Pro- and anti-Trump demonstrators are facing off noisily outside the convention center in Tampa, Florida. A short woman with frizzy gray hair holds a Bible in one hand and a bullhorn in the other: WE PRAY . . . FATHER GOD . . . THAT YOU . . . WILL MAKE . . . AMERICA . . . GREAT AGAIN. Nose to nose, screaming, are a middle-aged white man with a goatee and a skinny black kid with a backward baseball cap that reads comme des fuckdown. “The Koran teaches: Smite the infidel above the neck,” Goatee yells. WE PRAY . . . WE PRAY LORD JESUS . . . THAT NO ONE . . . COMES INTO THIS NATION . . . THAT YOU!!! . . . DO NOT WANT HERE. Comme des FuckDown bellows back: “I see a cop roll down the street, some racist cop having a bad day, I’m in fear for my life.” WE PRAY . . . FATHER GOD . . . THAT NO WEAPON . . . FORMED AGAINST THIS NATION . . . SHALL PROSPER.

Heads turn as a black stretch limo with trump 2016 in gold letters on the side glides slowly past. It stops down the street, then a mop of blond hair and a dark suit gets out. I had first seen the owner of the limo months earlier in New Hampshire. He was negotiating. “It’s twenty dollars,” he told a woman who wanted a make america great again hat. “They cost me money. I gotta charge.” They haggled; ten dollars. Half price, not the most brilliant business deal, but then this wasn’t the real Donald Trump. He used to be Gary Shipko. He changed his name to “Donald Trump” as an homage. If you don’t believe him, he’ll get out his driver’s license and credit cards, all bearing the famous name. He has been “Trump” for four years. When the real Trump began his run for the presidency, Shipko — Donald Trump Junior, as he sometimes calls himself — decided to help.

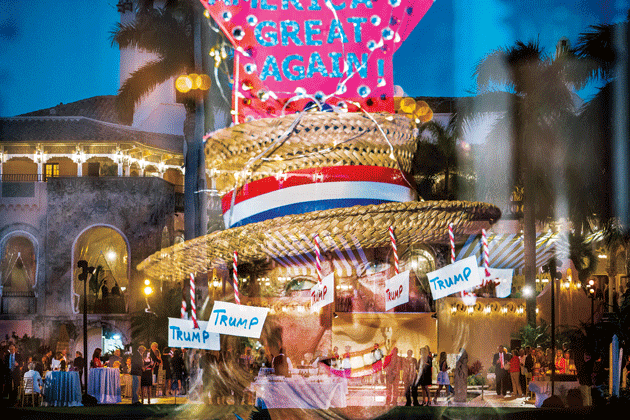

Donald Trump speaking at a press conference in Milford, New Hampshire, before a rally; a fence enclosing a housing community in Homestead, Florida, home to a large number of undocumented immigrants. All multiple-exposure photographs by Mark Abramson for Harper’s Magazine, from his series Two Face

When I first met Trump Junior, in New Hampshire, it seemed to me that going with him to some Trump rallies would be an interesting lens through which to view the presidential race. Back then, he was driving an old police cruiser he had covered in Trump stickers, the passenger seat occupied by a female mannequin in police uniform. “She’s got the gun, the bullets, everything. I put lipstick on her. Everybody says she’s hot looking. Ivanka Trump: that’s her name.”

Donald, formerly Gary, looks the part: the jowls, the glare, the furrowed brow, the dyed blond comb-over. Now sixty, he was by his account a successful businessman once, running a company that made superglue. “Because of that I met a lot of presidents, politicians, superstars. I was worth eight million dollars. I had a mansion. I had a yacht in Florida. I had more money than all my friends. They started calling me Donald Trump Junior because I had the bucks.” Then his marriage fell apart. “We got divorced back in ’09. She got my house. She got my yacht. I had a quarter-million-dollar slot-machine collection. She got everything. I ended up in a homeless shelter. I tried committing suicide. She probably got a boyfriend, this fat, ugly drunken bum. What I got was girls half my age: models, drop-dead gorgeous, gold-digger types.” Just like Donald Trump, I remark. “Yeah,” Donald Junior says, “he likes those.”

