December 28, 2014, dawned auspiciously cold and clear in southwestern Utah. Two hunters, Doug Blackburn and Gray Hansen, had risen before the sun to drive into the high plateau country of the remote Tushar Mountains, where they planned to hunt cougar. A fresh layer of snow had fallen overnight, and animal tracks stood out as legibly as sentences on a page. The air was still, meaning that scents would be easily picked up by the five hounds that waited, impatient, in the back of their pickup.

The hunters drove slowly through a steep valley. Blackburn, a barber, was stationed behind the wheel, and Hansen, a sergeant major in the Utah National Guard, sat beside him. From the vehicle, they peered into the sagebrush. Suddenly, a flash of gray-brown fur interrupted their vigil.

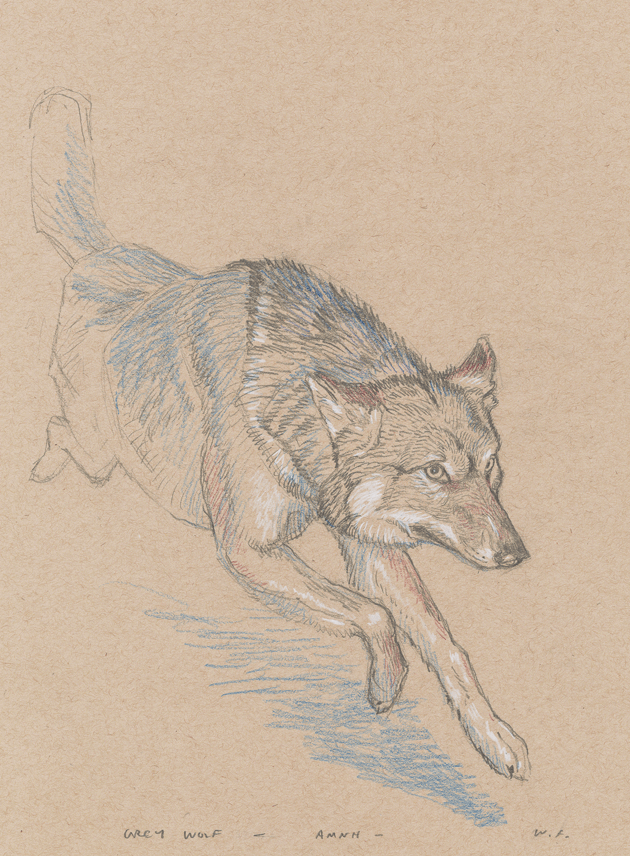

“Quick, shoot it!” Blackburn called out. Hansen, a trained marksman, took aim through a high-magnification scope attached to his .22-caliber rifle. He had a clear line of sight — an animal weighing close to ninety pounds was stalking through the low vegetation, about 175 yards away. He squeezed the trigger, and a sharp report rang through the valley. The mass of fur slumped to the ground. Hansen and Blackburn rushed up the hill, their footfalls muffled by the snow, and found the animal still breathing. Later, the two men would claim that they believed they had shot at a coyote. But in fact the creature at their feet was a gray wolf. One of the men — it’s not clear which — retrieved a pistol and shot the animal twice in the head. Only then did they notice its large paws and blocky snout; they also took note of the ungainly radio collar around its neck.

The wolf they had killed, a three-year-old female, was known to scientists as 914F and to the rest of the world as Echo, a name chosen by hundreds of schoolchildren in a contest. Earlier that year, she had become famous for completing an epic journey of more than 500 miles, setting out from the eastern fringes of Yellowstone National Park and, four months later, becoming the first documented wolf to arrive at the Grand Canyon in more than seventy years. After news of the shooting broke, there was widespread anger and sadness, but few considered the matter of 914F’s legal status.

In the area of Utah where 914F was shot, as in most of the United States, northern gray wolves are protected under the Endangered Species Act, which makes killing an endangered animal punishable by up to a year in prison and as much as $50,000 in fines. Hansen and Blackburn, however, were never charged. The Utah Division of Wildlife Resources quickly issued a press release declaring the shooting “accidental” — a ruling reaffirmed after a seven-month investigation led by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Not only did Hansen and Blackburn avoid imprisonment and fines, they escaped public scrutiny altogether. Until now, both men have remained anonymous.

