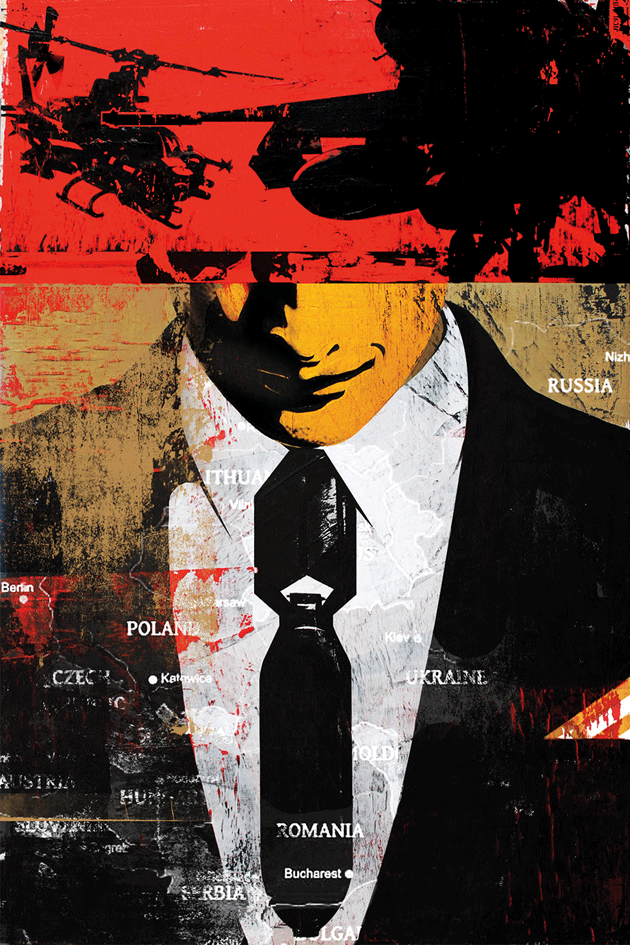

On February 28, 2014, Russian troops effortlessly seized control of Crimea. Two days later, Congressman Mike Rogers, Republican of Michigan and chairman of the House Intelligence Committee, denounced the Obama Administration’s weak response to the crisis. “Putin is playing chess and I think we are playing marbles, and I don’t think it’s even close,” Rogers said on Fox News Sunday. Not long afterward, as the crisis escalated, Rogers hosted a breakfast fund-raiser in downtown Washington.

As befitted an overseer of the nation’s almost $70 billion intelligence budget, Rogers attracted a healthy crowd, largely composed of lobbyists for defense contractors. Curious as to how the military-industrial complex was reacting to events abroad, I asked a lobbyist friend who had attended (but was loath to reveal his identity and thus his communication with a liberal magazine) about the mood at the meeting. “I’d call it borderline euphoric,” he said.

Just a few months earlier, the outlook for the defense complex had looked dark indeed. The war in Afghanistan was winding down. American voters were regularly informing pollsters that they wanted the United States to “mind its own business internationally.” The dreaded “sequester” of 2013, which threatened to cut half a trillion dollars from the long-term defense budget, had been temporarily deflected by artful negotiation, but without further negotiations the defense cuts were likely to resume with savage force in fiscal 2016. There was ugly talk of mothballing one of the Navy’s nuclear-powered carriers, slashing the Army to a mere 420,000 troops, retiring drone programs, cutting headquarters staffs, and more.

Times had been dark before, sometimes rendered darker in the retelling. Although defense budgets had actually increased in the post-Vietnam 1970s, for example, veterans of the era still shared horror stories about the “hollow” military in the years following the final withdrawal from Saigon. That cloud had lifted soon enough, thanks to sustained efforts — via the medium of suitably adjusted intelligence assessments — to portray the Soviet Union as the Red Menace, armed and ready to conquer the Free World.

