A political virtuoso . . . might write a manifesto suggesting a general assembly at which people should decide upon a rebellion, and it would be so carefully worded that even the censor would let it pass. At the meeting itself he would be able to create the impression that his audience had rebelled, after which they would all go quietly home — having spent a very pleasant evening.

— Kierkegaard, The Present Age

Any summing-up of the Obama presidency is sure to find a major obstacle in the elusiveness of the man. He has spoken more words, perhaps, than any other president; but to an unusual extent, his words and actions float free of each other. He talks with unnerving ease on both sides of an issue: about the desirability, for example, of continuing large-scale investment in fossil fuels. Anyone who voted twice for Obama and was baffled twice by what followed — there must be millions of us — will feel that this president deserves a kind of criticism he has seldom received. Yet we are held back by an admonitory intuition. His predecessor was worse, and his successor most likely will also be worse.

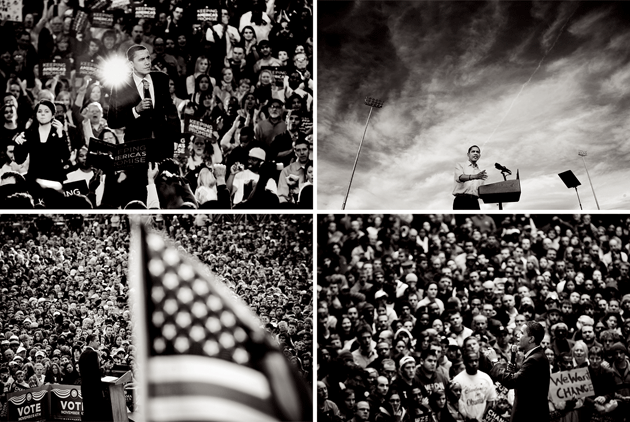

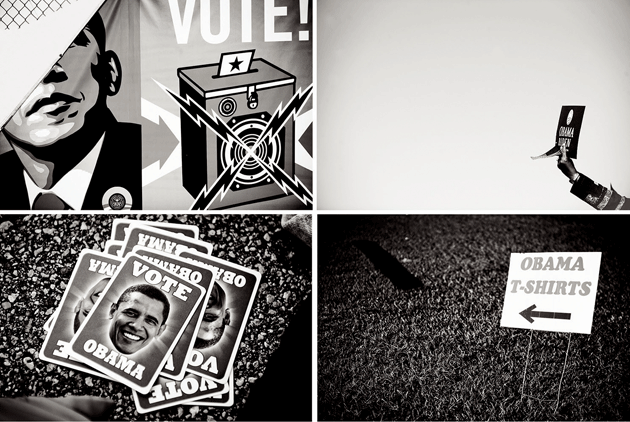

One of the least controversial things you can say about Barack Obama is that he campaigned better than he has governed. The same might be said about Bill Clinton and George W. Bush, but with Obama the contrast is very marked. Governing has no relish for him. Yet he works hard at his public statements, and he wishes his words to have a large effect. Even before he ascended to the presidency, Obama enjoyed the admiration of diverse audiences, especially within black communities and the media. The presidency afforded the ideal platform for creating a permanent class of listeners.

Winning has always been important to Obama: to win and be known as a winner. (Better, in fact, to withdraw from a worthwhile venture than be seen not to succeed.) Alongside this trait, he has exhibited a peculiar avoidance of the business of politics. The pattern was set by the summer of 2009. It came out in the way he shunned the company of his own party, the invitations that didn’t issue from the White House, the phone calls that weren’t made, the curiosity that never showed. Much of politics is a game, and a party leader must enter into the mood of the game; it is something you either do or don’t have an appetite for. Of our recent presidents, only Eisenhower revealed a comparable distaste.

Obama has sometimes talked as if he imagined that, once he moved to the White House, the climb would be in the past. Indeed, some major drawbacks of his first year as president — the slowness in explaining policies and nominating persons to the federal judiciary and other important posts — may be traced to his special understanding of that year’s purpose. It was intended as a time for the country to get to know him. According to a tally published by the CBS correspondent Mark Knoller, the twelve months between January 2009 and January 2010 included 411 occasions for speeches, comments, or remarks by Obama, forty-two news conferences, and 158 interviews. The theory seemed to be that once the public trust was sealed, persuasion and agreement would follow. Mastery of the levers of government was desirable, of course, but it could be postponed to another day.