Heavily redacted investigation documents I obtained from the Center for Biological Diversity revealed that Hansen and Blackburn had repeatedly told federal investigators that they thought they were shooting at a coyote. This was not merely a declaration of mistaken identity. The statement allowed them to evade prosecution using a loophole in the E.S.A. called the McKittrick Policy. The policy, which dates back to the final years of the Clinton Administration, and which some refer to as the Poacher Protection Act, has allowed people to kill endangered wildlife, claim ignorance, and escape without consequence.

In the hands of hunters, ranchers, and conservative politicians, the McKittrick Policy has been a potent weapon in a long-running campaign against wolves. But it has been especially insidious in Utah, where the state is trying to reduce the coyote population. “Someone can legally kill a protected wolf just by saying he thought it was a coyote,” Kirk Robinson, a conservationist based in Salt Lake City wrote to me in an email. “It’s basically a death warrant for wolves.”

In November 2015, in order to learn more about the circumstances surrounding 914F’s killing, I traveled to Beaver, a town of 3,000 people three hours south of Salt Lake City. Natalie Ertz, the executive director of an Idaho nonprofit called WildLands Defense, joined me. Ertz drove me to town in her dented Honda SUV, up a rugged, snow-covered road at the edge of Fishlake National Forest. After about an hour, she parked without a word and stepped out of the vehicle. Tall and lanky, with shoulder-length brown hair peeking out from beneath a stocking cap, she led me up a hill. Glancing at the GPS on my cell phone, she stopped and placed a bouquet of freshly picked sage on the snow. This was the kill site, where 914F was shot almost a year earlier.

Ertz’s connection to the animal was personal. An experienced wolf tracker, she was one of the last documented people to encounter 914F at the Grand Canyon the previous year. She described calling to the wolf at dusk from the ponderosa forests of the Kaibab Plateau: “She howled back. It was like speaking with nature itself.” Only weeks later, 914F lay dead on this remote mountainside.

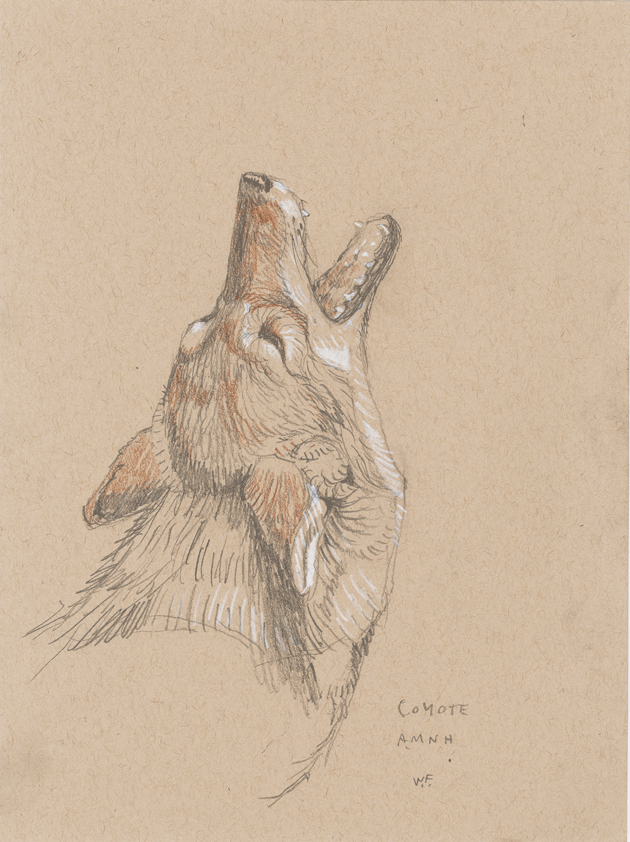

After we paid our respects, we headed to Beaver to attend its annual coyote-killing contest, in which cash prizes are awarded to the teams that kill the most animals in a single day. The contest is one of dozens of such events held across Utah, ostensibly because the animals pose a threat to elk, deer, and domestic livestock. An advertisement on Facebook for the previous year’s contest depicted the hunters’ adversary, under which a caption read there will be blood.

