Let us think the unthinkable. Let us imagine Donald Trump’s potential path to reelection as president of the United States.

He is deeply unpopular, the biggest buffoon any of us has ever seen in the White House. He manages to disgrace the office nearly every single day. He insults our intelligence with his blustering rhetoric. He endorses racial stereotypes and makes common cause with bigots. He has succeeded in offending countless foreign governments. He has no idea what a president is supposed to be or do and (perhaps luckily) he has no clue how to govern. Of the handful of things he has actually managed to achieve, nearly all are toxic.

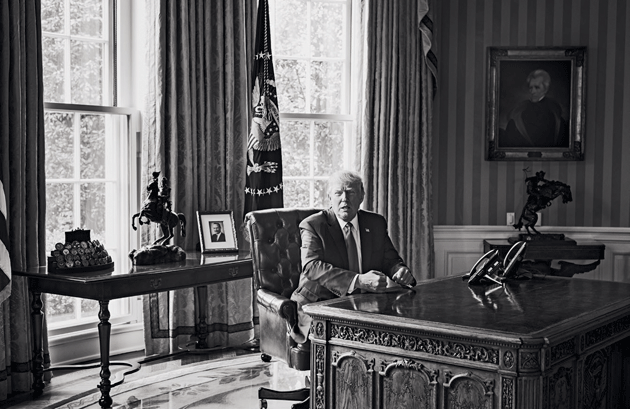

Donald Trump in the Oval Office, 2017 © Christopher Anderson/Magnum Photos

Now: imagine his disastrous rule reaffirmed by an enthusiastic public, giving him four more years to insult and offend and enact even more poisonous measures. Reader, it could happen. We know it could happen because it has happened before. Widely despised presidents get themselves reelected all the time. Men who are regarded as incompetent, callow, senile, or racist sail back into office, and are even canonized as heroic figures once they retreat into the postpresidential sunset, clearing brush or painting oil portraits.

There are many paths to such rehabilitation for Trump. Imagine him, Reagan-like, lifted up on a wave of public adulation. The economy is firing on all cylinders; the ships of many nations are parading through New York Harbor; the fireworks are going off overhead and Trump is announcing that America is back, standing tall.

Or imagine him, Dubya-like, vowing vengeance after a terrorist attack on American soil. He picks a fight with some annoying but unrelated nation, the news media rallies around him (he has finally achieved maturity as chief executive, they say), and once victory is certain, Trump lands a jet on the deck of an aircraft carrier in a cleverly tailored flight suit: mission accomplished.

I admit that at the moment it is difficult to conceive how Donald Trump might turn that corner. Every day the circling investigators come a little closer. Every day he tweets something stupid. Every day there is a disclosure — an alleged affair with a porn star, another emoluments snafu — of the kind that would have sunk previous administrations. Besides, the presidents I mentioned above were capable politicians, advised by men and women of a certain practical cunning. Reagan and Bush both had some basic grasp of what voters traditionally wanted from their politicians and how to go about delivering it. Trump has no such understanding. His election in 2016 was little more than an obscene gesture by an angry public using the candidate as its instrument. While the populace seems to be losing patience with such symbolism — at least to judge from Trump’s lousy approval ratings — the man himself shows little inclination to transcend the role that got him elected. How could the nation possibly return him to Washington for a second term?

Here is the exercise: let us imagine Donald Trump’s path to reelection. We take for granted (perhaps incorrectly) that he wants to be reelected, that the job amuses or excites him enough that he desires to stay in the White House. We further assume that he is not impeached, that he does not maneuver the country into a disastrous war, that he does not stage (or fall victim to) a military coup, and that he goes about campaigning for reelection by all the standard methods available to an American politician. And that he wins. Again.

For the best idea of how such a scenario might unfold, we need only look back to the late Nineties, when things were good and America was happy with its rascally chief executive, Bill Clinton. Throughout the second term of his presidency, Clinton’s approval ratings hovered near the 60 percent mark, occasionally spiking up toward 70 percent. These nosebleed numbers, remember, occurred after the president was caught in his dalliance with the White House intern Monica Lewinsky and as the House of Representatives was actually in the process of impeaching him. The irony of it all was lost on no one: self-righteous politicians hated Bill Clinton, but the American public loved the jolly horndog in the Oval Office.

