Art Young would have turned 150 years old this month, and the finest gift we could have given him is Bernie Sanders’s campaign to welcome socialism back into America’s parlor after decades of keeping it chained in the basement. Art Young? He was the greatest radical political cartoonist in our history, a one-of-a-kind American original. His ability to boil complex social issues down to memorable symbols, drawn with justifiable anger but permeated with genial warmth, would be an immeasurable asset to Bernie in explaining the realities of today’s class war to its casualties.

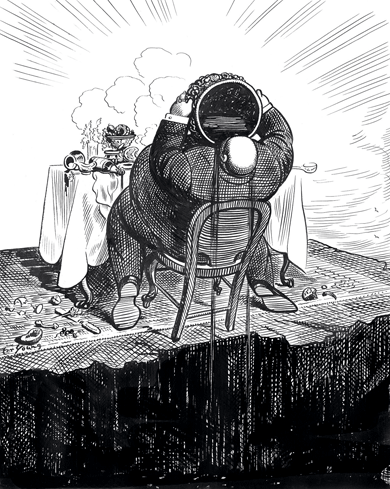

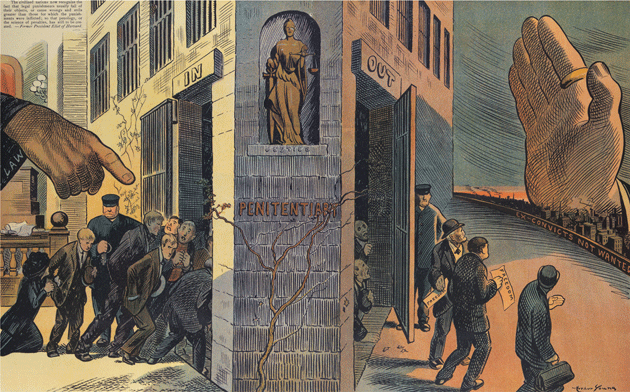

Capitalism and the Reformer, by Art Young, from The Best of Art Young © 1936 The Vanguard Press, Inc., New York City. All artwork by Art Young

Unfortunately, political cartooning, like socialism, has fallen on hard times, and Art Young’s job description no longer really exists: A Radical! Political!! Cartoonist!!! It’s the oblivion trifecta. 1. Radical: We Americans, poor fish, have a perpetually recurring case of amnesia, trying to wriggle off the hook when it comes to facing our history as a Rapacious Capitalist Empire. We prefer to think of ourselves as wide-eyed innocents with perpetually renewing hymens. 2. Political: The word evokes C-SPAN–scale boredom and clouds of toxic rhetoric. The only concept less inviting is “political radical,” which conjures up images of dangerous bomb-throwing anarchists — what could be worse? Oh, I know: 3. Cartoonist! A creator of trivial diversions, only worth the time more fruitfully spent dozing if the creator is (a) hilarious, (b) salacious, or, preferably, (c) both. In fact, one of the few phrases more snooze-worthy than “political” may be “political cartoonist,” especially in its current, demeaned American form. As circulations dwindle and newspapers disappear, the political cartoonist has become an endangered species. In order to survive, these working stiffs have been reduced to making tepid gag cartoons about current events, avoiding any whiff of controversy, since one canceled subscription or lost advertiser can spell death for yet another paper.

Of course Art Young’s profession is not always and everywhere dismissed as trivial — just ask the murdered Charlie Hebdo artists. And it’s not all about Mohammed: tin-pot despots in India, Iran, Malaysia, Syria, and Venezuela, to name a few recent offenders, have acknowledged how potent cartoons can be by offering tribute to the cartoonists in the form of police harassment, huge fines, long prison terms, and torture.

In Young’s day — he was born the year after the Civil War ended and died while the Second World War was still raging — the power of the political cartoon to shape thought and mobilize opinion was a given. He grew up in a small town in Wisconsin, and his cracker-barrel manner was picked up around the cracker barrel in his father’s general store, where he also exhibited his first cartoons. Gustave Doré’s woodcut illustrations for Dante’s Inferno made a deep impression on him (he wrote and drew three versions of his own up-to-date Inferno over the years), as did Thomas Nast’s Boss Tweed cartoons for Harper’s Weekly. A high-school dropout, Young sold his first cartoon to Judge at seventeen and then moved to Chicago, where he studied art and began to draw for newspapers.