Ertz and I hoped to find Blackburn and Hansen, both of whom lived in Beaver, at the contest check-in, when the carcasses would be tallied and the winners announced. We parked in front of the Renegade Lounge, one of the few bars in town, and peered through binoculars into a dark alley. Around us, the signs of gun stores and bait-and-tackle shops glowed faintly in the falling snow. Soon, mud-spattered trucks began to pull in. One had a coyote tail affixed to the antenna, Davy Crockett–style. We took this as our signal to head in, following a thin trail of blood into the alley, where a dozen men wearing full camouflage stood before a wooden frame that was illuminated by halogen work lamps. Two game hooks dangled from the horizontal crosspiece; from each hung the carcass of a coyote.

The proceedings moved with grim efficiency. The teams brought their carcasses to a man wielding a large hunting knife. He punched a crude incision in each animal’s shin and passed the hook through, suspending one bloody carcass after another while a second man recorded the weights on a clipboard. By the end, more than a hundred dead coyotes — the majority of them pups and juveniles — were brought in by about fifty participating hunters. While a large adult coyote can reach forty-five pounds, few of those dangling in rigor mortis weighed more than fifteen or twenty. It was hard to see how creatures so small could be mistaken for a northern gray wolf, an animal easily four times their size.

Some consider Utah’s persecution of coyotes to be not only an ill-conceived and inhumane policy — they see it as an extralegal means of keeping wolves out of the state. “The Utah political establishment is united against wolves, almost to a person,” Robinson, the conservationist, who has worked in the field for two decades, said. Though the state hasn’t had a confirmed wolf pack in nearly a century, lawmakers have dedicated a substantial amount of energy and money to keeping them at bay. In 2010, they passed the Wolf Management Act, to “prevent the establishment of a viable pack in all areas of the state where the wolf is not listed as threatened or endangered.” The law requires state officials to call in the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to remove any wolves discovered in the roughly 81,500 square miles of land — 96 percent of the state — where they are protected under the Endangered Species Act.

In addition, state officials are fighting the F.W.S.’s efforts to expand the recovery zone of Mexican gray wolves up from New Mexico and Arizona to southern Utah and Colorado. The Utah Wildlife Board, an influential seven-member council that sets regulations for the state’s Division of Wildlife Resources, has accused the federal agency of populating its ranks with non-neutral, pro-wolf scientists. “Promoting or fostering Mexican wolf recovery in Utah and Colorado,” board chairman John Bair wrote to Gary Herbert, the governor of Utah, “is simply bad policy, bad science, bad for the Mexican wolf, and bad for the states strapped with the burden of hosting protected wolf populations.”

Utah’s anti-wolf campaign is led by two well-funded lobbying groups, Big Game Forever and Sportsmen for Fish and Wildlife, both headed by a wealthy hunting enthusiast named Don Peay. He has made it his mission to keep wolves out of the state. (Some call him the Don of Wildlife.) Peay’s ill will is indicative of the antifederal sentiment that has been spreading across the American West since the Sagebrush Rebellion of the Seventies and Eighties, with Utah at its center. The state is an incubator of ambitious legislation to erode federal authority, most notably the Transfer of Public Lands Act, which seeks the return to the state of 31 million acres of federal land (including Arches, Zion, and Canyonlands National Parks). And while President-elect Donald Trump has been vague about his stance on public lands, his election is sure to embolden supporters of the lands-transfer movement. In this politically charged climate, shooting a wolf is not simply machismo — it is a decisively antifederal act.