This was not the whole story of how he became Trump. He would tell me that later. As with the real Trump, it was difficult to know how much to believe, truth blending easily with fiction, though there are some records on the Internet that suggest he once held a trademark for Super Glue International. Following him around, I found that a lot of Trump supporters had hard-luck stories. In New Hampshire, for instance, I met Linda Hall, a thin woman in her fifties with peroxided hair the same shade as Donald’s (both of them). In a rasping two-pack-a-day voice, she told me that she was born in New Hampshire but went to Texas when she was eighteen, “and after I got kidnapped. . . . Oh yeah. I was kidnapped. They put a great big gun in my mouth. I was sold for three hundred dollars. They told me I was going to Mexico, to a private island with Doberman pinschers. They said, ‘You cooperate or else they’ll make you suffer. You’ll never get off the island, ever.’ I called the police. They couldn’t do anything. They told me that somebody runs Texas and everyone has to go by whoever’s running Texas. The only thing the cop could do was take me to the border line, and I took off for Florida.”

She spent thirty-five years in Florida, but after her marriage went bad she returned to New Hampshire. One daughter was taken into custody by the state; another daughter was in a methadone clinic. She’d had a tragic life, but when Donald Junior came over to talk politics, she got to what was really worrying her. “ISIS is in every frickin’ state right now,” she said. “Oh yeah, every state. I’ve heard that most of the people who are running Florida . . . a lot of them are part of ISIS.” She cocked her head in the direction of Littleton, her hometown. “Littleton’s an easy target. They’re already here. Oh yeah. They buy a place and then they buy like five houses right there. The families are moving in. And they don’t rent out to normal people like us. Some of them are running the stores.”

She was talking about the Lebanese-owned shop nearby, which had been there, a sign proudly proclaimed, for forty years. But Linda said she slept with a gun under her pillow, a .38 with hollow-point bullets, and that she’d bought a .45 for her eighty-two-year-old mother. She also had a ten-year supply of canned goods in her basement, ready, she said, for when President Obama left office. “I guess that’s when it’s all gonna blow. Stores are gonna be wiped out. Everyone I know, they all got weapons. They’re all stocked on food. You got to protect yourself . . . me and Mom. All our friends are saying, load up with plenty of ammunition, because after the stores don’t have no food they’re gonna be hitting houses. They’re going to take over America, put their flag on the Capitol.” “Who?” I asked. “ISIS. Oh yeah.”

Trump’s supporters believe that he is the only one “out there telling the real story” about the Islamic State, as a Florida man named Richard Sherman told me. He was retired, in his sixties, wearing white shorts and a white cutoff T-shirt that called for jihadists to be fed to pigs. “I designed it myself,” he said. “Every time we kill a jihadist, we should chop him up on the White House lawn, on worldwide television, and have pigs eat him. They like to chop off heads. You have to treat terror with terror. That’s the only thing they understand. The Koran tells them to kill Jews, kill Christians, to die in the process, and they will get seventy-two virgins. Okay, we can say: ‘You’re going to be eaten and excreted by pigs. Do you want that?’ If you can get the seventy-two virgins after that, God bless you.”

Of the race for the Republican nomination, he said, “We’re tired of the people who say they’re against Obama and then they do everything Obama wants. The Muslims are slaughtering us — in San Bernardino, in Boston, in Chattanooga. They’re coming to this country and slaughtering us. The immigration people are not keeping them out. All you’re finding is dead Americans all over America. We want somebody who’s going to stop that.”

As we drove around Florida, Trump Junior offered his services to negotiate a peace deal with the Islamic State. There was no limit to what he could do for the Trump campaign, he said, though he was forced to acknowledge that his role was unofficial. He told me he had written about the Islamic State on his website. The address — donaldtrumpjunior.com — was on the side of his limo, right above a large presidential seal, the use of which was possibly illegal. People leaned out of passing vehicles to take pictures as we made stately progress up the highway. He told me that everyone loved the car, and he never paid for tolls. I soon knew why. The toll collector refused Donald’s proffered million-dollar note, and I paid the $1.75. We did, however, get free fried-alligator nuggets at the gas station. The manager, a woman from Bombay, had fond memories of being a croupier in a Trump casino.