On the other hand, the end of the Cold War and the collapse of the Soviet Union had posed a truly existential threat. The gift that had kept on giving, reliably generating bomber gaps, missile gaps, civil-defense gaps, and whatever else was needed at the mere threat of a budget cut, disappeared almost overnight. The Warsaw Pact, the U.S.S.R.’s answer to NATO, vanished into the ash can of history. Thoughtful commentators ruminated about a post–Cold War partnership between Russia and the United States. American bases in Germany emptied out as Army divisions and Air Force squadrons came home and were disbanded. In a 1990 speech, Senator Sam Nunn of Georgia, revered in those days as a cerebral disperser of military largesse, raised the specter of further cuts, warning that there was a “threat blank” in the defense budget and that the Pentagon’s strategic assessments were “rooted in the past.” An enemy had to be found.

For the defense industry, this was a matter of urgency. By the early 1990s, research and procurement contracts had fallen to about half what they’d been in the previous decade. Part of the industry’s response was to circle the wagons, reorganize, and prepare for better days. In 1993, William Perry, installed as deputy defense secretary in the Clinton Administration, summoned a group of industry titans to an event that came to be known as the Last Supper. At this meeting he informed them that ongoing budget cuts mandated drastic consolidation and that some of them would shortly be out of business.

Perry’s warning sparked a feeding frenzy of mergers and takeovers, lubricated by generous subsidies at taxpayer expense in the form of Pentagon reimbursements for “restructuring costs.” Thus Northrop bought Grumman, Raytheon bought E-Systems, Boeing bought Rockwell’s defense division, and the Lockheed Corporation bought the jet-fighter division of General Dynamics. In 1995 came the biggest and most consequential deal of all, in which Martin-Marietta merged with Lockheed.

The resultant Lockheed Martin Corporation, the largest arms company on earth, was run by former Martin-Marietta CEO Norman R. Augustine, by far the most cunning and prescient executive in the business. Wired deeply into Washington, Augustine had helped Perry craft the restructuring subsidies for companies like his own — essentially, a multibillion-dollar tranche of corporate welfare. In a 1994 interview, he shrewdly predicted that U.S. defense spending would recover in 1997 (he was off by only a year). In the meantime, he would scour the world for new markets.

In this task, Augustine could be assured of his government’s support, since he was a member of the little-known Defense Policy Advisory Committee on Trade, chartered to provide guidance to the secretary of defense on arms-export policies. One especially promising market was among the former members of the defunct Warsaw Pact. Were they to join NATO, they would be natural customers for products such as the F-16 fighter that Lockheed had inherited from General Dynamics.

There was one minor impediment: the Bush Administration had already promised Moscow that NATO would not move east, a pledge that was part of the settlement ending the Cold War. Between 1989 and 1991, the United States and the Soviet Union had amicably agreed to cut strategic nuclear forces by roughly a third and to withdraw almost all tactical nuclear weapons from Europe. Meanwhile, the Soviets had good reason to believe that if they pulled their forces out of Eastern Europe, NATO would not fill the military vacuum left by the Red Army. Secretary of State James Baker had unequivocally spelled out Washington’s end of that bargain in a private conversation with Mikhail Gorbachev in February 1990, pledging that NATO forces would not move “one inch to the east,” provided the Soviets agreed to NATO membership for a unified Germany.

The Russians certainly thought they had a deal. Sergey Ivanov, later one of Vladimir Putin’s defense ministers, was in 1991 a KGB officer operating in Europe. “We were told . . . that NATO would not expand its military structures in the direction of the Soviet Union,” he later recalled. When things turned out otherwise, Gorbachev remarked angrily that “one cannot depend on American politicians.” Some years later, in 2007, in an angry speech to Western leaders, Putin asked: “What happened to the assurances our Western partners made after the dissolution of the Warsaw Pact? Where are those declarations today? No one even remembers them.”

Even at the beginning, not everyone in the administration was intent on honoring this promise. Robert Gates noted in his memoirs that Dick Cheney, then the defense secretary, took a more opportunistic tack: “When the Soviet Union was collapsing in late 1991, Dick wanted to see the dismantlement not only of the Soviet Union and the Russian empire but of Russia itself, so it could never again be a threat to the rest of the world.” Still, as the red flag over the Kremlin came down for the last time on Christmas Day, President George H. W. Bush spoke graciously of “a victory for democracy and freedom” and commended departing Soviet leader Gorbachev.