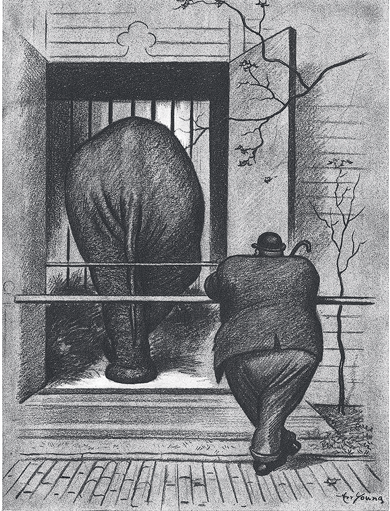

The In and the Out of Our Penal System, from Puck, October 20, 1909, courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

He came to look back with remorse at the antianarchist cartoons he drew after the Chicago Haymarket riot of 1886, as he slowly evolved from a tepid Republican at twenty (which roughly translates into mainstream Democrat in today’s parlance) into a flaming socialist by forty-five. He was an editor and leading contributor to The Masses, the fabled Greenwich Village radical magazine, where he worked alongside John Reed, Max Eastman, Jack London, John Sloan, and Stuart Davis. He even ran unsuccessfully for legislative office in New York several times, on the Socialist ticket. His career as a cartoonist unfolded in newspapers ranging from Hearst’s New York Journal to the Daily Worker and in magazines with sensibilities as different as The Saturday Evening Post and The New Yorker — as well as in his own short-lived, cheerily titled Good Morning, whose masthead declared, “To laugh that we may not weep.” When he died, at age seventy-seven, he was mourned by a spectrum of colleagues, friends, and admirers that included Carl Sandburg, Ernest Hemingway, Langston Hughes, Helen Keller, Charlie Chaplin, and even Walt Disney.

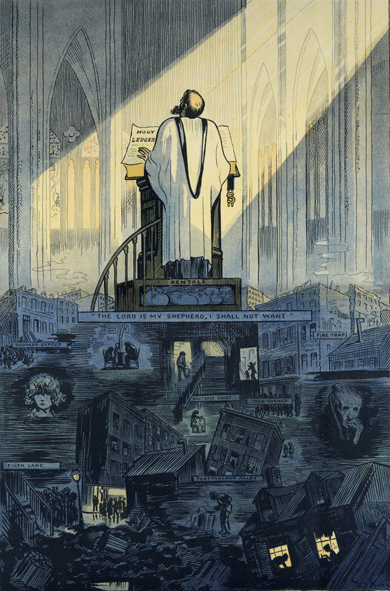

In 1909, a drawing Young made for Puck shamed New York’s Trinity Church, which had (and has) vast real-estate holdings, into tearing down and replacing the pestilent slum buildings it profited from. He happily accepted the term “propaganda” to describe his work, which he saw simply as propagating his own ideas. His contempt was reserved for the editorial prostitution involved in drawing for an editor’s convictions rather than one’s own. (Young confessed that he didn’t have convictions until he was about forty, when he put his mouth where his money wasn’t — refusing lucrative commissions from mainstream magazines and newspapers to take the vow of poverty that comes with working for the radical press.)