The limo was one part of a larger mystery. How was he paying for all this? The last time I had seen him, a few months earlier in New Hampshire, he was flat broke. Now, in addition to the limo, he had a huge SUV, onto which he had stuck more Trump decals and, on the rear, a notice that warned, secret service. stay 100 ft back. machine guns on board! There were several other vehicles, including a Trump-branded Jet Ski, and a new Florida home, a trailer on the shores of Lake Okeechobee. His former wife had the same questions. “Last time I talked to my ex-wife she said, ‘You’re fucking broke. You couldn’t buy a cheeseburger. You asked me for two dollars. And now you’re driving around in fancy cars? Where’d you get the money?’ ”

The explanation might have come from the real Trump’s own lips. “Once you’ve been there, it’s not that hard getting back. After you’ve been a millionaire, you know a lot of people, you have a lot of friends, a lot of contacts. You just put it all together and do it again. My whole life is amazing. Everything about my life is just a nonstop thrill ride on a roller coaster.” The real Trump had managed to conjure even greater wealth out of even greater debt, his companies bankrupted four times. If Donald Junior was living a fantasy, so was Trump himself, just one in which reality had, improbably, aligned with his imagination.

The first Trump rally I saw was in Sioux City, Iowa, the very definition of flyover country. It was in a beautiful old theater with red velvet curtains and ornate plasterwork. Trump’s family were with him, his entourage a row of Saks Fifth Avenue at the front of a hall full of Walmart. It was as if they had been beamed there from another planet, which they had (Manhattan).

People had come to see a TV character called the Donald, a two-fisted billionaire, a pirate Robin Hood, and that is what they got. His speech, as usual, was all about winning, winning, and more winning:

We don’t win anymore. Our country doesn’t win. We used to win. We used to win plenty. . . . Oh, we’re gonna win. We’re gonna win so much, you’re going to get so tired of winning. We’re gonna win. We’re gonna keep winning.

On trade. On health care. On the military. The Islamic State. Mexico. China:

It’s true. It’s true. We’re gonna keep winning. You’re going to say, “Mr. President, please, please, we can’t stand it, we’re winning too much.” I’m gonna say, “I’m sorry. I’m not changing a thing. We’re gonna keep winning.”

A member of Mar-a-Lago, Donald Trump’s private club in Palm Beach, at the club’s party the evening of the Florida primary; revelers outside the ballroom where Trump gave his victory speech

It was what the audience needed to hear. They were sick of losing. “I’ll be honest,” said Randal Thom, a former Marine in his fifties, “I made bad choices.” The bad choices included doing a lot of cocaine. “I attempted suicide prior to getting locked up, but God saved my life.” His T-shirt had a dozen different images of Trump’s head; the effect was of a bunch of Trump balloons. He had driven 120 miles from Minnesota to be here in Iowa at this, his fourth Trump event. I spoke to him while Elton John’s “Rocket Man” blasted from the speakers, one of the songs on a playlist personally selected by Trump for his rallies. Randal found he ran out of money before the end of each month. “I got a felony record [for cocaine possession],” he said ruefully, “and with a felony record it’s hard to get a job nowadays.”

The story of Trump Junior’s own problems with the law was, predictably, more baroque. It was also the story of how he became Trump. Don, as he called himself, liked to use the rallies to try to pick up women. He approached one target, and when he found out she was originally from New Jersey, he said, “Oh, you’ll have heard of the Atlantic City casino bombing, then?” Surprisingly, she had. “That was me!” Trump Junior said, delighted. To understand what happened in Atlantic City, he explained to me, you had to go back to the 1970s, when he was a young man in Boston, selling fireworks for the Mob. (Fireworks were — and are — illegal in Massachusetts.)

“I was just a salesman. I don’t do nothin’ illegal. . . . They used to hijack freakin’ tractor-trailers, okay? They used to do all kinds of shit. The stuff that I saw was fucking incredible.” One day he saw a body in the alley out back. “I was coming home a nervous, shaking wreck. I said to my wife, ‘I’m gonna get killed.’ She says, ‘Of course you are, you fucking idiot.’ ”

He got out. Fast-forward to Atlantic City, 2012, where he had gone to play poker “semi-professionally.” He was in his swimming trunks by the pool, enjoying a beer, when someone from his old life came up to him. “He says, ‘You’re not wearing a wire, are you?’ And I say, ‘No, I’m in a bathing suit.’ Idiot!” The man wanted Gary to come to work for organized crime. Gary refused. “He says, ‘You live in your parents’ basement; you’re driving a shitbox around.’ I go, ‘Yeah, but I’m still alive.’ And then he started getting pissy.”

The Mob wouldn’t take no for an answer. Then the DEA and the chief of the New Jersey State Police approached Gary for help in investigating the man who’d spoken to him. It was all too much. Two days later, he went to the casino to play cards, “all of a sudden the alarms go off. Someone shouts, ‘There’s a bomb.’ I said, ‘Holy shit! I’m getting out of here.’ I walked out, six cops jumped me. I was arrested for trying to blow up a casino. I was the next 9/11. It made worldwide news.”

