Discussed in this essay:

Drive Your Plow over the Bones of the Dead, by Olga Tokarczuk. Translated by Antonia Lloyd-Jones. Riverhead Books. 288 pages. $27.

Heaven’s Breath: A Natural History of the Wind, by Lyall Watson. New York Review Books Classics. 400 pages. $18.95.

A Particular Kind of Black Man, by Tope Folarin. Simon and Schuster. 272 pages. $26.

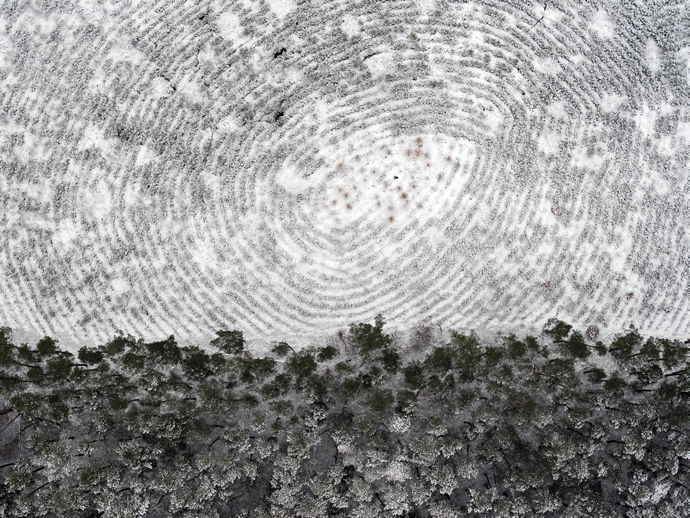

Pomeranian Voivodeship, Poland © Kacper Kowalski/Panos Pictures.

In the lofty Polish hamlet of Luftzug, the skies are low, the winters harsh, and the cell signal perpetually uncertain of its nationality. The highlight of the social calendar is a mushroom-picker’s ball, and the favorite sport of every man from the local playboy to the parish priest is hunting. They do it legally and illegally, alone and in recreational associations, with shotguns and trip-wire snares, and from cross-shaped wooden platforms called pulpits.

Until, that is, they start dying. Neighbors discover a notorious poacher asphyxiated in his cabin; soon after, the body of a police commander turns up at the bottom of a well. Jaded provincial tongues wag. It was the mafia, a smuggling ring, a bad night of poker. Only Janina Duszejko, a retired bridge engineer and vegetarian astrologer in mourning for her vanished dogs, suspects vengeful wildlife.

Beautifully translated by Antonia Lloyd-Jones, Olga Tokarczuk’s Drive Your Plow over the Bones of the Dead (Riverhead Books, $27) is a riveting whodunit with a black-ice surface of fairy-tale charm and a white-hot core of moral fury. The Polish writer is best known for her roving novel Flights, which interleaves the disparate lives of invented travelers with essayistic meditations on airport terminals and the strange migrations of Chopin’s embalmed heart.

Compared with Flights—which Tokarczuk has described as a “constellation” novel for its consonant but non-intersecting storylines—Drive Your Plow’s scope can feel almost picayune. But the novel’s guise of country farce belies a masterpiece of deeper spiritual conflicts. Luftzug’s denizens are every bit as eccentric as the landowners in Gogol’s Dead Souls: an alcoholic dentist who pulls teeth en plein air; a couch-surfing entomologist in search of rare beetle larvae; and an austere lesbian mystery writer who rarely leaves home. The richest man in town is a macho fox farmer with a trophy wife and a long-range rifle who surveys the area in his 4×4, scheming to blast the village into a quarry. Almost every male seems to suffer from “testosterone autism”—or so says Duszejko, Tokarczuk’s narrator, whom chauvinistic locals deride as a “silly old bag.”

Tokarczuk, herself an outspoken vegetarian leftist, is intimately familiar with the abuse heaped on politically radical women of a certain age. In Poland, her books have elicited widespread acclaim, but also outpourings of reactionary vitriol, including death threats for her unsparing depiction of Polish anti-Semitism. When the director Agnieszka Holland adapted Drive Your Plow as Spoor, which won a Silver Bear at the 2017 Berlin Film Festival, the far right denounced it as anti-Catholic and sympathetic to ecoterrorism.

Tokarczuk embraced the charges, jesting that she might include them in the film’s promotional materials; she lends her charismatic protagonist a similar audacity. Her conviction is that killing animals is an abominable crime—during walks around the village each winter, when she takes care of her absent neighbors’ houses, hunters’ platforms remind her of guard towers in a concentration camp. “The eye cut itself on those wooden structures erected in the fields,” Tokarczuk writes. “Isn’t it the height of arrogance, isn’t it a diabolical idea to call a place from which one kills a pulpit?”

Duszejko files complaint after complaint about the town’s laxly enforced hunting laws, ultimately storming the police station with a fistful of bloody bristles from a poached boar. In a climactic scene, she interrupts a sermon in praise of hunters by the local priest, who proceeds to cast her out as though expelling a demon. As the murders continue, her unacknowledged provocations escalate. The fact that nobody bothers to notice old women or the everyday holocaust of animal life turns out to be the novel’s crowning irony.