But domestic politics inevitably dictate foreign policy, and Bush was soon running for reelection. The collapse of the country’s longtime enemy was therefore recast as a military victory, a vindication of past imperial adventures. “By the grace of God, America won the Cold War,” Bush told a cheering Congress in his 1992 State of the Union address, “and I think of those who won it, in places like Korea and Vietnam. And some of them didn’t come back. Back then they were heroes, but this year they were victors.”

This sort of talk was more to the taste of Cold Warriors who had suddenly found themselves without a cause. The original neocons, though reliably devoted to the cause of Israel, had a related agenda that they pursued with equal diligence. Fervent anti-Communists, they had joined forces with the military-industrial complex in the 1970s under the guidance of Paul Nitze, principal author in 1950 of the Cold War playbook — National Security Council Report 68 — and for decades an ardent proponent of lavish Pentagon budgets. As his former son-in-law and aide, W. Scott Thompson, explained to me, Nitze fostered this potent union of the Israel and defense lobbies through the Committee on the Present Danger, an influential group that in the 1970s crusaded against détente and defense cutbacks, and for unstinting aid to Israel. The initiative was so successful that by 1982 the head of the Anti-Defamation League was equating criticism of defense spending with anti-Semitism.

By the 1990s, the neocon torch had passed to a new generation that thumped the same tub, even though the Red Menace had vanished into history. “Having defeated the evil empire, the United States enjoys strategic and ideological predominance,” wrote William Kristol and Robert Kagan in 1996. “The first objective of U.S. foreign policy should be to preserve and enhance that predominance.” Achieving this happy aim, calculated these two sons of neocon founding fathers, required an extra $60–$80 billion a year for the defense budget, not to mention a missile-defense system, which could be had for upward of $10 billion. Among other priorities, they agreed, it was important that “NATO remains strong, active, cohesive, and under decisive American leadership.”

As it happened, NATO was indeed active, under Bill Clinton’s leadership, and moving decisively to expand eastward, whatever prior Republican understandings there might have been with the Russians. The drive was mounted on several fronts. Already plushly installed in Warsaw and other Eastern European capitals were emissaries of the defense contractors. “Lockheed began looking at Poland right after the Wall came down,” Dick Pawloski, for years a Lockheed salesman active in Eastern Europe, told me. “There were contractors flooding through all those countries.”

Meanwhile, a coterie of foreign-policy intellectuals on the payroll of the RAND Corporation, a think tank historically reliant on military contracts, had begun advancing the artful argument that expanding NATO eastward was actually a way of securing peace in Europe, and was in no way directed against Russia. Chief among these pundits was the late Ron Asmus, who subsequently recalled a RAND workshop held in Warsaw, just months after the Wall fell, at which he and Dan Fried, a foreign-service officer deemed by colleagues to be “hard line” toward the Russians, and Eric Edelman, later a national-security adviser to Vice President Cheney, discussed the possibility of stationing American forces on Polish soil.

Eminent authorities weighed in with the reasonable objection that this would not go down well with the Russians, a view later succinctly summarized by George F. Kennan, the venerated architect of the “containment” strategy:

Expanding NATO would be the most fateful error of American policy in the post cold-war era. Such a decision may be expected to inflame the nationalistic, anti-Western and militaristic tendencies in Russian opinion; to have an adverse effect on the development of Russian democracy; to restore the atmosphere of the cold war to East-West relations, and to impel Russian foreign policy in directions decidedly not to our liking.

In retrospect, Kennan seems as prescient as Norm Augustine, but it didn’t make any difference at the time. When he wrote that warning, in 1997, NATO expansion was already well under way, and with the aid of a powerful supporter in the White House. “This mythology that it was all neocons in the Bush Administration, it’s nonsense,” says a former senior official on both the Clinton and Bush National Security Council staffs who requested anonymity. “It was Clinton, with the help of a lot of Republicans.”