He went on: “These Mob guys, they’re very powerful. If they don’t get what they want, they’ll make your life miserable. They knew I was coming to Atlantic City. They had time to get the media and everybody else set up for this thing.” A local newspaper did carry this story, in April 2012: “Hundreds of people were briefly evacuated from the Atlantic Club Casino Hotel on Friday afternoon after reports of a bomb threat. A man walked up to a casino floor person, handed her a briefcase and said it was a bomb. The alleged bomb turned out to be a laptop. The man is in police custody.”

He was given Ativan. “They drugged me so I could not walk. They wouldn’t get me a bed, so I slept on the concrete floor. I went to prison and I didn’t do a damn thing. That pretty much ruined my life as Gary Shipko.” So he decided to leave Shipko behind and become Trump. “Shipko is dead. He’s gone. I decided, I’m gonna do this for Donald, but it’s a blast. I get free rooms, free meals, all the little perks, I get free coffees at Burger King. It’s a lot of fun. It really was the right thing to do. I just don’t know how it’s gonna turn out in the end.”

Many of the people at Trump’s events were looking to escape the circumstances of their lives. But they were also looking to Trump for serious answers to their problems. At a rally in the New Hampshire town of Portsmouth, I ran into Dave Kendall, a short, beefy guy holding a large make america great again sign. The warm-up music was the Stones, “You Can’t Always Get What You Want.” Though long past retirement age, he still worked a sixty-hour week, as a tractor salesman. “I can’t retire. I don’t have enough. I cannot ever retire. I just live week to week, month to month. I haven’t got two hundred bucks in my checking. There’s not a lot of brilliant in it, ya know. It’s just a struggle.”

He liked Trump because he thought he would raise Social Security payments, though Trump has made no such promise. “Without that, I cannot survive,” Dave said. “He’s the only guy capable of doing what needs to be done. I like his stand on the immigration. He’ll stop letting all these countries bully us. It’s time to say, ‘No more,’ ya know. I’m seventy-three years old. No one’s taking care of me, I’ll tell ya.”

Members of Mar-a-Lago walking along the club’s lawn; a portrait of Donald Trump, painted by Ralph Wolfe Cowan, hanging in a bar inside the club

In the past, he had voted Democrat. His girlfriend, Kathy Manita, had done the same. She was sitting in the bleachers leaning on a cane “because my legs are so bad. Both my knees are blown.” When I asked her how old she was, she replied, “That’s like asking me how much I weigh. You’re a bad boy.” I asked how she had voted in 2012. There was a long pause. “I’m ashamed to say.” I asked her if she voted for President Obama, and she admitted it. She sounded wretched. Dave broke in to say that the only other candidate who appealed to him was Bernie Sanders, “but I don’t believe he’s got a chance. . . . Trump’s going to bury them all. He’s gonna win because he’s the alternative to everything, he’s smart, and he’s not a politician.”

Such is Trump’s crossover appeal that you often meet people at his rallies whose second choice would be Sanders. At the sports arena in Manchester, New Hampshire, I spoke to Mark Schrepfer, a young man in a red plaid shirt who told me that he was leaning precisely 57 percent to Trump, 43 percent to Sanders. “I was with my fiancée, we’re together right now, and I went to go see Bernie Sanders with her, and he said a lot of good things. He supports the lower class. I’m part of the lower class.” But, he went on, “I’m also a businessman. I’m about money. You know what: in the future, it’s going to help me.”

Mark told me the familiar Trump supporter’s story of misfortune. “My family kicked me out. My dad wanted to teach me a lesson, to show me what a workingman’s supposed to do instead of begging for his money. I was homeless for six months. And you know what I did? I worked. I worked and I never took from the government.” His business is buying steaks from a wholesaler and selling them “out of the back of a truck. Meat. All I need from this guy here is to get me in a better spot than I’m in right now. This Obamacare has got to go. I’m paying six hundred dollars, but I don’t want health insurance. They’re making us have health insurance. I don’t want that. . . . You know what, take the unnecessary out of this country. . . . All the illegal immigrants, they need to leave. We have no problem with you if you can come in this country legally, maybe we could do something. Speak a little bit of English!”