Clinton’s extraordinary popularity, however, was not merely a reaction against the pharisees in Congress. Nor had the individual components of Clintonism (NAFTA, say, or telecom deregulation) fired the imagination of the masses. No. People loved Bill Clinton first and foremost because the economy was doing so well. He had taken over the government on the heels of an ugly recession, and now look: Gasoline was cheap and the stock markets were on a tear. The Dow Jones Industrial Average, which had been a little north of 3,200 when Clinton took office, passed 10,000 in March 1999. The Nasdaq — the miracle index of the decade — ascended even more dizzyingly.

Clinton’s extraordinary popularity, however, was not merely a reaction against the pharisees in Congress. Nor had the individual components of Clintonism (NAFTA, say, or telecom deregulation) fired the imagination of the masses. No. People loved Bill Clinton first and foremost because the economy was doing so well. He had taken over the government on the heels of an ugly recession, and now look: Gasoline was cheap and the stock markets were on a tear. The Dow Jones Industrial Average, which had been a little north of 3,200 when Clinton took office, passed 10,000 in March 1999. The Nasdaq — the miracle index of the decade — ascended even more dizzyingly.

Declining to mess with a good thing, the Federal Reserve kept interest rates relatively low, stoking the euphoric culture of the New Economy, and the country went crazy. Thanks to a novelty called the internet, it was said, humankind had entered an entirely new era. Information was now perfect, the business cycle was suspended, the boom would go on forever, and the world’s weak and marginalized would embrace free trade and be lifted up by the loving kindness of the market. Or whatever. The ecstatic style of the moment was so widespread that even a sober and responsible economist like Kevin Hassett — now the chair of Trump’s Council of Economic Advisers — coauthored a hyperventilating book called Dow 36,000.

It was all, of course, a bubble — not to mention a fraud and a con. It would all come apart shortly after the turn of the century in a dazzling series of corporate scandals and market crashes. And even while the bubble lasted, its benefits were lavished mainly on the wealthy. Still, there was something else about the late-Nineties boom, something real, something that accounted for Clinton’s popularity: wages for ordinary workers actually rose during those years. Unemployment was so low for so long during the Clinton era that employers briefly found themselves competing for workers rather than dismissing their entreaties. Indeed, the late Nineties were the only sustained period since the early Seventies when wages for ordinary workers went up in real terms. Hence the flavor of universal prosperity that still seems to envelop the Clinton boom in the public mind.

No, the boom didn’t last. And no, it wasn’t really Clinton’s doing. Joseph Stiglitz, the chairman of Clinton’s Council of Economic Advisers, has described the policy decisions that preceded the roaring economy of the late Nineties as a series of “lucky mistakes.” Clinton’s team, in Stiglitz’s telling, made wrong move after wrong move — chasing a balanced budget, deregulating banks — but by chance, things worked out for them. The day after he was elected in 1992, Clinton said he would “focus like a laser beam on this economy,” and lo and behold, he seemed to deliver. The cult of Clinton was born.

That is the prelude to today.

When members of the punditburo assess Donald Trump’s record as chief executive, they generally turn to his small-minded remarks, his many falsehoods, his noisy enthusiasm for white supremacists and foreign dictators. They are aware that the economy is accelerating under his watch, but that doesn’t really figure into their calculations — that item they file in a separate bin. After all, as everyone knows, Trump cannot rightfully claim credit for the long, slow march back to prosperity after the 2008 recession. He took over only a little more than a year ago, and besides, you don’t get unemployment down by picking fights with NFL players or inveighing against a phantasmal immigrant crime wave.

That Trump has no right to the glory of the current boom doesn’t stop him from grabbing it, however. Declaring that the robust economy had made him “unbeatable” for reelection, Trump mused in December that his slogan for 2020 might be, “How is your 401(k) doing?” As I write this, unemployment is at its lowest level since 2000, and one of its lowest levels ever. People who left the workforce in despair during the recent recession appear to be rejoining it. Consumer confidence is high. The economy is running at what the Wall Street Journal calls its “full potential,” meaning that actual output is slightly higher than theoretical estimates of maximum possible output. Share prices are high, too, even after a jolting market correction in early February.