Meanwhile, Obama’s hesitation in assuming his practical responsibilities was unmistakable; it could be glimpsed at unguarded moments. There was his comment in response to a peevish remark by John McCain during the February 2010 health-care summit, which the president moderated. “Let me just make this point, John,” he said, “because we are not campaigning anymore.” He meant: there are lots of things that we shouldn’t argue about anymore. McCain looked more bewildered than affronted, and his emotion was shared by others who noticed the curt finality of the reply.

Obama meant that the game was over. Now was the time for putting his policies into practice (doubtless with suitable modifications). We had heard enough about those policies during the campaign itself. Postelection, we had left discussion behind and entered the phase of implementation. In the same vein and with the same confidence, he told Republicans on Capitol Hill three days after his inauguration: “You can’t just listen to Rush Limbaugh and get things done.” But they could, and they did. The Republicans had an appetite for politics in its rawest form; for them, the game had barely begun.

To declare the argument over in the midst of a debate is to confess that you are lacking in resources. This defect, a failure to prepare for attacks and a corresponding timidity in self-defense, showed up in a capital instance in 2009. Obama had vowed to order the closure of the prison at Guantánamo Bay as soon as he became president. He did give the order. But as time passed and the prison didn’t close of its own volition, the issue lost a good deal of attraction for him. The lawyer Obama had put in charge of the closure, Greg Craig, was sacked a few months into the job (on the advice, it is said, of Obama’s chief of staff, Rahm Emanuel). Guantánamo had turned into baggage the president didn’t want to carry into the midterm elections. But the change of stance was not merely politic. For Obama, it seemed, a result that failed to materialize after a command had issued from his pen was sapped of its luster.

Yet as recently as March of this year, Obama spoke as if the continued existence of the prison were an accident that bore no relation to his own default. “I thought we had enough consensus where we could do it in a more deliberate fashion,” he said. “But the politics of it got tough, and people got scared by the rhetoric around it. Once that set in, then the path of least resistance was just to leave it open, even though it’s not who we are as a country and it’s used by terrorists around the world to help recruit jihadists.” One may notice a characteristic evasion built in to the grammar of these sentences. “The politics” (abstract noun) “got tough” (nobody can say why) “and people” (all the people?) “got scared” (by whom and with what inevitability?). Adverse circumstances “set in” (impossible to avoid because impossible to define). In short, once the wrong ideas were planted, the president could scarcely have done otherwise.

The crucial phrase is “the path of least resistance.” In March 2015, in the seventh year of his presidency, Barack Obama was presenting himself as a politician who followed the path of least resistance. This is a disturbing confession. It is one thing to know about yourself that in the gravest matters you follow the path of least resistance. It is another thing to say so in public. Obama was affirming that for him there could not possibly be a question of following the path of courageous resistance. He might regret it six years later, but politics set in, and he had to leave Guantánamo open — a symbol of oppression that (by his own account) tarnished the fame of America in the eyes of the world.

It is perhaps understandable that Obama felt a declaration of his intention to close Guantánamo need not be followed by the political work of closing it. For Barack Obama sets great store by words. He understands them as a relevant form of action — almost, at times, a substitute for action. He takes considerable authorial pride in the autobiography he published before becoming a politician. We may accordingly ask what impression his spoken words have made in his presidency, from the significant sample we now possess. He employs a correct and literate diction (compared with George W. Bush) and is a polite and careful talker (compared with Bill Clinton), but by the standard of our national politics Obama is uncomfortable and seldom better than competent in the absence of a script. His show of deliberation often comes across as halting. His explanations lack fluency, detail, and momentum. Take away the script and the suspicion arises that he would rather not be onstage. The exception proves the rule: Obama has a fondness for ceremonial occasions where the gracious quip or the ironic aside may be the order of the day, and he is deft at handling them. As for his mastery in delivering a rehearsed speech, the predecessor he most nearly resembles is Ronald Reagan.

This presents another puzzle. Obama said during the 2008 primaries that he admired Reagan for his ability to change the mood of the country — the ability itself, he meant, abstracted from the actual change Reagan brought. Astonishingly, Obama seems to have believed, on entering the White House, that his power as an interpreter of the American dream was on the order of Reagan’s. But this ambition was less exorbitant than it looked; the differences between their certitudes are small and cosmetic. Reagan spoke of the “shining city on a hill.” Obama says: “I believe in American exceptionalism with every fiber of my being.”