This official credits the persuasive powers of Lech Wa?e sa and Václav Havel at a 1994 summit meeting with Clinton’s conversion to the cause of NATO expansion. Others point to a more urgent motivation. “It was widely understood in the White House that [influential foreign-policy adviser Zbigniew] Brzezinski told Clinton he would lose the Polish vote in the ’96 election if he didn’t let Poland into NATO,” a former Clinton White House official, who requested anonymity, assured me.

To an ear as finely tuned to electoral minutiae as the forty-second president’s, such a warning would have been incentive enough, since Polish Americans constituted a significant voting bloc in the Midwest. It was no coincidence then that Clinton chose Detroit for his announcement, two weeks before the 1996 election, that NATO would admit the first of its new members by 1999 (meaning Poland, the Czech Republic, and Hungary). He also made it clear that NATO would not stop there. “It must reach out to all the new democracies in Central Europe,” he continued, “the Baltics and the new independent states of the former Soviet Union.” None of this, Clinton stressed, should alarm the Russians: “NATO will promote greater stability in Europe, and Russia will be among the beneficiaries.” Not everyone saw things that way; in Moscow there was talk of meeting NATO expansion “with rockets.”

Chas Freeman, the assistant secretary of defense for international security affairs from 1993 to 1994, recalls that the policy was driven by “triumphalist Cold Warriors” whose attitude was, “The Russians are down, let’s give them another kick.” Freeman had floated an alternate approach, Partnership for Peace, that would avoid antagonizing Moscow, but, as he recalls, it “got overrun in ’96 by the overwhelming temptation to enlist the Polish vote in Milwaukee.”

In April 1997, Augustine took a tour of his prospective Polish, Czech, and Hungarian customers, stopping by Romania and Slovenia as well, and affirmed that there was great potential for selling F-16s. Clinton had spoken of NATO being as big a boon for Eastern Europe as the Marshall Plan had been for Western Europe after the Second World War, and many of the impoverished ex-Communist countries, some with small and ramshackle militaries, were eager to get on the bandwagon. “Augustine would look them in the eye,” recalls Pawloski, the former Lockheed salesman, “and say, ‘You may have only a small air force of twenty planes, but these planes will have to play with the first team.’ Meaning that they’d be flying with the U.S. Air Force and they would need F-16s to keep up.” Actually, Augustine had rather more going for him than this simple sales pitch, including a lavish dinner for Hungarian politicians he threw at the Budapest opera house.

Meanwhile, back in Washington, a new and formidable lobbying group had come on the scene: the U.S. Committee to Expand NATO. Its cofounder and president, Bruce P. Jackson, was a former Army intelligence officer and Reagan-era Pentagon official who had dedicated himself to the pursuit of a “Europe whole, free and at peace.” His efforts on the committee were unpaid. Fortunately, he had kept his day job — working for Augustine as vice president for strategy and planning at the Lockheed Martin Corporation.

Jackson’s committee stretched ideologically from Paul Wolfowitz and Richard Perle (known as the neocon “Prince of Darkness”) to Greg Craig, director of Bill Clinton’s impeachment defense and later Barack Obama’s White House counsel. Others on the roster included Ron Asmus, Richard Holbrooke, and Stephen Hadley, who subsequently became George W. Bush’s national-security adviser.

When I reached Jackson recently at his residence in Bordeaux, he reiterated what he had always said at the time: his efforts to expand NATO were undertaken independently of his employer. He suggested that they had even imperiled his job. “I would not say that senior executives supported my specific projects,” Jackson said. “They thought I should be free to do what I wanted politically, provided I did not associate [Lockheed] with my personal causes. In short, they did nothing to stop me, and suggested to other employees to leave me alone so long as I did not drag LMC into politics or foreign policy. I finally left because I enjoyed my nonprofit work more than my day job.”