But stock ownership — even when it’s done via Trump’s vaunted 401(k)?s — is hardly the optimal vehicle for putting money into the hands of ordinary people. That would be improved wages, which we saw briefly in the late Nineties and frequently in the years before 1973. These days, however, flat or sinking wages are a standard feature of Western economies: with unions weak and an arsenal of wage-suppression techniques in the hands of management, business booms have for many years been confined to shareholders only.

Photographs © Ben Sklar

Here’s where our story takes a curious turn. Trump, for all his ignorance, seems to be aware of this. Wage stagnation, a grievance usually associated with leftish economists and AFL-CIO types, was one of the big talking points for both candidates during the 2016 campaign. It was also the focus of one of Trump’s great boasts. Under his presidency, he pledged, “Prosperity will rise, poverty will recede, and wages will finally begin to grow, and they will grow rapidly.” As with most Trumpian utterances, this was probably just so much bullshit. Empty syllables, vigorously pronounced, signifying nothing. After all, the people who would pay those higher wages would be Trump’s billionaire pals, the same people he’s appointed to his Cabinet and showered with tax cuts. Higher wages would mean companies forgoing big CEO paydays and special dividends for shareholders and all that tycoon-pleasing stuff. And the obvious and direct things that government can do to help working people — raise the minimum wage or make it easier for workers to join unions — are off the table with Republicans in charge of Congress.

Trump might get his wage growth anyway. Right now the labor market is so tight that Walmart, a company famous for taking a hard line on employee pay, felt it had to increase its starting wage from $9 an hour to $11. (Republicans immediately took credit for this development, of course.) A story in the New York Times in January pointed out that employers in Wisconsin were so desperate to find workers that they were hiring convicted criminals while they were still in prison. Data showing an uptick in wages was sufficiently convincing to cause a sharp correction in stock prices in February.

What these news items suggest is that given where we are now, it won’t take much to make this economy work for ordinary people. Or appear to work, anyway. Even a small stimulus would do it. Donald Trump quite likely understands this, along with the connection between wage growth and Bill Clinton’s route to presidential popularity. Even with a loutish Republican Congress, there are plenty of things he might do to make this economy into a good one for ordinary working people — meaning just good enough, for just long enough, to get himself reelected. I suspect that we will soon see proposals of exactly this kind.

The obvious stimulus Trump might propose is his famous trillion-dollar infrastructure plan, of which he made so much on the campaign trail and which he dusted off for his State of the Union speech in January. Let’s assume that the version of the infrastructure plan he proposes is the one that dumps about 80 percent of the financing onto state and local governments and the private sector. This is far from the best way to rebuild a country’s infrastructure, of course, but it would certainly have a positive (if temporary) effect on wages somewhere down the line. Should such a plan be implemented, according to the infrastructure expert Michael Likosky, “We’re going to see a labor shortage, and we’re going to have a higher rate of productivity.” Which guarantees one other thing: “Wages will go up.”

Smaller stimulus efforts might also do the trick. In Nixonland, a celebrated history of the Vietnam era, Rick Perlstein recalls how the Nixon Administration tried to improve the economy for the 1972 political season by boosting federal spending in large but noncontroversial ways. (There was, for example, the “two-year supply of toilet paper bought in one shot by the Defense Department.”)

We might also see smaller, localized infrastructure programs with relatively picayune price tags but outsized political potential. Take the various plans that are currently under way to fix the poisoned water supply of Flint, a city in the critical swing state of Michigan that for decades has been synonymous with the suffering of both the black and the white working class — hugely important voting blocs. Just imagine the effect, as one leading Democratic politician conjectured to me, were the Trump Administration to increase those efforts in a massive way, causing an army of well-paid pipe fitters to descend on central Michigan.

The president’s team could easily dream up similar mini–New Deal schemes for other deindustrialized locales in the Midwestern states that are now the key to the presidency. Not only would such proposals attract Democratic votes in Congress (hey, bipartisanship!), they would also do much to counter Trump’s racist reputation — a key consideration for someone who intends to win elections in a country that grows less white every year.