Wolves once roamed the expanses of pre-Columbian North America, from the boreal forests of Canada to the deserts of Mexico, in numbers that may have exceeded a million. But as soon as Europeans arrived, wolf numbers began to decline. The first official wolf bounty in North America was enacted in 1630; the Massachusetts Bay colonists were paid one shilling for each carcass. A decade later, the bounty had increased to forty shillings (equivalent to a month’s wages for the average Plymouth laborer). By the middle of the twentieth century, the federal government was paying hunters and trappers up to fifty dollars for each wolf they killed.1 This institutionalized extermination happened at the behest of the livestock industry, which for more than a hundred years has grazed animals in the public lands of the West, vociferously claiming that wolves pose a mortal threat to its livelihood.

As pressures on the rural American landscape multiplied, so did the methods of killing wolves. Over the past century, wolves have been shot from planes, strangled in snares, clubbed in their dens, and poisoned with strychnine, arsenic, and cyanide. The writer Barry Lopez points out in his book Of Wolves and Men that something in this effort has gone beyond the pragmatic concerns of “predator control.” This long-standing war against wolves, Lopez writes, is evidence of a deeper sort of malice:

Historically, the most visible motive, and the one that best explains the excess of killing, is a type of fear: theriophobia. Fear of the beast. Fear of the beast as an irrational, violent, insatiable creature. Fear of the projected beast in oneself. . . . At the heart of theriophobia is the fear of one’s own nature. In its headiest manifestations theriophobia is projected onto a single animal, the animal becomes a scapegoat, and it is annihilated. That is what happened to the wolf in America.

For four centuries, like a tide ebbing across the continent, wolves lost ground. By the 1960s, the northern gray wolf — North America’s preeminent symbol of wilderness — had been nearly wiped out in the contiguous United States. Only a few hundred animals survived, in remote, forested pockets of northern Minnesota and Michigan.

At around the same time, an ecological mind-shift began to occur, with pioneering research recognizing that wolves and other predators at the top of the food chain played an important role in keeping the population of herbivores such as elk and deer in check. Federal biologists began to discuss wolf restoration as a critical part of the effort to reestablish self-managing ecosystems. (In the words of environmentalist Aldo Leopold, ecologists were finally beginning to “think like a mountain.”) After the passage of the Endangered Species Act, in 1973, the F.W.S. established a recovery team, and in 1995 it reintroduced wolf populations to Yellowstone and remote sections of Idaho. The original release of sixty-six wolves has contributed to a population of about 1,700 today.

In January 2014, before 914F was spotted at the Grand Canyon, she had been trapped by biologists from the Wyoming Game and Fish Department near Cody, Wyoming, fitted with a radio collar (the one that Hansen and Blackburn discovered on her body), and released back into the wild. Coordinates show that 914F skirted the eastern boundary of Yellowstone for the first half of the year. She headed south, most likely in search of a mate, probably traversing a network of peaks, mesas, and canyons running through western Wyoming and central Utah, a vast wildlife corridor that connects Yellowstone to the Grand Canyon.

To get a better sense of where 914F might have entered Utah en route to Arizona, I joined Adam Brewerton, a biologist with the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources. He took me out to the Bear River Mountains for a tour. Brewerton oversees “sensitive” species in this part of the state, among them northern gray wolves. And yet Brewerton said that wolves took up little of his daily routine. Other than lone dispersers like 914F, wolves are rarely seen; according to the D.W.R., since 2002 there have only been around a dozen confirmed wolf sightings in Utah.

This region of high plateaus, deep ravines, and gently sloping ridges covered in limber pine, aspen, and Douglas fir would be ideal habitat for wolves. Politically, however, it is dangerous terrain. We were in the heart of the “delisted” zone — a roughly 3,500-square-mile triangular swath of the state’s northeastern corner where wolves may be killed without penalty if they are deemed to pose a threat to people, pets, or livestock. The decision to strip northern gray wolves of their endangered status in this part of Utah came about in 2011, as a last-minute rider to a budget bill that was necessary to avoid a government shutdown — the first time an endangered species lost protection not on the basis of scientific recommendations but through an act of Congress.