In this atmosphere of disinterested public service, Jackson and his friends devoted their evenings to cultivating support for congressional approval of Polish, Czech, and Hungarian membership in NATO, followed by further expansion. The setting for these efforts was a large Washington mansion not far from the British Embassy and the vice-presidential residence: the home of Julie Finley, a significant figure in Republican Party politics at that time who had, as she told me, “a deep interest in national security.” A friend of hers, Nina Straight, describes Finley as someone who “knows how to be powerful and knows how to be useful.” As Finley relates, she noted in late 1996 that NATO expansion was facing opposition in Washington. “So I called Bruce Jackson and Stephen Hadley and Greg Craig and said, ‘Holy smokes, we have to get moving!’ ”

“We always met at Julie Finley’s house, which had an endless wine cellar,” Jackson reminisced happily. “Educating the Senate about NATO was our chief mission. We’d have four or five senators over every night, and we’d drink Julie’s wine while people like [Polish dissident] Adam Michnik told stories of their encounters with the secret police.”

Meanwhile, other European countries were experiencing a less congenial form of lobbying. Romania, for example, was among those hoping to join the alliance and enjoy the supposed fruits of this latter-day Marshall Plan. But the country was in ruins, with an economy that had barely recovered from the levels induced by the demented economic policies of Nicolae Ceausescu, the tyrannical ruler who had been overthrown and executed in 1989. A 1997 World Bank report noted that “the majority of the poor live in traditional houses made of mud and straw, do not have access to piped water and have no sewage facilities.” Such dire conditions made little impression on visiting arms salesmen. Representatives of Bell Helicopter Textron, manufacturer of the Cobra attack helicopter, persuaded the Romanian government in 1996 to agree to a $1.4 billion deal for ninety-six Super Cobra helicopters, to be manufactured locally and rechristened the Dracula.

This presented Daniel Daianu, a respected economist appointed Romania’s finance minister in December 1997, with a problem. His country didn’t have the money. “There were huge payments, billions, coming due in ’98 and ’99, in external debt payments,” he told me. “That was why I was so against the deal.” In response, the United States applied leverage. Picking his words carefully, Daianu explained that Americans in Washington and Bucharest “intimated to me with clarity that this was the way to get easier access into NATO” — in the first round, along with Poland and the others.

Daianu was learning some interesting things about the way Washington works. He found himself the object of “gentle pressure” from “American businesspeople and people who were a sort of conduit between the American administration of the time and the companies involved in this deal.” As he stuck to his principles, the pressure from such people “intimated” that “this is the way to take care of your retirement, and your children’s.”

At the same time, there was pressure back in Washington, some of it not so gentle. Romania was heavily dependent on an IMF loan guarantee, which gave the fund considerable leverage over the country’s budget. As it happened, Karin Lissakers, the U.S. executive director on the IMF’s board during the Clinton Administration, knew a lot about the sales practices of arms corporations — she had worked during the 1970s for Senator Frank Church’s Subcommittee on Multinational Corporations. The subcommittee had delved into the unwholesome sales techniques of U.S. arms corporations abroad, uncovering many egregious cases of bribery. So when a Textron representative came calling to demand that the fund remove the block it had effectively imposed on the Romanian deal, she was not impressed.

Her visitor, Richard Burt, had been a New York Times reporter specializing in national-security issues before moving over to the State Department, where he ultimately served as ambassador to West Germany. After leaving government service in 1991, he found steady employment as a high-powered consultant. Among his clients was the Textron Corporation (he sat on the firm’s international advisory council), and he had a separate connection to Bell Helicopter, from which a company he chaired, IEP Advisors, had collected $160,000 between 1998 and 1999 for lobbying. Meanwhile, Burt maintained a useful foothold in the Pentagon, serving on the influential Defense Policy Board.

“Rick Burt came to see me and said the IMF was being completely unreasonable in blocking the helicopter deal,” Lissakers told me. “He wanted me to pressure the IMF country team, pressure them to approve the loan. His tone was bullying — the implication was that I was accountable to Congress and would suffer consequences. This was at a time when hospitals in Bucharest had no running water! I always regret I didn’t throw him straight out of my office.”