Then there is free trade. Back in 2016, when Candidate Trump visited Flint, he made a caustic remark about the city’s misfortunes: “It used to be that cars were made in Flint and you couldn’t drink the water in Mexico. And now the cars are made in Mexico and you can’t drink the water in Flint.” Trump blamed this reversal on NAFTA, the original neoliberal economic deal and one of his favorite rhetorical targets on the campaign trail.

Trump seemed vaguely to understand that trade agreements were connected to wage stagnation. (“My trade reforms will raise wages, grow jobs, add trillions in new wealth into our country,” he said in a speech in Ohio in 2016.) He may or may not have understood that whatever the details of such agreements, they often furnish employers with a weapon they can wave at working-class communities: the threat of shipping jobs overseas. Indeed, as the economy has heated up, American companies have been sending jobs offshore at an ever more rapid pace.

A Trump campaign rally in Lowell, Massachusetts, January 4, 2016 © Mark Peterson/Redux

What if Trump were to actively discourage that tactic, or strike some largely symbolic blow against it, or merely bad-mouth it? As it happens, NAFTA is being renegotiated, and we may well see Trump use those negotiations to do one or more of these things. The president, always a fan of burning down the village in order to save it, is currently threatening to scuttle the whole agreement: “A lot of people don’t realize how good it would be to terminate NAFTA, because the way you’re going to make the best deal is to terminate NAFTA.” But even if NAFTA is mostly reaffirmed in the end, Trump could use the negotiations to dissuade employers from offshoring jobs — or he could single out some random company and hit it with substantial fines for doing so. That, too, could change the wage equation. Again: it wouldn’t take much, given a business climate like the present, to have some effect.

Of course, all of this assumes that Trump’s rhetoric in 2016 was sincere: that he really means to be the country’s “blue-collar billionaire” and to stop what he called, in his famous (if awkward) simile, an “American carnage” of “rusted-out factories scattered like tombstones across the landscape of our nation.” It also assumes that Trump knows that the interests of billionaires and those of working people are not actually in alignment with each other.1

Neither is a reasonable assumption, really. One of the deepest faiths of modern conservatism is that workers and management share some mystical bond — that what workers want more than anything is an ass-kicking billionaire as their boss, a guy who isn’t afraid to growl, “You’re fired.” As I write this, Republicans are still celebrating the enactment of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, a colossal windfall for shareholders and corporate management that Trump pushed for on the risible grounds that it would be a windfall for workers. Senator Chuck Grassley, Republican of Iowa, actually saw fit to rationalize one provision of that law with the following bouquet to Middle America: “I think not having the estate tax recognizes the people that are investing, as opposed to those that are just spending every darn penny they have, whether it’s on booze or women or movies.”

Even so, Trump might do nothing at all and still get the wage growth he needs for a second term. His luck could turn out to be even better than Clinton’s. After all, the forces that are causing the economy to run in high gear were set in motion years ago by Barack Obama and Janet Yellen, the former chair of the Federal Reserve. Should matters continue along this course for very much longer, Trump might be able to deliver on his promises. As I was told by Josh Bivens, an economist with the left-leaning Economic Policy Institute, “If we stick at this level of unemployment for a couple of years, you will start to see some decent wage growth.”

Of course, the Fed could decide somewhere down the line that wage growth implies inflation and that interest rates must be raised — which is, incidentally, the desired course of traditional conservatives. But in the short term, that seems unlikely. Yellen, like her predecessors Alan Greenspan and Ben Bernanke, preferred to let the economic locomotive gather speed, and when Trump nominated Jerome Powell to succeed her in November, he pointedly chose a pro-growth Yellenite instead of a conventional inflation hawk.

Some of the potential Trumpery I have just described might have real effects. Other measures would deliver a fleeting sugar high. Still others would have no impact at all, aside from appearances. But any single one of them might just be sufficient to produce the deadly phenomenon we know as Trump’s reelection, while knitting together the new, faux-proletarian Republican Party that Steve Bannon used to fantasize about, the one he dreamed would “govern for a hundred years.”