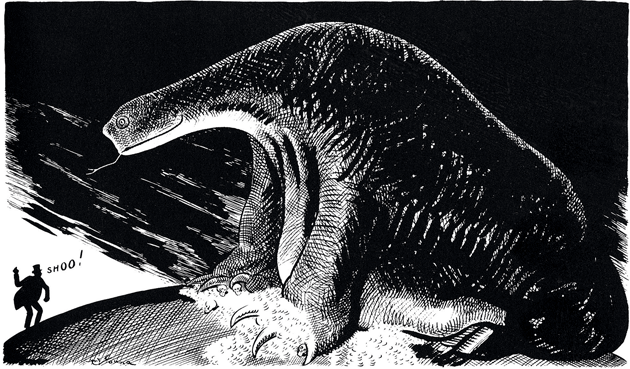

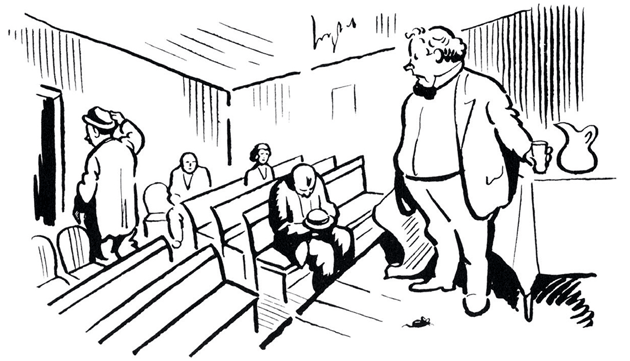

The Uprising of the Proletariat, from The Best of Art Young © 1936 The Vanguard Press, Inc., New York City

Holy Trinity, from Puck, January 6, 1909, courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

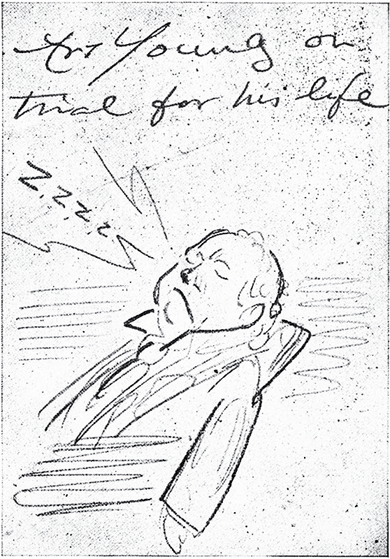

He was never quite convicted for his convictions, though the Associated Press did sue him for libel after he (accurately) accused it of covering up the bloody details of a West Virginia coal-miners’ strike. During the First World War, he was tried for treason for his pacifist cartoons in The Masses. He had to keep being nudged awake in the courtroom, and doodled an endearing portrait of himself snoring in his chair, captioned “Art Young on trial for his life.”

He was as good at making powerful enemies as George Grosz, who was variously tried for blasphemy, slander, and obscenity in Germany before fleeing to America when the Nazis rose to power, but Young didn’t have Grosz’s talent for hatred. His indignation was visceral, but his generous soul and empathic heart put him in the same Olympian league as Honoré Daumier. (Grosz and Daumier were painters as well as cartoonists, which helped keep them from slipping into the cultural memory hole that has swallowed Young.)

Political cartoons usually have a short half-life — comments on the passing parade are just confetti to be tossed out after the parade has gone by, salvaged mostly by historians or other political cartoonists looking to recycle them. Even Young’s boyhood hero, Thomas Nast — who gave us our contemporary image of Santa Claus and its antonym, the Republican elephant — is remembered mainly because his cartoons are useful for spicing up the gray monotony of American-history textbooks. Young’s work might be in some high-school textbook I haven’t seen, but that’s not what makes him important. Discussing his selection process for the work in his 1936 collection, The Best of Art Young (the only major retrospective of his work, at least until Fantagraphics Books releases The Art and Life of Art Young later this year), the artist wrote:

I did not spend many years of my life cartooning the trivial turns in current politics. Although a few of these are related to the topical issues of other days, it will be noted that practically all of them are generalizations on the one important issue of this era the world over: Plutocracy versus the principles of Socialism.

Young, like most progressives of his time, might have been a bit disheartened to find out that the grand Soviet experiment kinda, um, fizzled badly, but because he kept his eye on the fundamentals, his cartoons are rarely musty artifacts from yesterday’s papers but seem like urgent dispatches from tomorrow’s news. His classic 1911 Life cartoon, Capitalism (amusingly subtitled The Last Supper), depicts terminal gluttony. Whichever Republican ends up representing today’s one-percenters will have to slug it out with Hillary Clinton to see who wins the right to use this icon as their avatar in future World of Warcraft games.