Opinion polls show that most voters don’t care that much about immigration. It usually ranks fourth or fifth when people are asked to name the most important problem facing the country. But there is a segment of Trump supporters for whom it is the only issue. That demographic, a media strategist told me, is “increasingly sixty-year-old-plus white guys.” Outside the Republican debate in Miami in early March was Jack Oliver, a Trump supporter from a group called Floridians for Immigration Enforcement. He was convinced that this would be the issue to determine the outcome of the race in the state.

He wore shorts and a lurid pink T-shirt that said pink-slip rubio. Getting rid of Marco Rubio was an obsession for Jack even before Donald Trump came along. “I got involved in this because I got tired of hearing illegal aliens were just doing jobs Americans wouldn’t do. All the while, I’m seeing my family’s income totally decimated. My family went from having a good middle-class income to just barely getting by — because of illegal labor. And that’s happened to millions of Americans.”

Donald Trump Junior at a Trump rally at the Sunset Cove Amphitheater in Boca Raton, Florida, on March 13; Trump supporters at the rally

Now sixty-five, he had spent most of his working life installing drywall. “Working people in America haven’t had a raise in about forty years. When I first moved to Florida, most of the drywall was union, so we had union benefits, paid vacations, hospitalization, and all that. As illegal labor started taking over, things went non-union, and then the contractors could just tell you, ‘Hey, this is what we’re offering. If you don’t like it, I got ten other guys.’ ” He left Florida in the Eighties because of illegal immigration. “We moved to upstate New York. I was only there about six years. They started bringing busloads, literally busloads, of illegal-alien labor. I saw my income drop thirty-five percent. We moved to Nashville, Tennessee. Same thing: all the drywall contractors start bringing in illegal aliens, and the wages go down again.”

“I came back here to work for this company,” he went on. “We had people from all over South America: Paraguay, Uruguay, Brazil, Costa Rica, Honduras, and then Mexico. It was like an international village. They were from Europe, every place.” But, he went on, “the people replacing Americans, they’re not making enough money either, so they get on public assistance. This little town I lived in, large Guatemalan community there. I’d go into a grocery store, ninety-five percent of them were using food stamps. I look at their cart and I look at mine, they’re eating better than I am.”

Trump — incredibly — has some Hispanic supporters. Behind Jack a clump of photographers were snapping away at a pretty woman in tiny shorts holding a latinos voten por trump sign. Posing with some sparkly pom-poms, she told me that her name was Jessica Leon, that she was of Cuban descent, and that she had worked as a receptionist at the spa in one of Trump’s Miami hotels. “I was hired by him. He’s not a racist at all,” she said. “He’s a person that definitely takes care of his people, his employees, and I think he’ll do the same for this country. The immigration process should be fair. If you make a line and someone cuts you off in the line you get upset, right?”

Another supporter was holding up a pink-slip rubio sign, grinning as passing cars honked. Vladimir Arauz was from Nicaragua. His father, a Sandinista, had named all five of his children after Communist heroes; Vladimir, obviously, after Lenin. He had come to the United States to study at the University of Miami and now worked in the family grocery store. “I had to naturalize. Go through the process,” he said. His friends thought he was crazy for supporting Trump, and he had agonized after Trump announced that Mexican immigrants were rapists. “When he gave the speech about Hispanics . . . I had to make a real hard decision. But if I’m an American, I have to think as an American. If I am an American, that’s the guy that I have to choose.”

Jack Oliver, who was listening, added, “If it wasn’t for Donald Trump, we wouldn’t even be talking about immigration. That’s the last thing the Republican Party wants to be talking about. That’s the last thing a Democrat wants to be talking about. But it is something that the American public has been longing to talk about. That’s why Donald Trump has got such a wide base of support.”

When it came to immigration, Trump Junior’s views were even harsher than his hero’s. One of his beloved Trumpmobiles had been totaled by an illegal immigrant from Mexico, he told me. “On the Mexicans, you gotta do something serious. I mean, a wall, I don’t think that’s gonna happen. But prison, maybe. You know, I think that’s a good idea. Build a real miserable, rotten, giant prison in Arizona, out in the desert. Stick them in there and make them suffer. They have no rights to anything.” This suggestion has yet to be taken up by Trump. But Junior said he had been regularly sending advice to the campaign — and there was evidence that his advice was being listened to by the man himself.