“She’s full of shit, and that’s on the record,” responded Burt heatedly when I relayed Lissaker’s comments. “That’s not at all what I was doing. I was not pimping for this at all.” He insisted that he himself always thought the helicopter deal was a bad idea, and was simply sounding out the IMF position. He also insisted that the $160,000 IEP Advisors was paid in 1998–99 was merely for “advice — not lobbying.”

Daianu resigned and the helicopter deal was canceled, but Romania did finally make it into NATO, in 2004, along with six other countries. By that time, Lockheed had scored a major payoff with a $3.5 billion sale of F-16s to Poland, and the newly enlarged NATO had proved its military usefulness in the U.S.-led coalition that bombed Serbia, a Russian ally, for seventy-seven days in 1999 on behalf of Kosovo separatists. “The Russians were humiliated in Kosovo,” Jackson said, “and that was the first time they showed militant opposition to NATO.”

Their protests made little difference. “ ‘Fuck Russia’ is a proud and long tradition in U.S. foreign policy,” Jackson pointed out to me. “It doesn’t go away overnight.” Consequently, no one in Washington appeared to care very much about the Russian reaction when NATO’s eastward flow began spilling into the territory of the former Soviet Union, especially once George W. Bush was in the White House with Dick Cheney by his side.

With the momentum of expansion carrying NATO ever closer to the Soviet heartland, it was no longer realistic to presume Russian indifference. Yet the movement was hard to stop. Even farther to the east, in Georgia, a charismatic young U.S.-trained lawyer, Mikheil Saakashvili, took power in 2003 and straightaway began offering a welcome embrace to Washington and pleading to join the alliance. As I have previously described (in a post on the Harper’s website), to bolster his standing in the American capital, Saakashvili hired Randy Scheunemann, a Republican lobbyist and the executive director of the Committee for the Liberation of Iraq, a neocon group formed in 2002 under the chairmanship of none other than Bruce Jackson.

Privately, Washington players felt a little nervous about their hyperactive protégé, suspecting that he might get everyone into trouble. As one of them told me, Saakashvili “needed a course of Ritalin to shut him up.” But in public, it was easy to get swept away. In 2005, George W. Bush stood in Tbilisi’s Freedom Square and told the crowd they could count on American support:

As you build a free and democratic Georgia, the American people will stand with you. . . . As you build free institutions at home, the ties that bind our nations will grow deeper, as well. . . . We encourage your closer cooperation with NATO.

Saakashvili worked hard at ingratiating himself with the friendly superpower, supplying a Georgian contingent for the U.S.-led coalitions in Iraq and Afghanistan, and offering hospitality to various American intelligence operations in Georgia itself, where NSA interception facilities began appearing on suitably sited hilltops. Although he may have had less appeal among European leaders, in Washington the Georgian president basked in bipartisan favor among influential figures such as Richard Holbrooke, as well as White House aspirant Senator John McCain and his adviser (and Saakashvili lobbyist) Randy Scheunemann.

Unfortunately, the burgeoning relationship promoted a dangerous overconfidence on Saakashvili’s part. By 2008, he was unabashedly provoking Moscow, apparently confident that he could win a war with his immense neighbor. Receiving Bruce Jackson, who by now was heading up yet another entity, the Project on Transitional Democracies, Saakashvili demanded immediate shipment of various weapons systems, including, remembers Jackson, “a thousand Stingers.” Jackson said that would not happen. “Go fuck yourself,” snapped the Georgian leader.

Matters came to a head at a NATO summit in Bucharest in April 2008. Vladimir Putin flew in to say that the alliance’s expansion posed a “direct threat” to Russia. President Bush, accompanied by National Security Adviser Stephen Hadley, took Saakashvili aside and told him not to provoke Russia. Sources privy to the meeting tell me that Bush warned the Georgian leader that if he persisted, the United States would not start World War III on his behalf.

Bush had arrived in Bucharest eager for an agreement on rapid NATO membership for Georgia and Ukraine, but he backed off in the face of protests from European leaders. In an awkward compromise, NATO released a statement forswearing immediate membership, but also stating: “We agreed today that these countries will become members of NATO.” Putin duly took note.