He came into office under the pressure of the financial collapse and the public disenchantment with the conduct of the Bush–Cheney “war on terror.” It has been said that this was an impossible point of departure for our first black president. Might the opposite be true? The possibilities were large because the breakthrough was unheard-of. The country was exhausted by eight years on a crooked path. The nature of the doubt, the nature of the uncertainty, it is possible to think, made the early months of 2009 one of those plastic hours of history when the door to a large transformation swings open. Obama himself evidently saw it that way. On June 3, 2008, having just won the Democratic primaries, he declared in Minnesota that people would look back and say, “This was the moment when the rise of the oceans began to slow, and our planet began to heal.” The language was messianic, but the perception of a crisis and of the opportunity it offered was true.

Obama’s warmest defenders have insisted, against the weight of his own words, that such hopes were absurd and unreal — often giving as evidence some such conversation stopper as “this is a center-right country” or “the American people are racist.” But the same American people elected an African American whose campaign had been center-left. He inherited a majority in both houses of Congress. It takes a refined sense of impossibility to argue that Obama in his first two years actually traveled the length of what was possible.

During Obama’s first year in office, the string of departures from his own stated policy showed the want of connection between his promises and his preparation to lead. The weakness was built-in to the rapid rise that carried him from his late twenties through his early forties. His appreciative, dazzled, and grateful mentors always took the word for the deed. They made the allowance because he cut a brilliant figure. Obama’s ascent was achieved too easily to be answerable for the requirement of performing much. This held true in law school, where he was elected president of the Harvard Law Review without an article to his name, and again in his three terms as an Illinois state senator, where he logged an uncommonly high proportion of noncommittal “present” votes rather than “ayes” or “nays.” Careless journalists have assumed that his time of real commitment goes further back, to his three years as a community organizer in Chicago. But even in that role, Obama was averse to conflict. He was never observed at a scene of disorder, and he had no enemies among the people of importance in the city.

He came to the presidency, then, without having made a notable sacrifice for his views. Difficulty, however — the kind of difficulty Obama steered clear of — can be a sound instructor. Stake out a lonely position and it sharpens the outline of your beliefs. When the action that backs the words is revealed with all its imperfections, the sacrifice will tell the audience something definite and interesting about the actor himself. Barack Obama entered the presidency as an unformed actor in politics.

In responding to the opportunities of his first years in office, Obama displayed the political equivalent of dead nerve endings. When the news broke in March 2009 that executives in AIG’s financial-products division would be receiving huge bonuses while the federal government paid to keep the insurance firm afloat, Obama condemned the bonuses. He also summoned to the White House the CEOs of fifteen big banks. “My administration,” Obama told them, as Ron Suskind reported in Confidence Men, “is the only thing between you and the pitchforks.” But the president went on to say that “I’m not out there to go after you. I’m protecting you.” Obama was signaling that he had no intention of asking them for any dramatic sacrifice. After an embarrassed reconsideration, he announced several months later that he had no use for “fat cats.” But even that safe-sounding disclaimer was turned upside down by his pride in his acquaintance with Lloyd Blankfein, of Goldman Sachs, and Jamie Dimon, of JPMorgan Chase: “I know both those guys; they are very savvy businessmen.” His attempt to correct the abuses of Wall Street by bringing Wall Street into the White House might have passed for prudence if the correctives had been more radical and been explained with a surer touch. But it was Obama’s choice to put Lawrence Summers at the head of his economic team.

In foreign policy, Afghanistan was the first order of business in Obama’s presidency. His options must have appeared exceedingly narrow. During the campaign, he had followed a middle path on America’s wars. He said that Iraq was the wrong war and that Afghanistan was the right one: Bush’s error had been to take his eye off the deeper danger. By early spring of 2009, Obama knew that his judgment — though it earned him praise from the media — had simply been wrong. The U.S. effort in Afghanistan was a shambles, and nobody without a vested interest in the war was saying otherwise.

Two incidents might have been seized on by a leader with an eye for a political opening. The first arrived in the form of diplomatic cables sent to the State Department in early November 2009 by Karl W. Eikenberry, the ambassador to Afghanistan and, before that, the senior commander of U.S. forces there. Eikenberry’s length of service and battlefield experience made him a more widely trusted witness on Afghanistan than General David Petraeus; his cables said that the war could not be won outside the parts of the country already held by U.S. forces. No more troops ought to be added. Eikenberry recommended, instead, the appointment of a commission to investigate the state of the country. Any reasonably adroit politician would have made use of these documents and this moment. With a more-in-sorrow explanation, such a leader could have announced that the findings, from our most reliable observer on the ground, compelled a reappraisal altogether different from the policy that had been anticipated in 2008. Though Obama had his secretary of state, Hillary Clinton; his secretary of defense, Robert Gates; and the chairman of the joint chiefs, Michael Mullen, arrayed against him, he also had opponents of escalation, including Vice President Biden and others, at the heart of his policy team. He chose to do nothing with the cables. A lifeline was tossed to him and he treated it as an embarrassment.