Duszejko is an acid wit yet a tender observer, with a predilection for nicknames (“Oddball,” “Dizzy”) and a nearly animistic mode of perceiving nature that lends her narrative a fabular charge. In her spare time, she translates William Blake—the novel takes its title, along with a dash of apocalypticism, from his “Proverbs of Hell”—and her gift for metaphor is among the novel’s greatest pleasures. Clouds rub their “wet bellies against the hills.” Rain in floodlights turns to “angel hair on a Christmas tree.” Ailments make one “weak as a potato sprout grown in darkness in the cellar,” while the fungal tendrils of hoarfrost on car windows form a “cosmic mycelium.”

Cosmology is Duszejko’s favorite pastime. Alone through Luftzug’s dark, blustery winters—the hamlet’s name means “current of air”—she computes horoscopes and watches the weatherman, pursuits she imagines uniting in a “Cosmic Impact Channel” of astrological forecasts. Confronting a world racked with human and animal pain, it consoles her to find a moral order in stars and storms, to observe that sometimes “an inexplicable sorrow . . . has just the same character as an atmospheric front, a moody figura serpentinata within the Earth’s atmosphere.”

Landscape with Rain, by Charles E. Burchfield © The Charles E. Burchfield Foundation. From the collection of Merritt P. Dyke.

It’s hard to imagine a better anchorman for the Cosmic Impact Channel than Lyall Watson, a prolific South African writer and naturalist somewhere on the spectrum between crank and polymath. Watson, who died in 2008, was a pith-helmeted intellectual adventurer who produced nature documentaries for the BBC, served as director of the Johannesburg Zoo, and wrote more than twenty books on such subjects as pigs, olfaction, Bali, evil, supernatural occurrences, and the secret lives of inanimate objects.

Among them was Heaven’s Breath: A Natural History of the Wind (New York Review Books Classics, $18.95), a Reagan-era pop-sci bestseller that reads like a lost Renaissance treatise. Half meteorology primer, half treasury of Aeolian arcana, it’s a lyrical-empirical attempt to reconcile what C. P. Snow called the two cultures—science and the humanities—by exploring the wind’s symbolic fecundity in tandem with its earth-shaping force. Creating the sort of reference that novelists might ransack for inspiration, Watson lucidly explains how dunes, cold fronts, and monsoons function; the way that Earth’s rotation warps prevailing winds through the Coriolis effect; a technique to predict bad weather with nothing but a compass and your hands; and the anatomy of a thunderstorm, which “stands on a foot of cool hard rain, with a heel of drizzle and a toe of rolling squall.” The playful coda is a nearly four-hundred-word “Dictionary of Winds,” a lexicon of zephyrs that extends from Morocco’s aajej to Argentina’s zonda.

In the midst of global climate emergency, Watson’s holistic blend of ecology and anthropology—he subscribes to James Lovelock’s Gaia hypothesis, which understands Earth as a self-regulating superorganism—feels less outré than it might have in 1984. It also makes for good reading: physics, folklore, etymology, astronomy, and evolutionary biology conspire in a lively prose that, from discussions of landscape painting to warfare to international commerce, sketches a vivid panorama of the wind’s human history. A gust or gale has occasionally been enough to shift the course of world affairs: in 1281, for instance, a typhoon that came to be known as the kamikaze, or divine wind, wrecked a Mongol fleet invading Japan, providing inspiration to the Second World War’s suicide pilots. Less plausibly, Watson suggests that “ill winds” like the sirocco and Santa Ana might be responsible for everything from traffic accidents in Geneva to murders in Los Angeles.

Caveat lector: Watson asks readers to entertain speculations as to why fish occasionally fall from the sky in downpours and attempts to revive a long-debunked theory called panspermia, which posits that passing comets and solar winds influence genetic variation. These excesses might be inexcusable in a straightforward work of science, but they’re consistent with the book’s attempt to synthesize all the outlandish lore ever produced by our species of “natural wind freaks.”

A touch of madness has always characterized the human aspiration to dominate the atmosphere. Ancient Persians invited breezes by throwing up clouds of saffron, while traditional Inuit storm deterrence relied on jars of urine and seaweed whips. In the 1960s, the U.S. Weather Bureau tried bombing hurricanes with iodide crystals for an experiment called Project Stormfury; with equal efficacy, sixteenth-century sailors attempted to decapitate “water dragon” tornadoes with knives. Herodotus records that a small nation called the Psylli marched into the desert to declare war on the simoom—and were subsequently buried by it. All seem apt parables for contemporary hubris about reengineering the climate.

Heaven’s Breath is most beautiful when it details the airborne migrations of birds, insects, fungal spores, plumed seeds, and microscopic aeroplankton—a concert of life analogous, for Watson, to a planetary nervous system. He rhapsodizes about bugs’ “lacewings, netwings, wings like gossamer, horn, and leather”; the “scimitar perfection” of swallows, evolved for quick maneuvering; and the “gliding aerofoils” of the albatross. Portuguese men-of-war set sail under translucent inflatable bladders, circumnavigating the earth like their namesake ship. But the wind’s most peculiar pilgrims might be ballooning spiders, “arachnauts” who glide on kites of silk over Himalayan peaks.