Buoyed by hubris and undeterred by warnings (possibly undermined by back-channel assurances from Dick Cheney that he had U.S. support for a confrontation), Saakashvili pressed on, ultimately assaulting the separatist region of South Ossetia, which was disputed by Russia. Russian forces swiftly counterattacked and were soon deep in Georgian territory, making sure along the way to destroy all those U.S. listening posts.

Despite this debacle, appetite for engagement on the fringes of Russia itself did not go away. Cheney and the rest of the Bush Administration were shortly to make way for the new broom of Obama and his team — or nearly new. As is so often the case in important matters, policy proved to be bipartisan. Thus Dan Fried, a senior foreign-policy official under Clinton and Bush, was still in office to welcome the Obama Administration, and currently supervises the sanctions regime directed at Russia for the State Department. Victoria Nuland, wife of Robert Kagan and chief of staff to Clinton’s deputy secretary of state, Strobe Talbot, served Cheney as deputy national-security adviser, then resurfaced as Hillary Clinton’s spokesperson in the first Obama term before transitioning to assistant secretary of state for Europe in the second.

Reacting to the news that the United States had put $5 billion into democracy-building projects in Ukraine, Putin, whose popularity at home had been sagging, pressured Ukraine’s elected president, Viktor Yanukovych, to forgo a trade agreement with the European Union. In its place he offered $15 billion in economic assistance. The rest, as they say, is history. When street protests in Kiev threatened to overthrow the corrupt Yanukovych, Nuland hurried to the scene, distributed bread to the protesters, and later incautiously discussed her plans for installing a new government on an open phone line (“that would be great, I think, to help glue this thing . . . and, you know, fuck the EU”), remarks that were intercepted and promptly leaked. Even a politician far less paranoid than the Russian leader might have found grounds for suspecting that the Americans were up to something, and Putin promptly responded by seizing control of Crimea. Since that moment, as news anchor Diane Sawyer announced in March, it has been “game on” for the United States and Russia.

For many of its original protagonists, NATO expansion has proved an unblemished success. “I see no empirical evidence that enlargement was threatening to Russia,” Jackson told me firmly. “You can’t prove that.” On the other hand, he is no great enthusiast for the economic warfare against Russia levied by the Obama Administration in support of Ukraine. “The moral defense of international intervention is the improvement of the freedom and prosperity of the people in question,” he wrote me recently. “I suspect sanctions will lead to the impoverishment of all concerned, most particularly the Ukrainians [whom] the sanctions policy purports to defend.”

In any event, the vision of Augustine and his peers that an enlarged NATO could be a fruitful market has become a reality. By 2014, the twelve new members had purchased close to $17 billion worth of American weapons, while this past October Romania celebrated the arrival of Eastern Europe’s first $134 million Lockheed Martin Aegis Ashore missile-defense system.

The ebullience expressed by defense lobbyists at Mike Rogers’s breakfast back in March has been amply justified. “Vladimir Putin has solved the sequestration problem for us because he has proven that ground forces are needed to deter Russian aggression,” declared Congressman Mike Turner, an Ohio Republican and chair of an important defense subcommittee, in October. Meanwhile, the Bipartisan Policy Center, a Washington entity that numbers, inevitably, Norm Augustine among the panjandrums adorning its board of directors, sponsored a panel on “Ensuring a Strong U.S. Defense for the Future.” Michèle Flournoy, defense undersecretary for policy during Obama’s first term, warned the panel, “You can’t expect to defend the nation under sequestration.” Fellow panelist and former Cheney adviser Eric Edelman, who preceded Flournoy in the Pentagon post, echoed her theme. Other speakers demanded that NATO members increase their defense budgets.

At the end of October 2014, as European economies quivered, thanks in part to the sanctions-driven slowdown in trade with Russia, the United States reported a gratifying 3.5 percent jump in gross domestic product for the quarter ending September 3. This spurt was driven, so government economists reported, by a sharp uptick in military spending.