when he was six years old. In 1968, his stepfather was exiled to Siberia. Litvinov joined him there, spending the next several years in a remote mining village.

The family returned to Moscow in 1972 and was soon forced to emigrate to the United States. Here Litvinov grew up, got a master’s in anthropology, and eventually landed a job with Greenpeace. In 1990, he joined the crew of a Greenpeace ship sailing to the Arctic to protest the continuation of nuclear testing near the Russian archipelago of Novaya Zemlya. The ship was seized by the Russian Border Guard as it approached Murmansk. Litvinov’s grandfather, Lev Kopelev, then living in Germany, told journalists the boy was maintaining a proud family tradition: he was the third generation to go to jail for a good cause.

As it happened, Litvinov and his shipmates did not go to jail. The matter was resolved quickly, following a burst of international protest, and everyone was released to a triumphant round of handshakes and media interviews. This is how it usually works with Greenpeace. There are, of course, exceptions: in 1985, French intelligence bombed and sank the organization’s flagship, Rainbow Warrior, while it was docked in Auckland, New Zealand. One crew member died. Yet the ship’s captain, an American named Peter Willcox, recently told me that he had been more energized than traumatized by the attack: “A bunch of hippies in an old boat had scared a First World government so much they wanted to bomb us.”

Willcox went right back out to sea for Greenpeace, and for nearly three decades the worst thing he suffered in this line of work was his disappointment at failing to get the environment cleaned up as efficiently as possible. Then, last September, the organization’s Arctic Sunrise was seized off Murmansk. All thirty people aboard, including Litvinov and Captain Willcox, were detained. This time, the initial wave of international protest did not dislodge the team from custody. Instead they were dispersed to an assortment of chilly cells and threatened with sentences of up to fifteen years.

And there they might have remained, had it not been for the Sochi Olympics. Vladimir Putin, seldom one to fret over bad publicity, was uncharacteristically eager to clean up Russia’s image in advance of the games. At his behest, a parliamentary amnesty was declared and all charges against the so-called Arctic 30 dropped. On December 27, more than three months after the ship was seized, Litvinov returned home to Stockholm, Willcox headed for Maine, and the rest of the Greenpeace prisoners rejoined their families. It was, to be sure, a happy ending. Yet it shouldn’t obscure the fact that more than two dozen people had been held hostage by the Russian state after being kidnapped in international waters, that only a lucky confluence of pressure and politics prevented the ordeal from lasting years, and that no such luck is in store for the Arctic itself.

Everything comes together in the Arctic: oil, nostalgia, and the Russian frontier mentality. The flurry of symbolic gestures toward the nation’s frozen north began a decade ago. In 2004, Russia launched the Arctic Clean-Up Project, aimed at reclaiming the far-flung islands that had once been home to military airports and border outposts and now boasted only debris, abandoned airplanes, and thousands of empty fuel barrels, many of which were leaking toxic substances onto the ice. In 2007, Artur Chilingarov, a member of parliament and the country’s most celebrated explorer, descended in a three-man submersible to the bottom of the Arctic Ocean and planted a titanium flag directly beneath the North Pole. (It was a territory-marking gesture worthy of Cortés, and Chilingarov stated its goal without mincing words: “We must prove that the North Pole is an extension of the Russian landmass.”) In 2009, Putin himself became chairman of the board of the Russian Geographical Society, a 169-year-old organization resurrected and lavishly funded for the purpose of reclaiming what it calls the “Russian Arctic.”

On a barely more pragmatic note, Russia also has its eye on the region’s petroleum. In December, Gazprom Neft Shelf, a subsidiary of the state natural-gas monopoly, began drilling on an industrial scale. This gesture, too, is largely symbolic. Even if production reaches its projected capacity of 48 million barrels a year, it will represent a small fraction of all Russian oil — and a wildly overpriced one, since the estimated cost of extracting a barrel from the Arctic fields is as much as $700, or about seven times what that same barrel will currently fetch on the open market.

Preparing for this highly theoretical windfall, Gazprom towed a drilling platform off the coast of Murmansk in 2011 and anchored it in the Pechora Sea. En route, the Prirazlomnaya platform was technically classified as a ship. Once it arrived, however, it became an “ice-resistant stationary platform” — a distinction that would eventually have great legal significance — anchored in international waters. It was also in what is called the “exclusive economic zone” of the Russian Federation, meaning that anyone can sail in these waters but only Russia can engage in economic activity. This detail would also prove to be important, especially once Greenpeace showed up in the summer of 2012 to protest the planned drilling.