A plainer opportunity came with the killing of Osama bin Laden on May 2, 2011. This operation was the president’s own decision, according to the available accounts, and it must be said that many things about the killing were dubious. It gambled a further erosion of trust with Pakistan, and looked to give a merely symbolic lift to the American mood, since bin Laden was no longer of much importance in the running of Al Qaeda: the terrorist organization was atomized into a hundred splinter groups in a dozen countries. The temporary boost to patriotic morale that came from this spectacular revenge may also have influenced Americans to accept more casually the legitimacy of assassinations.

That he killed the instigator of the September 11 attacks surely helped Obama to win reelection in 2012. With a larger good in view, he might also and very plausibly have used the death of bin Laden as an occasion for ending the occupation of Afghanistan. If the Eikenberry cables afforded a chance to tell the unpopular truth no politician wants to utter — “We can’t win the war” — the death of bin Laden offered a prime opportunity to recite a comforting fiction to the same effect: “Al Qaeda is our enemy. It is now a greatly diminished force, and we have killed its leader. At last, after so much pain and sacrifice, we can begin to wind down the war on terror.”

But Obama made no such gesture. He held on to his December 2009 plan, which had called for an immediate escalation in Afghanistan to be followed by de-escalation on a clock arbitrarily set eighteen months in advance. The days after the killing saw the White House inflating and deflating its accounts of what happened in Abbottabad, while Obama himself paid a visit to SEAL Team 6. A truth about the uses of time in politics — as Machiavelli taught indelibly — is that the occasion for turning fortune your way is unlikely to occur on schedule. The delay in withdrawing from Afghanistan was decisive and fatal, and it is now a certainty that we will have a substantial military presence in that country at the end of Obama’s second term.

Much of the disarray in foreign policy was inevitable once Obama resolved that his would be a “team of rivals.” The phrase comes from the title of Doris Kearns Goodwin’s book about the Civil War cabinet headed by President Lincoln. To a suggestible reader, the team-of-rivals conceit might be taken to imply that Lincoln presided in the role of moderator; that he listened without prejudice to the radical William Seward, his secretary of state, and the conservative Montgomery Blair, his postmaster general; that he heard them debate the finer points of strategy and adjudicated between them. Actually, however, Goodwin’s book tells a traditional (and true) story of Lincoln as a leader, both inside the cabinet and out.

The idea of a team of rivals stuck in Obama’s mind because it suited his temperament. But the cabinet he formed in 2009 involved a far more drastic accommodation than any precedent can explain. Obama hoped to disarm all criticism preemptively. He had run against Hillary Clinton — who did lasting damage by saying that he was unqualified to lead in a time of emergency — and he paid her back by putting her in charge of the emergency. For the rest, Obama selected persons of conventional views, largely opposed to his own and in some cases opposed to one another. It was an unorganized team, perhaps not a team at all, but that hardly mattered. The Cabinet met nineteen times during his first term, an average of only once every eleven weeks.

The largest issues on which Obama won the Democratic nomination were his opposition to the Iraq war and his stand against warrantless domestic spying. He had vowed to filibuster any legislation giving immunity to telecommunications companies, and withdrew that pledge (with a vow to keep his eye on the issue) only after he secured the nomination. And yet among all the names in the cabinet there was not one opponent of warrantless surveillance on his domestic team, and, on his foreign-policy team, no one except Obama himself who had spoken out or voted against the Iraq war. (Lincoln, by contrast, placed abolitionists in two critical posts: Seward at State and Salmon Chase at Treasury.) Thus, on all the relevant issues, Obama stood alone; or rather, he would have stood alone if his views had remained steady. His choice not only of cabinet members but of two chief advisers — Summers and Emanuel — could be read as a confession that he was intimidated in advance.

Obama’s foreign policy also revealed a trait he shares with most other Democratic presidents: he considers domestic policy his major responsibility. Foreign policy is a necessary encumbrance; it is a burden to be transferred to other hands. What Democrats have never properly recognized is that for any powerful and expanding state, foreign entanglements set definite limits on what is possible at home. The energy and expenditure that went into wars such as Korea, Vietnam, Afghanistan, and Iraq had broad consequences for domestic benefits as various as social insurance and environmental protection.

