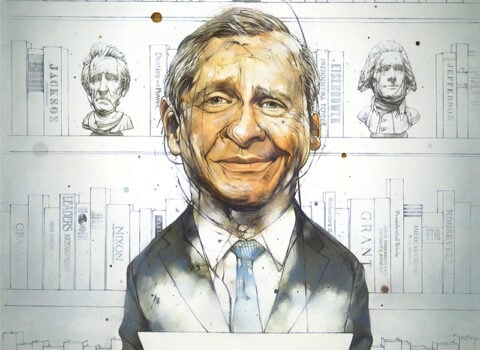

Remember the moment when “the rise of the oceans began to slow and our planet began to heal”? It was late in the spring of 2008, and that was one of the ways Barack Obama described his victory in the Democratic primary race. Enormous crowds greeted him wherever he appeared. Comparisons with Abraham Lincoln were already commonplace; comparisons with Franklin Roosevelt would start shortly thereafter. The senator from Illinois was an almost otherworldly figure, a gifted orator who promised genuine transformation. He would end the era of partisan nit-picking and wedge issues, people thought. He would summon the better angels…

Sign in to access Harper’s Magazine

We've recently updated our website to make signing in easier and more secure

Sign in to Harper's

Hi there.

You have

1

free

article

this month.

Connect to your subscription or subscribe for full access

You've reached your free article limit for this

month.

Connect to your subscription or subscribe for full access

Thanks for being a subscriber!

Get Access to Print and Digital for

$23.99 per year.

Subscribe for Full Access

Subscribe for Full Access