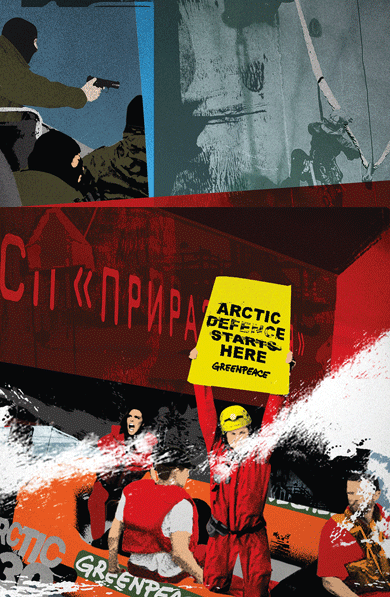

The activists’ first salvo lasted three days and involved scaling the platform to hang banners with slogans like save the arctic and generally making life difficult for the oil company. At one point Greenpeace chained its motorized inflatable dinghy to the anchor of a ship called, lyrically and oddly, the Anna Akhmatova. It was the maritime equivalent of a sit-in, since the ship couldn’t raise anchor without injuring the activists.

The Greenpeace message is simple. Of all the varieties of drilling, the offshore kind is most likely to cause accidents. Of all the countries that engage in offshore drilling, Russia is the most careless in its practices: Greenpeace estimates that about 30 million barrels of oil are spilled or dumped annually in Russia — seven times the amount leaked by BP’s Deepwater Horizon rig into the Gulf of Mexico in 2010. And of all the places to have an oil spill, the Arctic Ocean is among the worst, given the difficulty of cleanup and the detrimental consequences for the global environment.

Although eight of the people on board the Greenpeace vessel that summer spoke Russian, they made a point of communicating in English. “We are a peaceful organization,” the voice over the radio kept insisting. That voice belonged to Litvinov, who speaks American English with a perceptible Swedish accent, which colors his Russian as well: it’s as if all his words are passed through a consonant-softening filter. The activists had the distinct impression that their interlocutors did not understand much English. The Gazprom employees threw scrap metal at the activists climbing the platform, aimed water cannons at their boats, and finally called for the Border Guard. By then, however, Greenpeace was done with its first offensive and departed.

The activists, of course, had their own comprehension difficulties. They failed to grasp the nature of the oil workers’ dismay, and the fact that in 2012 Russian society was undergoing a profound transformation. It was the year the prodemocracy movement peaked and collapsed following Putin’s election to a third term as president. On the eve of Election Day that March, three members of the activist group Pussy Riot had been arrested in Moscow for performing what they called a “punk prayer” inside the city’s largest cathedral. While Greenpeace was carrying out its initial protest in the Arctic, the Pussy Riot performers were on trial in Moscow for “felony hooliganism,” and two dozen other Russians had been locked up on criminal charges stemming from peaceful protest. So aside from their puzzlement over Greenpeace’s English-language communiqués, the Gazprom workers were presumably stunned by their very presence. How could a bunch of punks possibly be staging an elaborate mockery of the Arctic oil effort, which was no less important to the Russian national idea than the Orthodox Church?

By the time the Dutch-registered Arctic Sunrise approached the Prirazlomnaya platform on September 18, 2013, Russia had passed a series of restrictive laws aimed at quashing protest of any kind. Greenpeace would now receive an even chillier welcome than they had back in 2012. A Russian Border Guard ship made radio contact when Litvinov and his companions were still about fifty miles away. “We are here for peaceful protest,” he replied.

The Border Guard warned Greenpeace away from the platform, which had a “safety zone” of three nautical miles and an “exclusion zone” of 500 meters. Greenpeace heeded this standard warning: the organization’s big ships always stop at the edge of the exclusion zone and send protesters in inflatable dinghies. Entering the exclusion zone in these small boats is punishable by a modest fine, which Greenpeace promptly pays.

“As soon as our boats came down, their boats came down,” Litvinov told me, two and a half months after the fact. “Guns come out. Masked men. Shots are fired into the water. Shots are fired into the air.”

What sounded like it took a few minutes must in fact have taken a fair amount longer, because by this time two activists — Marco Weber, from Switzerland, and Sini Saarela, from Finland — were scaling the drilling platform. A third, an Argentine woman named Camila Speziale, was in a dinghy, preparing to begin her ascent. The Russians rammed into Speziale’s inflatable while platform workers aimed water cannons at the two climbers. The Border Guard then grabbed their lines and forced them to descend into the Russian vessels.