Before you close this magazine, chuckle cynically, and take a sip of gin, think for a second about the cultural and political delusions a roaring economy and rising wages would surely generate — just as the tech mania of the late Nineties did, and just as the bull market of the Eighties did. Perhaps Donald Trump, elevated to the presidency in 2016 as an act of protest by what he called the “forgotten men and women of our country,” will actually appear to come through for them. Like Bill Clinton with his laserlike economic focus, Trump will seem to have delivered on what he promised: an economy that finally looks good for his supporters. For once, they will conclude, politics worked.

Cue the victory flotilla in New York Harbor. Cue the hundred-year night.

Now let’s examine a different scenario. It’s 1974, and inflation is out of control. Gasoline is so expensive that the economy is being injured. The president, who lives to inflame society’s divisions, is obviously a crook, and the denials mouthed by his dwindling band of defenders convince nobody. And so a new generation of Democrats is elected to Congress in enormous numbers.

To bring this scenario up to date, let’s imagine that Robert Mueller or some other investigator is quickly closing in on Trump with heaps of undeniable evidence. The Dow has stopped ascending, and wages have gone nowhere. More factories have rusted out. More newspapers are dead. More small towns have deteriorated, and opioids and meth are cutting even greater swaths across the hinterland. The president has achieved nothing except deregulation for polluters, angry alienation for every ethnic group in the United States, and tax cuts for the rich. No one believes a word Trump says, and the American carnage mounts in great heaps of ruined lives.

In such a scenario, every bit as likely as the ones mentioned above, it seems like a cinch: Democrats will easily sweep this preposterous man and his dysfunctional, divisive party into the gutter. Besides, what will Trump promise us in 2020, when nothing has improved for ordinary people? That he still means to “drain the swamp,” after essentially bathing in it for the previous four years? That he’ll need just one more term to revive the faltering coal industry? That he’ll Make America Even Greater Again?

Given such a setup, it might seem like a simple matter for the Democrats to defeat Trump’s Republicans. The enthusiasm is certainly on their side. The liberal rank and file are more energized than they have been for years. Political novices are signing up to run for office across the country. Democrats are well ahead in nearly any poll you care to mention. But still, I give them only a fair-to-middling chance of ultimately defeating him.

Why? Because you go into political combat with the party you have, not the party you wish you had. And the Democratic Party we have today is not particularly well suited to the essential task of beating Donald Trump.

It is true that the Democrats’ fighting instincts have been aroused by the ascendancy of Trump, and this is a healthy thing. Fewer and fewer American liberals worship at the shrine of bipartisanship, as they have done for most of the past few decades. Instead, they are outraged. They are horrified at what has happened. Descriptions of Republican misgovernance that were formerly considered extreme are now taken for granted.2 That a quality person like Hillary Clinton, who prepared to be president all her life, should be bested by this vulgar, racist ignoramus — it is unthinkable. It is unacceptable.

I understand this reaction. I have felt it myself. But it has led the Democrats into a trap familiar to anyone with experience of left-wing politics: the party’s own high regard for itself has come to eclipse every other concern. Among the authorized opinion leaders of liberalism, for example, the task of deploring and denouncing the would-be dictator has crowded out the equally important task of assessing where the Democratic Party went wrong. Indeed, the two projects appear to them to be contradictory — they find it impossible to flagellate Trump one day and examine themselves the next. Of the two, it is introspection that must hit the bricks. And it is uncompromising moral stridor that has come to dominate the opinion pages and the airwaves of the enlightened — a continuous outpouring of agony and aghastitude at Trump and his works.

This is unfortunate, because what happened in 2016 deserves to be taken seriously. This country of 320 million people was swept by a tidal wave of populist rage. Alongside the ugly eruption of bigotry there swirled perfectly natural concerns about deindustrialization, oligarchy, the power of big banks, bad trade deals, and the long-term abandonment of working-class concerns by the Democrats. I am condensing many strands here, of course, but what is important is that for all its awfulness, there were elements of the 2016 revolt that liberals ought to heed.