I love that drawing, one of the artist’s clearest and most straightforwardly angry indictments, which damns the greedy beast to plummet directly into Art Young’s Inferno. But there is somehow an elusive touch of compassion even for this monster who heedlessly guzzles swill from his bejeweled cauldron. Young’s ability to hate the sin but not the sinner arises from his deeply ingrained sense of humor, which is manifested in masterful exaggeration — one can’t draw that creature’s body gesture without inhabiting the pose. The drawing is built on the artist’s recognition of his own — and everyman’s — capacity for gluttony, an understanding that we are all closer to animals than gods. It’s a theme he visits often in his work. (See, for example, Man and Beast, gloriously captioned with a quotation from Hamlet: “There’s a divinity that shapes our ends.”) The cartoonist’s lightness of being allowed the audience to bear the unbearable. It separates his work from the shrill, self-righteous sentimentality of many of his radical political-cartoon comrades. Even the prosecuting attorney in Young’s trial for treason was forced to agree with the defense attorney’s statement that “everybody likes Art Young!”

If Young hasn’t been sufficiently remembered, it is not because his pictures aren’t memorable. He’d studied to be a painter, but said he preferred a large audience to being displayed on a rich man’s walls. He was impatient with pictures that didn’t make a clear point. This need for content is personified by Trees at Night, his series of landscape drawings that was gathered in book form in 1927. Here he reclaims the landscape — usually a painter’s domain — as ground for a cartoonist’s imposed meanings by anthropomorphizing his silhouetted willows with painterly washes so they literally weep.

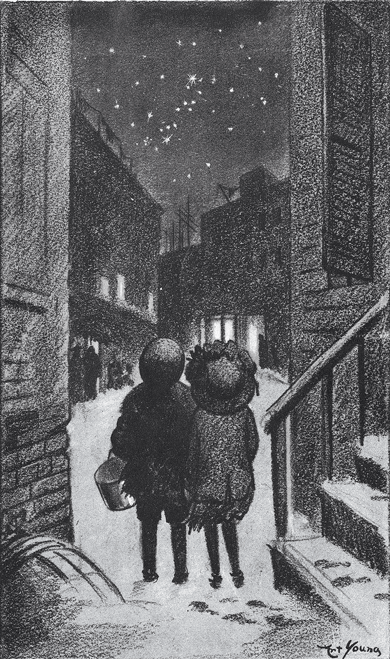

Chee, Annie, Look at de Stars—Thick as Bed-Bugs, from On My Way © 1928 Horace Liveright, New York City

Young told Max Eastman, his fellow conspirator at The Masses, that he was as devoted to the aesthetic elements of his work as any painter. “I worry over composition, drawing, light and shade, elimination — above all elimination — from breakfast time to dinner.” I’m pretty sure that he was referring not to his digestive tract but to the cartoonist’s craft of making a spare, efficient image. There’s a stylistic progression from his youthful drawings, which emulate Doré’s detailed wood engravings and Thomas Nast’s tight cross-hatchings, to his signature mature style of streamlined ink lines that echo early-twentieth-century woodcuts. The forceful graphic rigor of these later drawings is reminiscent of Rockwell Kent, his younger contemporary and comrade — but without Kent’s sometimes strained seriousness. Though Young is comfortable with various black-and-white media, including crayon drawing and painted washes, it’s his boldly composed later line work that fully embodies the paradox of humble virtuosity.

Young was searching for pictures that were coherent intellectually as well as formally. Saul Steinberg defined this difficult process as making an image that, once seen, can never be unseen — and Young was a world-class master at distilling his thoughts into unforgettable formulations. A cartoon’s power derives from its capacity to echo the ways our brains work. We think in small bursts of language and in stripped-down icons. (I once read that an infant can recognize a simple smiley face sooner than its mother’s smile.) Young’s images were understandable to all classes and embraced by a wide swath of the always-bickering left. Nowadays, satire and ridicule have effectively moved to late-night TV comedy, but it’s the cartoon’s ability to essentialize that we so sorely need now. The Occupy movement might’ve had longer legs if it only had a great T-shirt designed by Art Young.

But I would be doing Young a great disservice if I left you with the impression that he was “just” a political cartoonist. Many of his cartoons have no overt political agenda, except insofar as everything is political. They are most often intentionally and genuinely amusing (though, astonishingly, never cruel or condescending). His drawing of two slum urchins holding hands and staring at the night sky while one says, “Chee, Annie, look at de stars — thick as bed-bugs!” is a poignant example of what it means to laugh that we may not weep. While many of Young’s political cartoons were direct lessons on America’s rigged economic con game, all of his work was also a lesson in empathy. We have never needed more of both.