Now the Russians, holding two activists on their ship, demanded to be allowed aboard the Arctic Sunrise for an inspection — an unconventional request to make in international waters. Litvinov said no. The Russians threatened to open fire on the ship. “Officer, do you realize what you have just said?” Litvinov responded. “You have just threatened live fire against a Dutch ship in international waters. This is equivalent to a declaration of war.”

The Russian negotiator kept up his demands. Litvinov tried a more lighthearted approach: “You could be in a lot of trouble. This is the official year of Dutch-Russian friendship.” The tone on the other side never changed. For a few hours, both ships were stationary and silent. Then the remaining Greenpeace activists decided to turn around and head back toward the platform.

“What are you doing?” the Russians radioed nervously.

“We are here to do a job, to protest against oil drilling in the Arctic, to bear witness to it.”

The Russians followed. And then the helicopter came. In a video shot on the ship, you can see, against the backdrop of a spectacular Arctic dawn, Greenpeace activists pouring out onto their ship’s helipad and throwing their arms up — not in a sign of surrender, but in an effort to prevent the helicopter from landing. It looks like a ritualistic dance, and it might as well have been, because heavily armed men in olive uniforms, most of them wearing masks, were already rappelling down. You can see them pointing their guns, climbing the stairs to get to the bridge, pushing activists out of the way. Then the video ends.

“The big thing I remember is the size of the guns,” Litvinov told me. “Really huge.” The activists had little sense of how many people had boarded their ship, or who these people were: their clothing and black headgear bore no identifying insignia.

That day and that night the anonymous Russians and some Border Guard officers in uniform looted the ship, ripping out communications equipment and seizing computers and cameras (including those belonging to two freelance journalists). They confiscated the alcohol, much of which they consumed on the spot. They eventually herded the activists and crew into the lounge, where each person was searched and deprived of most personal belongings. The lone exception was Willcox, who was kept on the bridge under guard. He was brought down a few times to get food from the galley: the others saw him, but they were not allowed to talk.

More than two days after the battle of the inflatables began, the Border Guard ship began towing the Arctic Sunrise to Murmansk. The journey took almost four days. During this time, all the detainees aside from the captain were allowed to move around some sections of the ship, and things stabilized, as they have a way of doing. It seemed fair to assume that the trouble would end once the ship got to port — just as it had a quarter century earlier, when Litvinov was first detained in the same area. But the activists, who knew so much about offshore drilling and the fine points of maritime law, still had little idea of what they had gone up against: Russian national ambition itself.

Once the ship docked, the activists were taken off and booked. One of the more curious documents in the Arctic 30 legal files is the protocol of detention. All the detainees were processed at the local investigative office in Murmansk. Four were Russian citizens: two Greenpeace staffers, one doctor, one photojournalist. But nowhere is it explained how the others — twenty-six people from seventeen countries — ended up at 48 Karla Liebknecht Street without entry visas.

After booking, they were taken to a short-term detention facility. “Slam, slam, slam, crank, crank, crank,” was how Willcox recalled the sound of the door closing and locking behind him. He and Litvinov were placed together in a cell along with one non-Greenpeace Russian prisoner. “I’m a little bit claustrophobic, and I just lay there all night listening to my heart. Then Dima and this Russian guy, who is a smoker, started snoring together, and I thought, ‘This is going to be all right.’ ”

Litvinov wasn’t so sure, especially once the lawyer retained by Greenpeace showed up. Larisa Vasilyeva is a joy to watch at work: passionate, intense, and articulate in a plainspoken way — rare qualities all in a Russian courtroom, which tends to be the province of hopelessness and monotony. Her analysis of the situation: “This is serious. They are going to put you away for two months, and during that time they are going to try to prove you are pirates.” The piracy charge, she informed her clients, carried a sentence of ten to fifteen years. “That’s funny,” Litvinov replied. “Ten to fifteen years for waving a banner?”

It was especially funny considering that piracy is defined under Russian law as “an attack on a sea or river ship with the purpose of seizing other persons’ possessions involving the use of violence or the threat of violence.” The violence and threats had come from one source only: the men in olive uniforms. What’s more, there were no ships in the vicinity aside from the Arctic Sunrise and the Border Guard vessel. The drilling platform had legally ceased to be a ship the moment it anchored itself to the bottom of the Pechora Sea.