We spoke as we waited in line to get into a Trump event in an amphitheater in Boca Raton. Junior said the advice started last April, when he told Trump to run for president — predicting that he would do so and win. “I’ve been a psychic since I was thirteen. I said never, ever has one of my dreams not come true.” Trump’s usual event playlist boomed from loudspeakers. A protester in a giant penis costume and a Trump mask hovered in the parking lot. Junior said he had told Trump to ease up on women. He did it. Junior even told Trump to ease up on the language about Mexicans. He did that too. Junior paused for a moment to tell a pretty woman: “I’m Donald Trump Junior.” His son? “No, his cousin.” “I’m with the campaign,” he told a Secret Service man. Junior said that by May of last year he had already bought himself a Trump vanity plate and had trump 2016 bumper stickers printed. Trump announced his candidacy the following month.

“He announced it June sixth or something like that. I wrote the letter in May. I said: ‘Donald, if I didn’t know you were gonna be running for president, how did I get all this stuff before you even said you were gonna do it?’ It’s just very, very strange. Why is he doing what he’s doing? He’s doing everything I tell him. It’s amazing, it’s mind-blowing.” Trump Junior decided he would do more than anyone to help Donald J. Trump get to the White House.

He went to one event in Rochester, New Hampshire, last September to offer his help in person. “I get out of my car, I walk down the damn barricades, and people are shaking my hand, then wanting pictures of me. A Trump campaign guy comes over. He says, ‘Holy shit! You get a bigger welcome than Donald himself!’ I said, ‘Well, it’s the car, and people like a gallant personality.’ ” Then the real Trump started walking along, shaking hands. It was a moment that would sow the seeds of a crisis for Junior. Trump came up to Trump Junior, and quite deliberately, it seemed, turned away, moving down the line of proffered hands. “He would not look at me. I tried to make eye contact. I thought, ‘What the fuck is going on?’ Then he passed right by me.”

Junior was stunned, quivering, but he thought there had to be some explanation. He pondered for a long time, the doubts and questions multiplying. Finally, he wrote to Trump that he would come to see him again. There was a news conference in March at Trump’s Florida residence and club, Mar-a-Lago. Junior drove his limo up the long driveway to the club and was stopped near the checkpoint at the top. “I’m with the campaign,” he said. He told me what happened next. “Two cops were there. They said, ‘You don’t work for Donald!’ I said, ‘Yeah, I do!’ They said, ‘No, you don’t. Now get outta here!’ ” Getting the bum’s rush a second time, he went back to his trailer and made a pile of every last thing he owned that bore the name Trump: the vanity plate, the T-shirts, buttons, bumper stickers, signs, and hats, all designed by him and made at his expense. He peeled the decals off the cars and ripped the signs in two. Then he doused the pile in gasoline and watched it go up in flames.

On March 15, the day of the Florida primary, Trump was so confident of victory that he scheduled a huge party at Mar-a-Lago, to begin as the polls were closing. A few journalists were being allowed onto the premises, and I was among them. I knew from having gone to a news conference there before that security would be tight, reporters corralled behind a rope line. The valets toiled to direct a stream of Bentleys, Ferraris, Maseratis, Benzs, and Jaguars to the far end of an immaculate emerald-green lawn. Trump’s guests were gathered around the pool, which shimmered a luminescent turquoise in the dark. Laughter mingled with the sound of clinking glasses. I walked up to the buildings, but instead of turning right, to the security check for the press, I turned left, walked through the service entrance to the spa, and emerged by the pool in the middle of the party. I grabbed a glass of Trump’s champagne from a passing waiter and set about mingling.

I knew this was a risk. I had been at a Trump rally when he called on supporters to “knock the crap” out of an uninvited protester and said he would cover the legal fees. One word from him here and I might disappear in a whirlwind of Jimmy Choos and Stubbs & Wootton velvet loafers. But it was worth it to see a place that Trump boasts is “one of the most highly regarded private clubs in the world.” Only 500 members are allowed, by order of the local council. It costs $100,000 to join and then $14,000 a year after that.

Mar-a-Lago was built in the 1920s by the cereal heiress Marjorie Merriweather Post, then one of America’s richest women. It is all turrets and arches, terra-cotta tiles and stucco, everything in pastel shades. The Palm Beach style is the architectural expression of an ethos that, according to a local journalist, has even led the town to perfume the sewers with lilac and honeysuckle fragrances.