As snowflakes began to accumulate on the windshield, Brewerton decided that it was time to head out of the high country. He crept down a ridge toward the highway. Bear Lake appeared as an aquamarine blot far below us. Within a half hour, we were nearly off the plateau, but found our path blocked by a gate — the last 200 yards of the road crossed a private ranch. Risking the ire of the landowner, I opened the gate and Brewerton drove through. As we rounded a bend, a woman in jeans and a beige shirt stepped out of her house, glaring at the truck’s D.W.R. logo. Brewerton stopped the car and rolled down his window. He pointed to his GPS and said meekly that he had thought the road was public.

The woman was unmoved. Her name was Cindy Wamsley, she explained, and her family had grazed cattle in this part of northern Utah since the 1860s. “What’s the D.W.R. doing up here anyway?” she asked, with clear hostility in her voice.

Brewerton said that he was assisting me in reporting on wolves in the region.

“Wolves, huh?” She gave a wry smile. “Did you tell him about the one they just trapped over by Randolph? Did you tell him about the pack over by Swan Peak?” She went on to say that her brother-in-law had recently seen wolf tracks.

“We’re still checking into that,” Brewerton told her. (“It’s not confirmed,” he whispered to me.) Wamsley looked at me intently. She was clearly not buying the official line. Wolves, she said, had been a looming presence for generations. Now this menacing shadow of resurgent nature had reappeared. “Write this down,” she told me. “The wolves are coming. The D.W.R. says no, no, they might be coming. I’m here to tell you they’re coming. They’re coming and we’re not happy about it.”

The following day, I visited the nondescript three-story building on the outskirts of Salt Lake City that houses the headquarters of the Utah D.W.R. Amid drab cubicles and cramped offices was a menagerie of taxidermied animals and mounted heads: black bears, bison, badgers, ptarmigan, otters, grouse, elk, bighorn sheep. It was as if a wing of the American Museum of Natural History had been teleported under the fluorescent lights.

I sat down with Kim Hersey, who, as head of the state’s Mammal Conservation Program, oversees management of wolves that wander into the delisted zone. Hersey confirmed that a “wolflike” animal fitting Cindy Wamsley’s description had been trapped earlier in the week. Since 2002, she told me, there had been only three documented cases in Utah of a wolf killing livestock. Nevertheless, she seemed sympathetic toward ranchers. “If that’s your livelihood and you see one of your animals torn apart,” she said, “that is going to viscerally affect you.”

Emotions aside, there is little evidence to suggest that wolves pose a serious threat to the nation’s livestock. Of 3.9 million cattle deaths reported in 2010, only 220,000, or 6 percent, were attributable to predators. (Inclement weather caused twice as many deaths.) And of these 220,000, wolves accounted for a mere 4 percent. Domestic dogs killed more than twice as many cattle as wolves did.

Hersey claimed that Utah wildlife managers are not opposed to the presence of wolves. But, she said, the animals should be managed on terms determined by Utah, not the federal government. “We want state control of these animals and we advocate for them to be managed as other predators in Utah are,” she told me.

When I asked if by “other predators” Hersey meant coyotes, she pointed me down the hall to the office of Leslie McFarlane, who was then the head of Utah’s coyote-bounty program. McFarlane explained that because coyotes are considered nuisance animals, the state does not conduct population surveys or establish quotas as it does for animals such as mountain lions and black bears. Thus, the number of coyotes that may legally be trapped, poisoned, or shot in the course of a season is virtually unlimited.2 In 2015, Utah paid out more than $400,000 for more than 8,000 coyotes killed.

McFarlane said the bounty has been in place since 2012, as part of the Mule Deer Protection Act. The goal is to target coyotes in places where mule deer give birth — yet the bounty allows animals to be killed wherever they are spotted. Moreover, because the D.W.R. does not track coyote populations, McFarlane could not say whether the bounty program had effectively reduced the number of coyotes — nor whether it had contributed to rising mule-deer numbers.