The Arctic Sunrise, like most modern ships, is equipped with a special alarm button. These have been installed in the past decade or so, as piracy in the southern seas has soared. “I didn’t know where it was,” confessed Willcox. But as soon as the Russians boarded the ship, he rushed over to the second mate and said, “We’ve got a piracy button, right? Push it now.”

Several weeks after the capture of Willcox’s vessel, Captain Phillips was released all over the world. In the movie, Tom Hanks, who plays the titular captain, pushes the button — and immediately sets in motion a robust response from the international antipiracy establishment and the U.S. Navy, which requires only that Hanks and his crew stay alive until the battleships and negotiators and SEALs arrive to rescue them. That’s what happens when a ship piloted by an American captain is boarded in international waters by a bunch of skinny black guys in motorboats. The Arctic Sunrise, on the other hand, was boarded in international waters by a bunch of stocky white guys in helicopters, who had the backing of a major world power, and the response was much less decisive. Even Greenpeace preferred to avoid a militant (much less military) approach. Early on, the organization made a defensible but ultimately unrealistic policy decision: work the diplomatic channels and try to give Putin a way out by blaming the apparent kidnapping on Gazprom rather than on the Russian government.

There were many problems with this position. For one thing, the Russian Border Guard and police and prosecutor’s offices all answer to the Russian president, not to Gazprom. For another, Russian authorities were making clear that they viewed the activists as enemies of the state. On September 24, before most of the Arctic 30 had even been booked, Vladimir Markin, spokesman for the Investigative Committee of Russia, a federal law-enforcement agency, issued a statement that read, in part:

[I]t is difficult to believe that these so-called activists did not know that the drilling tower is a dangerous object and that any unsanctioned actions on it can lead to an accident that would, incidentally, have endangered the lives not only of the people on the platform but also the environment that they are so zealously defending. Whatever the case, in point of fact these actions not only constitute an attack on state sovereignty but also endanger the environmental security of the entire region.

In a series of hearings over five days, the Murmansk courts ordered all of the Arctic 30 to be held for two months on suspicion of piracy. The newly minted inmates were taken to several pretrial detention centers in and around the city. “Welcome to your new home,” a man in sky-blue camouflage told Litvinov. “You’ll be here for a while.” After this greeting, Litvinov and his companions were marched through the prison yard to a series of small concrete boxes covered with grates, differing from conventional cells only in that a small amount of light came through the ceiling.

Having heard about such accommodations his entire life, Litvinov was filled with a sort of exhilaration: “Wow, I know this!” He swiftly identified the kormushka (the small window in the door through which food and other items are passed) and the glazok (the peephole guards use to monitor inmates). “I recognized the clanging of the keys from a story by Varlam Shalamov,” he added, citing a writer who spent nearly twenty years in the gulag. There were four bunks in his cell and only three inmates — something of a luxury. Even more luxuriously, there was a plywood partition separating the living space from the toilet, which Litvinov described as “pretty awesome.”

Russia’s detention centers, jails, prisons, and penal colonies fall into two categories: red and black. In a red zone, the prison administration imposes the rules, which can be more or less inhumane, depending largely on the personality of the warden. A black zone is governed by the inmates themselves, who follow a strict set of rules and rituals passed down since the middle of the twentieth century. In such zones, the administration leaves it up to the inmates to maintain order and punish infractions. In exchange, the inmates are granted a measure of freedom, which often extends to having alcohol and mobile phones. A black zone — which awakens at night, when the systems of intercell communication and trade come deafeningly alive — is one of the most bizarre places in the world. The Murmansk Detention Center No. 1, where all of the Arctic 30 were eventually assembled, is a black zone.

The lifeline of a black zone is the doroga (literally, “road”), an elaborate system of ropes that allows inmates to exchange notes (as well as books, packages, and cigarettes) by placing them inside socks, which then travel from floor to floor and cell to cell until they reach the addressee. Each cell has an inmate, usually someone junior, who stays up all night manning the apparatus, pulling, hanging, pushing, and screaming to other inmates when they need to do their part. Thanks to the doroga — and to shouting out to one another during their so-called walks in the so-called yard — the men of the Arctic 30 were able to stay in touch. The women weren’t so lucky: held in a different section of the detention center, they were seldom able to communicate.