Trump himself, a walking offense against good taste, was not going to be restrained by this ethos. On the front lawn was his legendary flagpole. He had originally made it twice as high as local bylaws allowed, the flag some fifteen times as big. The council fined him. He sued them. A local judge brokered a deal, and Trump agreed to make the eighty-foot pole ten feet shorter. This he did, but then, according to club lore, he brought in bulldozers to construct a mound and stuck the slightly shorter flagpole on top. The huge flag rippled lazily as I left the lawn to enter the library.

There, a portrait of a young, flaxen-haired Trump in tennis whites gazed down. The light seemed to catch his left hand, reflecting brightly. The story of this picture, as told to me by one of the club members, is that the artist rushed the last bit of the painting, the left hand, because Trump tried to get out of paying the $20,000 fee.

Farther on, both the men’s-room door and the paper towels inside had Trump’s crest emblazoned in gold. Actually, it was the Mar-a-Lago crest, to which Trump had added his name, over local protests. On one wall was Trump’s 1990 Playboy cover and a photo of himself jogging through Manhattan in a white tracksuit, carrying the Olympic flame.

Waiting in line to get into the grand ballroom, where Trump was to make his speech, I met an investment banker, a hedge-fund manager, someone in private equity: the new Palm Beach money for which Trump is the brash standard-bearer. A bow-tied financier told me that Mar-a-Lago was not even in the Social Index, the little black book that helps Palm Beach distinguish U from non-U, as the British upper-middle classes used to say. The various charity balls at Mar-a-Lago raised tens of millions, he said, but the club was far from the most exclusive on the island; that honor belonged to the Everglades Club, I was informed. One member named Connie told me that Trump had offended the old Wasp elite in Palm Beach by letting anyone join his club if they had the money. “He was very open. There was no criteria with regard to your background, your ethnicity.” Another member, an Italian count named Guido Lombardi, said: “You have lots of black members. You have a tremendous amount of Jewish members.”

Inside the ballroom — almost the size of a football field and glittering with mirrors, immense chandeliers, and a generous covering of gold leaf — huge TVs showed a shaken-looking Marco Rubio conceding. At the back of the room, a seething mass of journalists were crammed in behind a red velvet rope, watched by dark-suited men with earpieces. Everyone stood for a prayer by a televangelist named Mark Burns. “Father God, in the name of Jesus, I thank you so much for the life of Donald Trump. . . . I’ve been so blessed to . . . see how Donald Trump is uniting the people of this country. It saddens me how the liberal media does a great job in trying to divide us.”

Onstage, Trump himself got a huge cheer when he complained about the “truly disgusting reporters” he had to put up with on the campaign trail. He said he was going to have to explain “basic physics, basic mathematics, basic whatever you want to call it” to some TV commentators who had pointed out that he did not always get a clear majority in the polls. “We have four people [in the race], do you understand that?” There were a few new riffs, but it was the usual Trump shtick: People treat us like dummies. They treat us like fools. Mexico. China. Vietnam! That’s gonna stop. Trump has been called the latest example of the “paranoid style” in American politics (a term popularized by the political scientist Richard Hofstadter in this magazine in 1964). But he does not argue that he is fighting a secret cabal, a conspiracy behind closed doors; he’s saying that he knows the cabal all too well, and they’re stupid, incompetent, a bunch of mooks! What’s needed is a tough guy, a real negotiator, who can take over.

A large, happy crowd gathered after the speech at the club’s bar, the men sporting jackets of pink linen or mauve cashmere, the women covered in expensive jewelry. Everyone seemed to know Trump, and everyone had an opinion. I mentioned a couple of uncomplimentary stories I had heard about Trump before coming to Mar-a-Lago. One was that Trump had thrown a plate of food to the floor, like a toddler, when he didn’t like the taste. And a woman had told me she was deeply offended when Trump told a dirty joke at an event he hosted for female entrepreneurs; she had taken her eleven-year-old daughter, and Trump had used the f-word.

“Oh no, the f-word is merely for the media.”

“He’s a man with a few personalities.”

“There’s the Donald we know — and the brash Donald.”

“Trump’s going to take Palm Beach, and he’s sued everyone here!”

“Until last year, you couldn’t even shake his hand. He doesn’t like to.”

“He has a little phobia about microbes.”

“If he runs this country like he runs this club, it will be a dream come true.”

“I’m not walking to the car. These are two-thousand-dollar shoes.”

Trump stopped by briefly on his way out. “Donald! Best press conference ever!” shouted a short man with a comb-over and a puce jacket. Trump ignored him. He said hello to a retired plastic surgeon named Eli who was his occasional golf partner. The man was Jewish and agreed with most everything Trump said except his comments on immigration. “I have a different point of view. I’m an immigrant. I was born in Europe in a displaced-persons camp after World War Two.” But he went on: “He’s an amazing man . . . a real leader. I feel what we need more than anything is leadership.”