Some say that bounty programs may actually have the effect of increasing coyote populations. Like wolves, coyotes are considered “behaviorally sterile,” meaning that only alpha males and females in a population typically breed. When an alpha is killed, that role is likely to be filled by a juvenile. Additionally, a drop in wolf populations can contribute to a rise in coyote populations. William Ripple, an ecology professor at Oregon State University, explained to me that when wolf populations are robust, the wolves compete with coyotes for prey (and in some cases eat the coyotes), reducing coyotes’ breeding rates. The numbers bear this out: in places where wolves have rebounded, such as Michigan’s Isle Royale Park and Yellowstone, coyote populations dramatically declined or were eliminated entirely. “If you want to deal with an overpopulation of coyotes,” said Ripple, “wolves are not a bad place to start.”

Currently, the greatest threat to the survival of wolves may be the McKittrick Policy, the loophole in the E.S.A. The policy was named for Chad McKittrick, a Montana hunter who was convicted of killing a Canadian gray wolf in 1995. He told wildlife officials that he thought he was shooting a “wild dog” — even though a friend who was with him at the time testified that McKittrick identified the animal as a wolf before he pulled the trigger. (He was later found to be in possession of the wolf’s pelt and head.) McKittrick was handed a six-month sentence, but his lawyers appealed, arguing that a conviction for an “illegal take” under the E.S.A. required that the defendant know the animal is an endangered or threatened species before killing it. Their defense homed in on a single phrase of the law: “knowingly violates any provisions of the Act.”

Most scholars had seen this as a strength of the law, because it reduced the burden of proof that federal prosecutors needed to convict. A hunter could be prosecuted whether or not he thought he was shooting at an unprotected species, Daniel Rohlf, a wildlife-law professor at Lewis and Clark Law School, told me. “In other words, you’d better be darn sure before you pull the trigger.”

McKittrick’s lawyers argued otherwise. The word “knowingly,” they asserted, meant that the government was required to prove McKittrick was aware he was shooting an endangered wolf rather than simply “an animal.” The Ninth Circuit Court rejected that argument, and as a last-ditch effort, McKittrick’s attorneys filed a petition to the Supreme Court. Their petition was denied. Case closed — or so it seemed.

In February 1999, Seth Waxman, the U.S. solicitor general, gave an order that seemed to contradict the rulings of the courts. A DOJ policy memo put his decree into action: “All Department prosecutors are instructed not to request, and to object to, the use of the knowledge instruction at issue in McKittrick.”

Thus the McKittrick Policy was born. For nearly two decades, it has hamstrung efforts to protect threatened and endangered wildlife. “There are people poaching and we can’t prove it,” said Marie Palladini, a criminal-justice professor at California State University, Dominguez Hills, who worked as an F.W.S. agent in southern California when the policy was issued. In addition to wolves, Palladini told me, grizzly bears have been “mistaken” for black bears, whooping cranes for sandhill cranes, California condors for turkey vultures.

While it’s not clear why the DOJ chose an interpretation of the law that departed from previous court decisions (an agency spokesperson offered only a rehash of the policy itself, and Waxman sent me an email saying he had “no recollection of the circumstances”), the McKittrick Policy’s legal and ideological origins can be traced to the late Antonin Scalia, the conservative Supreme Court justice and avid hunter. In Babbitt v. Sweet Home Chapter of Communities for a Greater Oregon, a 1995 case that debated whether the E.S.A.’s protections included harm to animals from habitat destruction, Scalia wrote a dissent that lays out, almost word for word, a framework for the McKittrick Policy. “It is quite possible to take protected wildlife purposefully without doing so knowingly,” he wrote.

The hunter who shoots an elk in the mistaken belief that it is a mule deer has not knowingly violated [the law] — not because he does not know that elk are legally protected but because he does not know what sort of animal he is shooting.

Ed Newcomer, an F.W.S. special agent, says that many federal wildlife agents do not even understand the origins of the policy that has severely hindered their ability to enforce the E.S.A.: “They have been led to believe that a court made this decision, when in fact the highest court made a ruling that is exactly the opposite of how the policy is being applied by the Department of Justice.” It wouldn’t take much to negate McKittrick, he said — just a stroke of the pen by the attorney general. “It’s not a law. It could be rescinded overnight.”