The four Russian inmates shared little of Litvinov’s deep immersion in gulag lore, yet they found life in the black zone fascinating and at least vaguely romantic. Even some of the foreigners got on board, picking up prison slang that later made their Russian friends cringe. Others, like Willcox, found the experience unremittingly awful and unpleasantly mystifying. “The first night I walked into jail,” he recalled, “it was ten o’clock at night and I saw all this string and all these people screaming at each other through the bars, and I thought, ‘Oh my God, it’s the zoo!’ ” It was virtually impossible for a newcomer to avoid violating one arcane rule or another: “I threw out a piece of moldy bread and all of a sudden I had the head of the prison in my face, spit flying.” A representative of a prison-oversight NGO finally had to intervene and broker a resolution, which involved Willcox writing a statement in which he apologized for breaking the taboo on bread disposal and promised never to do it again. “I lost ten kilos in three weeks,” the captain told me. “It wasn’t the food — it was being shit-scared.”

Food, along with warm clothes and other necessities, arrived courtesy of the humanitarian operation Greenpeace had begun setting up in Murmansk within hours of learning of the arrests. When I visited the office, it was in its fourth week of existence, operating around the clock, staffed by activists from all over the world. At that point, in late October, the place was run by Tobias Muenchmeyer, a Greenpeace campaigner from Germany and an old friend of mine. I had seen him in Berlin just two weeks earlier, and he looked like he had aged twenty years since then. “Our main job here is duty of care,” he explained. “To hand over goody bags once a week to each person in the detention centers.”

This was more difficult than it sounded. There were communication problems, and almost all requests went through both a translator and a lawyer. Also, the detention center accepted the copious paperwork for inmate packages only between the hours of nine a.m. and one p.m., and they put similar limits on when the packages themselves could be delivered — at which point a prison staffer cut every single sausage or piece of candy in half to check for contraband. To get a decent spot in the package line, a Greenpeace activist had to get there by four a.m., and with any luck the process would be over eleven hours later.

But there was good news, too. The evening before my arrival, Muenchmeyer told me, the Dutch government had filed a claim in the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS) demanding the immediate release of the Arctic Sunrise and its complement of crew and activists. Getting the Netherlands to tangle with Russia had required a significant lobbying effort. The Dutch argument was simple: the ship had been seized in international waters, the drilling platform was not a ship and therefore could not have been the object of piracy, and in any case there had been no violence on the part of Greenpeace. “Russia actually has a very good track record of obeying international-court rulings,” Muenchmeyer said hopefully, repeating a common misconception. Russia observes many of the rulings made by the European Court of Human Rights because Europe tightly controls the compensation mechanism. But if the court directs Russia to do something that contradicts its national policies or, worse, infringes on its cultural values, the effect is reversed. When the ECHR ruled in 2010 that Moscow had no right to ban a gay-pride parade, Moscow responded by banning such gatherings for the next hundred years.

But there was good news, too. The evening before my arrival, Muenchmeyer told me, the Dutch government had filed a claim in the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS) demanding the immediate release of the Arctic Sunrise and its complement of crew and activists. Getting the Netherlands to tangle with Russia had required a significant lobbying effort. The Dutch argument was simple: the ship had been seized in international waters, the drilling platform was not a ship and therefore could not have been the object of piracy, and in any case there had been no violence on the part of Greenpeace. “Russia actually has a very good track record of obeying international-court rulings,” Muenchmeyer said hopefully, repeating a common misconception. Russia observes many of the rulings made by the European Court of Human Rights because Europe tightly controls the compensation mechanism. But if the court directs Russia to do something that contradicts its national policies or, worse, infringes on its cultural values, the effect is reversed. When the ECHR ruled in 2010 that Moscow had no right to ban a gay-pride parade, Moscow responded by banning such gatherings for the next hundred years.

Defense lawyers hired by Greenpeace appealed the thirty arrest decisions in Murmansk Regional Court. They believed themselves to have a solid case: they’d recorded a slew of procedural violations, and the piracy charge was on its face absurd. But a solid case means nothing in a Russian court that is carrying out orders from on high. And this was clearly going on in Murmansk. At one of the hearings I attended, the judge walked into the courtroom with a printout of his decision before the proceedings even began.