Obama’s domestic policy has, for the most part, exhibited a pattern of intimation, postponement, and retreat. The president and his handlers like to call it deliberation. A fairer word would be “dissociation.” Once Obama walks out of a policy discussion, he does not coordinate and does not collaborate. This fact is attested by so many in Congress that it will take a separate history to chronicle the disconnections. He intensely dislikes the rituals of keeping company with lesser lawmakers, even in his own party. Starting with the Affordable Care Act, he has stayed aloof from negotiations, as if recusing himself afforded a certain protection against being blamed for failure. He does not cultivate political friends, or fraternize with comrades. Add to this record his episodic evacuations of causes (global warming between 2010 and 2012; nuclear proliferation between 2011 and 2015) and the activists who got him the nomination in 2008 may be pardoned for wondering what cause Obama ever espoused in earnest.

One of the surprises of reviewing the conception and execution of the Affordable Care Act is that Obama came to the subject late and almost experimentally. In the 2008 primaries, the health-care policies of Hillary Clinton and John Edwards were widely judged to be more comprehensive than Obama’s, and he would later concede he had been wrong to reject the individual mandate. But in the earliest days of the new administration, he tested the popularity of two quite different investments of political capital: health care and climate change. Health care won out. He delegated the responsibility for drafting the measure to five separate committees of Congress and sent his vice president to run interference for many months. No serious speech was given to explain the policy, and how could there be a speech? There wasn’t yet a policy. In the meantime, he suspended engagement with most of the other issues that might be judged important. Between January 2009 and March 2010, health care swallowed everything. Obama did it because he wanted to “do big things,” to have a piece of “signature legislation.”

If he was a cautious president-elect in November 2008, he seemed to be in full retreat by the end of 2010. A few days after the midterm disaster, Obama vowed to carry forward the Bush tax cuts for the richest Americans. When the Republican majority saw weakness so clearly telegraphed, their threat to close the government and their refusal to raise the debt ceiling in 2011 were foreseeable obstructions. The president for his part — as Harry Reid’s chief of staff observed with genuine shock — had no Plan B. Eventually, Obama spun out an improbable compromise. He met the Republican ultimatum with an offer of sequestration of government funds, which would enforce across-the-board budget cuts in the absence of a later deal. This measure was extorted by panic. Obama apparently assumed that the drawbacks in funding for education, food inspection, highway construction, and other essential activities of government would be immediately evident to the American public. It has proved an empty hope. Sequestration will be part of the Obama legacy as much as the Affordable Care Act.

When the Tea Party sprang up in reaction to the Troubled Asset Relief Program and the A.C.A., Obama never mentioned the protest and never sought to refute the movement. Through his first term he barely recognized its existence. Only when pressed would he name the Tea Party, but even then he spoke of the threat to his policies in a vague generic way: the Tea Party represented an age-old tendency in American politics, founded on innocent misunderstanding. There was nothing to be done about it.

This strain of quietism has been a recurrent and uneasy motif of Obama’s presidency. But the trait is deeply rooted. How else to explain his avoidance of meetings with Kathleen Sebelius in the run-up to the launch of the A.C.A.’s insurance exchanges? That a busy president might not ask for a weekly progress report in the year preceding the rollout is understandable. But considering how much the result mattered — not just to his legacy but also to the trust in government he had pledged to restore — what could be the excuse for conversing face- to-face with the secretary of health and human services only once in the three and a half years before the unraveling? The new law is bringing medical care to millions who never before could rely on such protection. In the long run, it is likely to be a tremendous benefit to the society at large. Yet opposition to the reform has never let up.

Given the weight of the moment, it was extraordinarily careless of the president to have allowed its effect to be diluted by a succession of avoidable delays. He also missed the opportunity to supply a single conclusive explanation of the meaning of his reform. Along with his contradictory declarations on Syria, the botched health-care rollout did more than anything else to spoil the first year of Obama’s second term. It scuttled any chance the Democrats may have had for preserving their Senate majority.

Different as the issues have been, Obama’s retreat from controversy in dealing with Guantánamo, his deference to the generals in Afghanistan even when circumstances took his side, and his willingness to cede health care to a complex bureaucratic machine that lacked any competent controls all shared a characteristic signature. His resort to the path of least resistance has been a consistent and almost reflexive response to friendly conditions that turn suddenly hostile. But the hostility in question may be something more than partisan suspicion and rancor.