At the coyote-killing contest in Beaver, the body count mounted, and Natalie Ertz and I kept a lookout for Blackburn and Hansen. They didn’t turn up — nor did we encounter any state or federal wildlife officials, whose presence I might have expected. As the count was nearing an end, a man wearing a soiled camouflage-print cap asked the organizer, Brennen Orton, how he could get rid of the coyote carcasses after the night was over. “You can have them,” he offered.

“I don’t want ’em,” Orton replied. He said the man could submit the bodies for payment if he was registered under the coyote-bounty program. The man said he was not. Besides, he added, even if he had been, he wouldn’t want to go through all the work of cutting jawbones and scalps from the animals — a grisly and laborious process — for a mere fifty dollars each. Orton proposed the next best course of action. “Just take them out into the sagebrush and dump them,” he said. “Make sure you’re a few miles out and you’ll be fine.”

A week later, from my home in the Bay Area, I called Doug Blackburn. His voice came across the line in a heavy Western drawl. I asked if he was involved in the killing of a female wolf near Beaver, Utah, in 2014.

“Yep.”

“Were you the one who shot the wolf?” I asked.

“No,” Blackburn replied. “But I was right there. I would have done it, but he beat me,” he said, meaning Gray Hansen. “I was driving.” He told me he couldn’t say anything else and that his lawyer would be in touch.

Calls to Hansen for comment went unanswered, but a few days later, Blackburn called back.3 This time he struck a far more penitent tone, but continued to maintain his innocence — which is to say, his ignorance. He told me that he and Hansen didn’t realize what they’d done until they picked up the animal. “Hell, I still thought it was a coyote,” he said. “Gray grabbed the back end and I grabbed it by the head, that’s when I felt something.” It was the radio collar. Unsure of what to do, the two weighed their options. “I said, ‘We better go to the fish cop’s house and tell him it’s got a collar on it.’ ” So they drove forty-five minutes to the home of a Utah D.W.R. officer (though wolves in that area fall under federal jurisdiction).

“I was born and raised in these mountains,” Blackburn said, recalling 914F. “That’s the last thing you think you’re going to see — a wolf. I still can’t believe it was here.”

Blackburn seemed to want to convince me of his sincerity. But it shouldn’t matter whether the two hunters thought they saw a wolf or a coyote. Before the McKittrick Policy, enforcement of the Endangered Species Act was guided by a much older piece of hunting wisdom: “Know what you are shooting at before you pull the trigger.” (A version of this is printed in every hunter’s safety manual.) That wisdom is critical today, as the number of animals on the United States’ threatened and endangered list has grown to more than 700 species. It means taking personal responsibility for animals you kill; not knowing what you are shooting at is not only an affront to the core ethics of hunting, it was once punishable as a crime.

But what of the sanctioned killing of coyotes in Utah and other states, an indiscriminate exercise that closely resembles the policies of mass extermination that resulted in the near extinction of wolves in the previous century? I thought back to the final minutes of the contest in Beaver. The snow was falling heavily by then. More trucks arrived, and soon the alley was a blur of camouflage, fur, and blood. Many animals had gaping wounds through which their entrails spilled out onto the snow. The hunters handled the carcasses like bags of refuse, swinging the bodies from the trucks by their legs.

A child no older than eight or nine, scrawny inside his insulated Denver Broncos jacket, ran through the crowd, playfully kicking the stiffening carcasses. His antics were received with smiles, chuckles, high fives. Emboldened, he hopped up on a bloated, dead coyote, as if squashing a water balloon.

I approached the imposing man who had accompanied the boy. He told me he was the boy’s uncle. I asked how many coyotes they’d managed to shoot. “Only one,” he said. “We were just out for fun.” I asked if his nephew had participated. He nodded but said that the boy never pulled the trigger — contest rules stipulated that participants be at least eighteen years old.

With dozens of bodies laid out on the ground, the air became infused with the odors of blood and excrement. The boy ran to his uncle’s side, waving his hand in front of his face. “It stinks!” he shouted.

“Yep, those are some dirty dogs,” the man replied.

I asked him whether this year’s contest had yielded more animals than last year’s. He wasn’t sure, but said he expected that was the case. “I hope we kill them all.”