That hearing, on October 22, was for Iain Rogers, the ship’s thirty-seven-year-old British engineer, who was also represented by Vasilyeva. But it was the coordinator of the Greenpeace legal team, a St. Petersburg–based lawyer named Sergei Golubok, who made the most stirring speech of the afternoon — indeed, the most stirring speech I have ever heard in a Russian courtroom. At one point, he shared his suspicions that the prosecutor did “not understand that the Prirazlomnaya platform does not belong to the Russian Federation. It belongs to Gazprom Shelf Neft, a corporation. It is not the territory of the Russian Federation, it is not the property of the Russian Federation — it is private property. No one is allowed to violate human rights in order to protect the interests of Gazprom.” The prosecutor, a woman in her fifties, looked confused: it seemed she really had assumed that the drilling platform was state property.

Golubok then turned to the judge, who looked bored. “I ask the court not to fall into Gazprom’s embrace,” he pleaded, “or into the arms of secret services that do Gazprom’s bidding.”

When the judge left to deliberate, Golubok approached me. “I’m glad you came,” he said. “You can write about our legal arguments, because no one writes about those.” I realized his impassioned speech had been intended for a specific audience: me. Speaking to the court, after all, is useless, and none of the half dozen Greenpeace activists in the room understood Russian. Golubok left without waiting for the decision, which, he said, was preordained. I had never seen a Russian lawyer do that. All of them know, or say they know, that decisions against their defendants are foregone conclusions. Yet they always linger anxiously, hoping for the one-in-a-million chance that their arguments will have swayed a judge.

Half an hour later, Golubok texted me asking what the decision was: he still hoped for a miracle, which did not materialize.

That night at the Park Inn hotel in Murmansk, where the entire Greenpeace team was staying and where a block of rooms was on perpetual reserve in hopes that the Arctic 30 would be released on bail, Golubok staked his hopes on yet another miracle. He was certain that ITLOS would order the Russians to free both the prisoners and the ship. What if Russia refused to comply? He said this was impossible. And what if Russia simply declined to participate in the hearing? He said this was impossible, too.

The same night at the same hotel, Alina Zhiganova told me that nothing was impossible. An event organizer from Moscow, she had flown in to see her husband, Denis Sinyakov, a freelance photographer who had been shooting the Arctic for a couple of years, employed first by Gazprom and now by Greenpeace. His arrest had shocked the Moscow media community. Journalists had been roughed up at protests, dragged into prisoner transports and police precincts — but they had not, as a rule, been booked and imprisoned. Now this, too, was possible.

“I haven’t stopped believing that this is all a silly misunderstanding,” she told me. “But I am a grown-up, and when I make plans for the future, I assume he will not be joining me.”

There was an odd sort of resolve in Zhiganova’s words, but there was no despair. I glimpsed despair three weeks later in Stockholm, where Litvinov and his wife, Anitta, have lived since 1994. Anitta had just been picketing the Russian Embassy, as she had done nearly every afternoon for the previous month — conveniently enough, it was located around the corner from the government building where she worked. We talked for a couple of hours, and she told me that all three of her children, including the two grown ones, thought their dad was Indiana Jones and could easily survive a Russian jail. Then she got up to leave, since fourteen-year-old Luke would be waiting for her at home. She asked if she should take him to see Captain Phillips. I urged caution, saying that the film included a graphic scene in which the captain is nearly killed by his captors.

“Maybe we better see it when Dima comes back,” she said. “If he comes back.” It had been fifty-nine days since the men in olive uniforms descended on the Arctic Sunrise, and the Russian investigators had just filed motions to extend the term of arrest for all thirty prisoners.

Back in Murmansk, the day after Golubok assured me that ITLOS would soon set things right, news came that Russia was refusing to recognize the court’s authority and would not be sending a representative to the hearing on November 6. “Everyone is in shock,” Golubok said, when we met at the Park Inn bar again. Still, he thought the Russians would ultimately cave and attend the hearing: “This kind of behavior is just too blatant. It’s impossible.” He thought for a while and even came up with a face-saving solution for Russia: “I think they’ll just release the people so that there will be no need to attend the tribunal.”

As I boarded a plane out of Murmansk late that night, I got a one-line email from Muenchmeyer: “Russia drops piracy charge!!!” The news, however, was not as good as that line suggested. Russia had indeed found a way to avoid dealing with ITLOS, but it was not the graceful solution envisioned by Golubok. Instead, the Investigative Committee decided to charge the Arctic 30 with felony hooliganism instead of piracy.