Immigration, or specifically immigrant labor, was not really a concern for those at the party (and indeed the staff serving us were Eastern European and South African). Their main worry was Muslims. One of those at the bar — too worried about “reprisals” to be identified — said, “You hear they’re trying to put in sharia law in Tennessee? Nobody assimilates the Muslims. Nobody. They think in terms of hundreds of years — and they’re winning.” I would hear more of this at Mar-a-Lago.

The next morning, I went to lunch at Mar-a-Lago, this time as an official guest of Count Guido Lombardi, though there was a little unpleasantness at the door, where a couple of surly attendants in shorts hassled our photographer and told him to leave his camera behind. The place looked just as splendid in daylight. Guido and his wife maintained that they were the very first members of Mar-a-Lago when it opened its doors. He said he had known Trump in business, socially, and now in politics for thirty years.

Guido’s shirt was unbuttoned, he was wearing a huge gold belt buckle, but he had a certain louche charm. Luckily for us, he also had an aristocrat’s insouciance. Other Trump associates had said they would need to check with the campaign before talking to a reporter, but Guido said he didn’t need permission “from anybody. I can say anything I want to anybody.” As we sat down to lunch, Trump’s sister, Elizabeth, passed by and shot the count a warning look. “You behave yourself,” she said.

A stout woman wearing a swimming cap did arthritic laps in the pool below. A plane flew overhead, briefly drowning out our conversation. Trump has sued the county several times over airport noise. Lombardi said his wife had warned Trump about the airport when he bought Mar-a-Lago, but at least the planes allowed him to knock a few million off the asking price.

Guido spoke with a distinct Italian accent, despite having been in the United States for forty years. He still had a house in Rome, he said, but would never live there again. “I’m trying to sell. I’m trying to get out of Europe. It’s already a mess. I cannot go anywhere without seeing one of those [bearded Muslims]. . . . I’m very worried about England. England is on the verge of some very serious problems. Just like the rest of Europe. We are losing very quickly our identity as a Judeo-Christian civilization. Once that is gone, there’s no going back.”

We had come full circle, back to Linda in New Hampshire, her .38 under her pillow and her stockpile of canned food in the basement. Lombardi gave me a DVD he had helped to produce called Europe’s Last Stand: America’s Final Warning. As the title suggests, it issues a series of dire predictions about a Muslim takeover of Europe, by an enemy both outside and within. The video speaks of “no-go areas” for non-Muslims in European cities, an issue taken up by some of the Republican field, including, sporadically, by Trump. Lombardi said that he and Trump started to talk about these issues nearly a decade ago. “We have many discussions from 2008 until now. Anytime there is some question about what’s going on in Europe, he’ll check with me: ‘Hey, Guido, what do you think about this? What’s going on about that? What’s the truth?’ Because he doesn’t necessarily trust all the stories that come out of the media.”

He went on to tell me that he had been the representative in New York of the Northern League, Italy’s populist, anti-immigrant political party. He was careful to say he was not one of the campaign’s official advisers, just that Trump listened to him. “We’re friends. If there is something, I tell him. . . . I relay to him some of the things that are going on. But, for God’s sake, I have a nice life. I just do some consulting. The guys on the front line, in Europe, that actually go on the stage to say those things, they’re really risking a bullet every fucking day.” Only Trump could save America, he said, as we walked to our cars.

When Trump Junior finally called me again, he had come through his crisis. He had spoken to a friend on the local campaign in New Hampshire who assured him that Trump was seeing his messages. “He absolutely loves your car. He loves what you’re doing. He just can’t acknowledge you — you’re too radical — you’re saying things he can’t. He needs you.” And Trump knew about the bonfire, he said, because the very next day he had received an email from Trump himself. Junior quoted to me from memory. “You’re an incredible supporter. It’s people like you that make this country great. You are making a huge impact on my campaign. Please come to my next event.” I didn’t want to point out to Junior that this email had probably been sent to a lot of people. He was content. “I would love a job working in the White House. I mean I think what I did in superglue — I just changed the whole industry. I turned it around and picked it up, I reconstructed it, and I can do the same with this country, both of us can, two businessmen together. But you know, I’m not a politician, either. Maybe that’s a good thing.”