It now seems clear that during the presidential transition, between November 2008 and January 2009, Obama was effectively drilled in the intricacies of U.S. operations abroad, the secret deployment of special forces, the expansion of domestic spying by the NSA, and the full extent of terror threats both inside and outside the United States (as determined by the high officials of the security apparatus). More than might have been expected from a principled politician, he was set back on his heels. It would be understandable if he was also frightened.

The first visible effect of his reeducation was the speech he gave at the National Archives on May 21, 2009. Whatever might become of Guantánamo itself, the policy Obama laid down at the National Archives ensured that the United States would maintain a category of enemy combatants charged with no specific crime. These prisoners would be as helpless as those whom Bush and Cheney had “rendered” or sent to Guantánamo. The speech defined a category of permanent detainees — their cases impossible to try in court, because the evidence against them had been obtained by torture; their condition now irremediable, because they posed a continuing threat to the United States.

Obama also followed Cheney’s path in keeping much of the war on terror off the books by employing mercenaries — known now by the euphemism “contractors.” He held on to another Cheney innovation when he invoked the state-secrets privilege to undercut legal claims by prisoners seeking redress and citizens invoking the Fourth Amendment protection against searches and seizures. Privilege of this kind is not compatible with the functional necessities of a constitutional democracy.

The right to a fair and speedy trial is guaranteed by the Constitution, as are all the conditions for a relevantly informed discussion of public affairs. In the Obama Administration, however, as in the Bush–Cheney Administration before it, the war on terror was to stand on a different footing. Matters relating to war and domestic security were closed to the scrutiny of the people. The shift in Obama’s attitude between April and June 2009 could not have been more conspicuous. He delivered the National Archives speech in response to many weeks of harsh and testing attacks by the Republican right, and especially by Cheney, who denounced the decision by the new president to publish the torture memos and a second series of Abu Ghraib photographs. When Obama surrendered on these fronts, they knew they had him on the run in Guantánamo, Afghanistan, and elsewhere.

Obama’s expansion of the war on terror was predictable, but at every stage he raised people’s hopes before dashing them. He made waterboarding illegal, together with many other practices of “enhanced interrogation.” This was a brave achievement to which no minus sign can be attached. At the same time, he brought John Brennan into the White House to organize command procedures for drone killings. In the manner of Cheney, Obama kept secret the document establishing the legal rationale for the strikes. By the end of 2014, Obama had ordered 456 drone attacks (compared with fifty-two by Bush). Unhappily, there is truth in the charge by Bush’s supporters that President Obama has spared himself the illegality of torture by killing the suspects whom his predecessor would have kidnapped for “enhanced interrogation.”

In foreign policy across the greater Middle East, Obama’s major concern was to avoid any suggestion of a religious war against Islam. His speech in Cairo on June 4, 2009, was the first step in that direction. His plan to negotiate a State of Palestine was supposed to be the second. In the drawn-out confusion of the Arab Spring, however, he allowed himself to be trapped by the combination of neoconservative advocates of never-ending war, such as Robert Kagan, and liberal believers in humanitarian war, such as Samantha Power and Anne-Marie Slaughter, whose claim to a “responsibility to protect” licensed NATO’s bombing of Libya and the overthrow of Muammar Qaddafi. Obama’s decision to follow their advice has brought anarchy to Libya and made it a depot for jihadists in the region.

The scale of the Libyan disaster was already known when the same advisers and opinion makers knocked on Obama’s door for intervention in Syria. Once again, he had a hard time resisting, and was almost lured into a major bombing attack and an attempt at the overthrow of Bashar al-Assad. Only much later would Obama acknowledge that it was “a fantasy” that the United States could outflank the Islamist rebels by subsidizing an American-vetted moderate force, “essentially an opposition made up of former doctors, farmers, pharmacists and so forth.” The worst feature of the engagements in Libya and Syria has been the president’s refusal of honest explanations to the public. In Libya, this refusal was accompanied by something approaching a denial of responsibility. He has referred most questions regarding Libya to Hillary Clinton’s State Department, but Obama was the president. He approved the no-fly interdiction that shaded into the destruction of a government and wrought a civil war. If the chaos that ensued has added to the horrors of the sectarian conflict in the region, part of the fault lies with Obama. In both Syria and Iraq, a necessary ally in the fight against Sunni fanatics (including the recent incorporation that calls itself the Islamic State) has been the Shiite regime in Iran. Yet Obama has been hampered from explaining this necessity by his extreme and programmatic reticence on the subject of Iran generally.