The crime is defined as a “gross disruption of the social order that shows a clear disrespect for society and is committed (a) with the use of arms or objects used as arms; (b) on the basis of political, ideological, racial, ethnic, or religious hatred or enmity or on the basis of hatred or enmity for a particular social group.” Precisely which social order the Arctic 30 could have disrupted in the international waters of the Arctic remained unclear. But this was the whole point: hooliganism is the catchall political charge of Putin’s Russia. The members of Pussy Riot were also convicted of felony hooliganism — committed, the court ruled, on the basis of hatred and enmity for the Russian Orthodox Church and not, as one might have thought, on the basis of the group’s opposition to Vladimir Putin. The performance artist Petr Pavlensky, who nailed his scrotum to the cobblestone pavement of Red Square in November 2013 to protest the immobilized state of the Russian public, has been slapped with the same charge.

The only positive development for the Arctic 30 was that the maximum sentence for felony hooliganism is seven years, as opposed to fifteen for piracy. Meanwhile, ITLOS went ahead and heard the case in the absence of the Russians, and soon issued its decision: The ship and the prisoners should be released immediately, but Russia was entitled to set bail while the case was reviewed. Russia said nothing.

On November 11, something finally changed. The Arctic 30 were moved to St. Petersburg, where they were placed in Kresty, an infamous jail that has housed political prisoners for much of its nearly 125-year history. Anna Akhmatova, whose husband and son were held in the prison, once wrote that a monument might well be erected to her on the premises, “where I stood for three hundred hours / And no one slid open the bolt.” A small monument to Akhmatova was indeed placed near the jail in 2006, just as a new age of political trials and political prisoners was beginning in Russia.

For the Arctic 30, the most salient feature of Kresty was that it was a red zone. Willcox’s new cell mate laughed when the captain hesitated to throw out a piece of moldy bread: the superstitions and rituals of the prisoner-run world did not apply here. Meanwhile, the judiciary continued to send mixed signals about the whole matter. First, on November 18, two St. Petersburg courts began reviewing the Investigative Committee’s requests to extend the term of arrest for each of the prisoners. Colin Russell, the ship’s Australian radio operator, went up first. The court extended his pretrial-detention term until February 24 — a longer extension than usual, but presumably timed to avoid another round of embarrassing hearings right before the Olympic Games in Sochi.

That same evening, a group of Moscow photographers held an auction to benefit Denis Sinyakov (the specific goal was to publish a book of his photojournalism). Just before the auction began, in a swank space off Red Square, news came that Ekaterina Zaspa, the Arctic Sunrise’s Russian doctor, had been released on 2 million rubles’ bail (approximately $60,000). Quick discussions among Russian opposition types yielded a couple of interpretations: the courts were releasing only the women, as they have sometimes done in large political prosecutions; or they were releasing only the Russian citizens, whose passports could be confiscated to prevent their leaving the country before trial. Since Russell had not been released, nobody thought the entire group would be getting out on bail.

“It’s ridiculous that people have to pay to be released from jail,” said a younger photographer.

“First of all, they’ll get the money back,” said an older colleague. “Second, if Stalin were alive today, they would all have been executed by now.”

I spoke to Golubok at 8:30, and he had some more news. Just before the court broke for the evening, the prosecutor in Ana Paula Alminhana Maciel’s case had changed his position and asked that she, too, be released on bail.

“Wow,” I said.

“Wow is right,” said Golubok.

“Is this it?” I asked. “Is this the moment when you actually got through to one of them?”

“Yes, it is,” said the lawyer.

It was not. The following day, the St. Petersburg courts began rubber-stamping 2-million-ruble bail verdicts, just as they had rubber-stamped arrests before. It seemed that Russell had simply been unlucky: the order from on high had not yet come in when his hearing began (he was released on bail the following week). Golubok’s eloquence, then, had had nothing to do with the prosecutor’s change of heart: like so many matters in a modern police state, it had been decided by a phone call.

Now Greenpeace quietly replaced Golubok as the coordinator of its legal team. The new coordinator was a former prosecutor who knew the ins and outs of the St. Petersburg penitentiary system — and his skill at whipping paperwork through the right channels ensured that even Litvinov, whose hearing was that Friday afternoon, spent the weekend in a hotel instead of a cell.

We met a few days later, in a hotel room Greenpeace was using for meetings with the media. The room was on the top floor and had a low ceiling that forced Litvinov to duck at one point. “Reminds me of Kresty,” he said. As we talked about all the events since September 18, Anitta, who had flown in a day earlier, sat quietly in an armchair in the corner, occasionally pecking at her tablet. It turned out to be a long conversation, and at some point we went downstairs to the hotel restaurant to join Willcox for dinner.