The Swallow © Private Collection/Look and Learn/Bridgeman Images

No less lonesome than Watson’s mountaineering spiders are the migrants of Tope Folarin’s A Particular Kind of Black Man (Simon and Schuster, $26), a spare and affecting debut novel from the winner of the 2013 Caine Prize for African Writing. It’s a coming-of-age story about Tunde Akinola, a Nigerian boy who moves to suburban Utah with his parents and younger brother in 1981. They want to become Americans, at least the kind they know from Sixties music and TV westerns such as Bonanza and Gunsmoke. Tunde’s father, Segun, chooses Utah because few other Nigerians have heard of it.

It might not have been the best choice. A white schoolmate tries to rub the black off Tunde, while an elderly Mormon neighbor says that if he’s a “good boy,” he can “serve her in heaven.” As his parents chase dreams of a new life and contend with the doldrums of displacement, Tunde spends long days alone, with neighbors, or, for a time, at a YWCA shelter, watching professional wrestling and The People’s Court.

Segun quickly discovers that his engineering degree is as useless as his ten-gallon hat is unfashionable. His marriage implodes when Tunde’s mother develops schizophrenia; after a brief, excruciating custody battle, she returns to Lagos, haunting the rest of the novel like Jane Eyre’s Bertha Mason. Segun remarries, to another divorced Nigerian with two sons who joins the Akinolas in Utah. He pilots this fragile, ever-changing family through a haphazard itinerary of houses, hometowns, and vocations, working odd jobs such as auto mechanic, retail clerk, and ice cream vendor. Segun’s bright determination—exemplified by the hope that his sons will grow up in the mold of Sidney Poitier or Bryant Gumbel—conceals a “sadness . . . so dense and intricate and expansive it should have had its own zipcode.”

Tunde recounts his troubled upbringing with a hypnotic mix of tenderness and analytic detachment. At times recalling Meursault in The Stranger—another displaced loner who loses his mother—he emphasizes the elusiveness of identity for a young immigrant who never stays long in the same place. It’s a story of fits and starts: Tunde daps the fist of belonging when an African-American classmate teaches him a secret handshake; later, at an NAACP event, his heart swells to “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing.” But a move to Texas cuts short this acculturation—at his new high school, the black kids mock his clothes. Nigeria is no substitute; Tunde’s only connection to the country is through long-distance calls with his grandmother, who appears in interstitial dialogues that punctuate the narrative like a transiting comet.

More existential than Afropolitan, Folarin’s novel sharply contrasts with the two best-known novels about African immigrants in the United States, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Americanah and Imbolo Mbue’s Behold the Dreamers. Adichie explores intra-diaspora social divisions at elite universities, while Mbue juxtaposes a white financier’s experience of the 2008 financial crisis with its impact on the family of his Cameroonian driver. Both are worldly bestsellers that take place in the Northeast Corridor and emphasize culture clash; Folarin’s decision to write about a suburban, working-class Nigerian family living farther west—as do growing numbers of Africans, especially in Minnesota and Texas—is refreshing because it portrays the estrangement of immigrants outside the enclaves where new arrivals typically cluster.

Tunde does eventually matriculate at Morehouse, but it’s less a homecoming to what Ta-Nehisi Coates called “Black Mecca” than a catalyst to introspection. Switching from past to present tense, he begins to question his memories, realizing that certain set pieces of his childhood—bonding with his stepmother; his father’s Horatio Alger triumph selling ice cream—have unsuspected shadow sides, or, more distressingly, may simply never have occurred. Tunde begins to fear that he is losing his mind like his mother did. But the onset of “double memories” is also a creative rebirth, a repossession of his narrative from trauma’s repressions and the overbearing dictates of the American dream.

Had Folarin remained in this space of doubt and reckoning, the novel would be significantly stronger. Instead, Tunde has a thinly sketched campus romance with an African-American love interest, which is followed by a prodigal son’s return to Nigeria. It’s hard not to feel cheated by the neat resolution; the book wraps up just as Tunde starts to complicate his parents’ portraits. His admiring yet distant view of Segun—which largely hews to a sunny but quietly suffering immigrant-dad archetype—begins to betray hints of a sharper ambivalence, one that recalls the narrator’s attitude toward his father in V. S. Naipaul’s A House for Mr. Biswas.

What lingers is the image of Segun Akinola behind the wheel of his government-surplus ice cream truck. It’s an old mail carrier with improvised dry-ice freezers, crammed with treats that Tunde and his brothers filch between sales. (Segun regulates their poaching through an “ice cream consumption hierarchy chart.”) At the Hartville City Fair, the truck transforms into a pulpit of immigrant aspiration as Segun leads the Akinolas in prayer: “We are the first ice cream vendors who have been allowed to participate in this festival, O Lord. . . . You have finally given us an opportunity to make it in this country.” But it’s difficult to imagine a more forlorn portrait than, months later, that same truck ferrying the Akinolas to Texas for yet another new beginning. You can’t quite say whether their ark of melting Choco Tacos is a second Mayflower or a satellite knocked adrift.