About the time the last sentence was written, President Obama announced the framework of a nuclear deal between the P5+1 powers and Iran. If he can clear the treaty with Congress and end the state of all but military hostility that has prevailed for nearly four decades between the United States and Iran, the result will stand beside health care as a second major achievement. To bring it off will demand tremendous resourcefulness and a patience as unusual as the impetus that drove the Affordable Care Act. And it will require even greater strength of resolution. An uncompromising personal investment will have to be shown, and will have to persist against fierce opposition. Obama will have to recognize that his most dedicated opponents — the neoconservatives who dictate Republican foreign policy — are relentless and that they will not stop until they are stopped. Nevertheless, a lasting détente with Iran seems possible; what are the obstacles?

Until this moment, Obama has taken care not to disturb the American consensus that Iran is a uniquely dangerous country. He has said and done little to counter the right-wing Israeli propaganda that pictures Iran as the greatest exporter of terrorism in the world. His peace-bearing Ramadan messages to non-fanatical believers in Islam have eluded notice in the American press and made no impact on public opinion. The arrogance of his executive action on Libya, too, left a residual irritation that can now be exploited to throw a cloak of principle over merely partisan or expedient opposition to the nuclear deal. These obstacles can only be resisted by the constant pressure of argument that gives reasons and tirelessly repeats its reasons. A president whose main talent has seemed to be inspiration, not explanation, will have to venture now, very far and very often, into the field of lucid explanation. But Obama today has Europe backing him; and elements of the Israeli intelligence community show signs of breaking away from Netanyahu’s insistence on the posture of war. The result may depend ultimately on the willingness of a few well-placed senators to part with an old enemy whose status has become familiar and almost customary.

A forgotten aspect of the current nuclear negotiations is that they had a precursor. The agreement that Obama hopes to secure was anticipated and turned down by the president himself in May 2010. At that time Turkey and Brazil had offered to receive low-enriched uranium from Iran in return for allowable nuclear fuel and the opening of trade and lifting of sanctions. Why Obama spurned the offer, as Trita Parsi related in A Single Roll of the Dice, remains something of a mystery. It may have been ill suited to domestic politics on the way to a midterm election; and the deal had not been properly coordinated with Russia. Perhaps, too, there was an element of pique: credit for the breakthrough would have been stolen from the American president by two upstart minor powers. Mrs. Clinton also played a significant part in deflecting the Brazil–Turkey proposal.

When such incidents add up to a critical mass, they can no longer be taken as accidents. They tell us something discouraging about the Obama White House and its relation to the State Department. The shortest description of the disorder is that President Obama does not seem to control his foreign policy. A recent and dangerous instance, still unfolding in Ukraine, began in November 2013 and reached its climax in the February 2014 coup that overturned the Yanukovych government. But the coup in Kiev was only the last stage of a decade-long policy of “democracy promotion” that looked to detach Ukraine from Russia. Victoria Nuland, the assistant secretary of state for European and Eurasian affairs, boasted in December 2013 that the United States had spent $5 billion since 1991 in the attempt to convert Ukraine into a Western asset. The later stages of the enterprise called for the defamation of Vladimir Putin, which went into high gear with the 2014 Sochi Olympics and has not yet abated. When Nuland appeared in Kiev to hand out cookies to the anti-Russian protesters, it was as if a Russian operative had arrived to cheer a mass of anti-American protesters in Baja California.

Through the many months of assisted usurpation, no word of reprimand ever issued from President Obama. An intercepted phone call in which Nuland and Geoffrey Pyatt, the ambassador to Ukraine, could be heard picking the leaders of the government they aimed to install after the coup aroused no scandal in the American press. But what could Obama have been thinking? Was he remotely aware of the implications of the crisis — a crisis that plunged Ukraine into a civil war and splintered U.S. diplomacy with Russia in a way that nothing in Obama’s history could lead one to think he wished for? His subsequent statements on the matter have all been delivered in a sedative nudge-language that speaks of measures to change the behavior of a greedy rival power. As in Libya, the evasion of responsibility has been hard to explain. It almost looks as if a cell of the State Department assumed the management of Ukraine policy and the president was helpless to alter their design.