A few days earlier, the captain had told a Guardian correspondent that the experience had made him re-evaluate his protest methods. Now he told me that he had changed his mind again. “I remember being scared,” he said, “but I no longer remember the feeling. Two months is not a big deal to save the planet. Five, ten, fifteen years — that would be too much.”

Sinyakov joined us. He had already visited his family in Moscow and thrown a party to thank all of his supporters at a club, where they served marine-themed refreshments and he handed out long-stemmed white roses to many members of the media community. Now a summons from the Investigative Committee had brought him back to St. Petersburg. On the advice of their lawyers, most of the Arctic 30 were refusing to testify, but they were still obliged to show up when summoned as a condition of their bail.

Sinyakov brought up the rumor that the Arctic 30 would be included in an impending amnesty bill — which is exactly what happened on December 18, when the Duma approved Putin’s P.R.-driven display of magnanimity, supposedly designed to mark the twentieth anniversary of the current Russian constitution. “I’m going to refuse their amnesty,” he said.

“Why would you do that?” asked Litvinov.

“Because I’m innocent. I’m going to go to trial to protect the lives of journalists.”

Golubok had joined us now, and Sinyakov asked him about the ITLOS decision: “Why is Russia spitting on it?”

“It’s not spitting on it.” Golubok smiled a tired smile. “It’s carrying it out partially,” he said, noting that Sinyakov was here in the hotel dining room and not in Kresty. The ship, of course, had not been released — perhaps because, according to Willcox, it had been so thoroughly stripped of equipment that showing it to the world was no longer an option.

The former inmates (who might well have been future inmates too) kept slipping into reminiscences, comparing notes on the two months they had spent in close quarters but mostly in isolation from one another. Litvinov, the only one to have been punished with placement in a special isolation cell, said, “I was in it for twenty-nine hours. I was counting the minutes. You count to three hundred: that’s five minutes. You do that twelve times: that’s an hour.” Everyone at the table cringed.

“I never expected the Spanish Inquisition!” Litvinov said, lightening the mood with an old Monty Python riff.

“Nobody expects the Spanish Inquisition!” Anitta said, playing along.

The group asked Golubok what would happen to them. It was still hard to understand the particulars of their legal limbo. The foreigners had been released from jail with papers indicating that they were on Russian territory legally, but they had no visas to mark their entry, which meant they could not exit the country. Within two weeks, the euphoria of their release would fade, and they would face the prospect of spending Christmas in a St. Petersburg hotel — and the scarier prospect of being trapped there through January and February, after which the Olympic Games would end and Russia would no longer worry about how it was seen by the rest of the world, to the extent it even worried about it now.

Golubok, ever the optimist, suggested that if someone managed to get a Russian official to issue an order allowing the foreigners to leave, the Investigative Committee would seize the opportunity to drop the case. After all, the suspects would then be out of reach.

“They are in for some trouble,” said Litvinov. “The Europeans will come back for hearings. The Australians and the New Zealanders will just not bother going home.” He, for one, was intent on facing a Russian court and using that opportunity to speak his mind. Of course he was: he was born for this.

But sometimes fulfilling your destiny — doing something that comes as naturally to you as breathing — becomes difficult or even impossible. After the parliament passed Putin’s amnesty bill, law-enforcement authorities were apparently directed to wrap up the Arctic 30 case at top speed. It was imperative that they get the activists out of the judiciary’s hair. The former inmates were summoned to the Investigative Committee offices in St. Petersburg to sign their amnesty papers. Those who refused, insisting on the public hearing guaranteed to them by Russian law, were browbeaten. They were told that the amnesty was an all-or-nothing arrangement, applicable only to the group as whole. They were told that personal belongings taken into evidence could not be released if there was going to be a court hearing. They were told whatever would persuade them to sign the papers — and ultimately, all thirty signed. “Please don’t congratulate me,” said Sinyakov when I saw him the next day. “I have been disgraced.”

Two months later, he was still waiting for most of his photographic equipment to be returned. The Dutch king and prime minister fêted Putin in Sochi, and on March 17, Greenpeace filed a lawsuit before the European Court of Human Rights. The group demanded compensation from the Russian government, as well as a public admission that their detention had been illegal from the start. It would, alas, take a year or more before the court heard the case. And what of the Arctic Sunrise? The ship was still docked in Murmansk.