Suppose something of this sort in fact occurred. How new a development would that be? Five months into Obama’s first term, a coup was effected in Honduras with American approval. A lawyer for the businessmen who engineered the coup was the former Clinton special counsel Lanny Davis. Did Obama know about the Honduras coup and endorse it? The answer can only be that he should have known; and yet (as with Ukraine) it seems strange to imagine that he actually approved. It is possible that an echo of both Honduras and Ukraine may be discerned in a recent White House statement enforcing sanctions against certain citizens of Venezuela. The complaint, bizarre on the face of it, is that Venezuela has become an “unusual and extraordinary threat” to the national security of the United States. These latest sanctions look like a correction of the president’s independent success at rapprochement with Cuba — a correction administered by forces inside the government itself that are hostile to the White House’s change of course. Could it be that the coup in Ukraine, on the same pattern, served as a rebuke to Obama’s inaction in Syria? Any progress toward peaceful relations, and away from aggrandizement and hostilities, seems to be countered by a reverse movement, often in the same region, sometimes in the same country. Yet both movements are eventually backed by the president.

The situation is obscure. Obama’s diffidence in the face of actions by the State Department (of which he seems half-aware, or to learn of only after the fact) may suggest that we are seeing again the syndrome that led to the National Archives speech and the decision to escalate the Afghanistan war. Edward Snowden, in an interview published in The Nation in November 2014, seems to have identified the pattern. “The Obama Administration,” he said, “almost appears as though it is afraid of the intelligence community. They’re afraid of death by a thousand cuts . . . leaks and things like that.” John Brennan gave substance to this surmise when he told Charlie Rose recently that the new president, in 2009, “did not have a good deal of experience” in national security, but now “he has gone to school and understands the complexities.” This is not the tone of a public servant talking about his superior. It is the tone of a schoolmaster describing an obedient pupil.

However one reads the evidence, there can be no doubt that Obama’s stance toward the NSA, the CIA, and the intelligence community at large has been the most feckless and unaccountable element of his presidency. Indeed, his gradual adoption of so much of Cheney’s design for a state of permanent emergency should prompt us to reconsider the importance of the Deep State — an entity that is real but difficult to define, about which the writings of James Risen, Mike Lofgren, Dana Priest, William Arkin, Michael Glennon, and others have warned us over the past several years. There is a sense — commonly felt but rarely reflected upon by the American public — in which at critical moments a figure like John Brennan or Victoria Nuland may matter more than the president himself. There could be no surer confirmation of that fact than the frequent inconsequence of the president’s words, or, to put it another way, the embarrassing frequency with which his words are contradicted by subsequent events.

Bureaucracy, by its nature, is impersonal. It lacks an easily traceable collective will. But when a bureaucracy has grown big enough, the sum of its actions may obstruct any attempt by an individual, no matter how powerful and well placed, to counteract its overall drift. The size of our security state may be roughly gauged by the 854,000 Americans who enjoy top-secret security clearances, according to the estimate published by Priest and Arkin in the Washington Post in 2010. The same authors reported that nearly 2,000 private companies and 1,300 government organizations were employed in the fields of counterterrorism, intelligence gathering, mass surveillance, and homeland security.

When Obama entered the White House, it was imperative for him to rid the system of the people who would work against him. Often they would be people far back in the layers of the bureaucracy; and where removal or transfer was impossible, he had to watch them carefully. But in his first six years, there was no sign of an initiative by Obama to reduce the powers that were likeliest to thwart his projects from inside the government. On the contrary, his presumption seems to have been that all the disparate forces of our political moment would flow through him, and that the most discordant tendencies would be improved and elevated by this contact as they continued on their way.

One ought to say the best one can for a presidency that has created its own obstacles but has also been beset by difficulties no one could have anticipated. Obama has governed in a manner that is moderate-minded and expedient. He has been mostly free of the vengeful and petty motives that can derail even a consummate political actor. His administration, the most secretive since that of Richard Nixon, has been the reverse of transparent, but it has also been entirely free of political scandal. There is a melancholy undercurrent to his presidency that recalls Melville’s lines in “The Conflict of Convictions”: “I know a wind in purpose strong — / It spins against the way it drives.”

Though Obama has hardly been a leader strong in purpose, his policies have indeed spun against the way they drove. Nobody bent on mere manipulation would so often and compulsively utter a wish for things he could not carry out. Yet Obama has done little to counteract the regression of constitutional democracy that began with the security policies and the wars of Bush and Cheney. This degeneration has been assisted under his negligent watch, sometimes with his connivance, occasionally by exertions of executive power that he has innovated. Much as one would like to admire a leader so good at showing that he means well, and so earnest in projecting the good intentions of his country as the equivalent of his own, it would be a false consolation to pretend that the years of the Obama presidency have not been a large lost chance.