But most leading Democrats can’t seem to see any of that. They don’t know what to make of Trump and his supporters, so violently does Trumpism transgress the professional norms to which they are accustomed. It is distasteful to them that they should be required to learn anything from a clown like the current president — that they should have to change in any way to accommodate his preposterous views. And so they cast about for leaders who might allow them to prevail without doing anything differently: a celebrity who might communicate better, a politician who might turn out the base more effectively. They devour articles about Trump voters who have had a change of heart and now beg forgiveness for their sins. They chide other liberals whom they regard as insufficiently enthusiastic about the Democratic Party. Above all, they dream of a deus ex machina, a super-prosecutor who will bring down justice like fire and reverse the unfortunate results of 2016 without anyone having to change their talking points in the slightest.

The price of going down this path is that it encourages passivity and delusions of righteousness. Their job, Democrats think, is to wait for Trump to be led out of the Oval Office in flex-cuffs while they stand by anathematizing him and his supporters. They don’t need to convince anyone. They need only let their virtue shine bright for all to see.

Now, this is a morally satisfying position, and it might even work. Maybe some prosecutor has really and truly got the goods on this scoundrel. Maybe the outpouring of anti-Trump feeling will suffice to defeat him: being against him may be all that voters require from a candidate in the midterm congressional contests.

On the other hand, in the vast catalogue of social posturing, there are few more repugnant sights than rich people congratulating themselves for being righteous. In particular, it is a terrible way to win back the blue-collar white voters who were responsible, even more than were the Russians, for Trump’s win. For insight into the thinking of this cohort, I turned to Working America, an affiliate of the AFL-CIO, which canvasses working-class neighborhoods around the country. Karen Nussbaum, the organization’s executive director, was blunt about it: “If Democrats just want to keep piling on Trump, that will be the way to get Trump reelected.” Resisting the president’s agenda is important, of course, but when Working America canvassers knock on doors, she added, they never point the finger at Trump voters. “We don’t say, ‘Aren’t you sorry you voted for him?’ That’s the last thing you should talk about with them.”

The real concerns of these voters, Nussbaum told me, are such bedrock matters as jobs, wages, schools, Social Security — the very things Trump made such a loud display of pretending to care about in 2016. The Democrats, of course, did their pretending in the other direction that year. They identified themselves with globalization, with trade agreements, with Silicon Valley, addressing the public as complacent representatives of this triumphant economic order. It was an old line of patter, the philosophy of the Nineties, reiterated mechanically at a time when no one believed it anymore.

Yes, the Democrats also promised to “break barriers” so that the talented could rise regardless of race or gender. The system itself, however, was judged to be in excellent health. As President Obama put it just before the election, “The economic progress we’re making is undeniable.” Or, as Hillary Clinton liked to say, “America never stopped being great.”

It was exactly the wrong message for an enormous part of the population. Stanley Greenberg, a veteran Democratic pollster who understood the Trump phenomenon better than many others, told me recently that the Democrats’ mistake was “selling progress at a time of growing, record inequality, stark pain, and financial struggle.” Even when the Democrats could see the obvious shortcomings of such an approach, they felt they couldn’t change. “How do I talk about their pain without sounding like I’m criticizing President Obama and his economy?” Hillary Clinton asked Greenberg during the campaign, according to a 2017 essay he wrote for The American Prospect. “I just can’t do that.”

That dilemma persists to this day. How do Democrats change course without sounding like they’re criticizing Obama or the Clintons — or, by extension, the neoliberal fantasy that has sustained the party since the Nineties? The answer is that they can’t, and so they don’t. They would rather sit back and expect Robert Mueller to rescue them. They would rather count on demographic change to give them a majority somewhere down the road. So they “do nothing and wait for the other side to implode,” observed Bill Curry, a former adviser to President Clinton who has emerged as one of the Democratic Party’s strongest internal critics. “That’s been their strategy for most of my adult life. Well, how’s that been working out?”

Curry continued his critique. The party, he said, desperately needs to get over its infatuation with its glorious past: “The mistakes of the Democratic Party are the mistakes of Obama and Clinton. Taking responsibility for those mistakes means holding them accountable. And so many people have such deep, positive feelings for Obama and the Clintons that they can’t bear to have that conversation.” His conclusion was as blunt as what I heard from so many others: “Trump wins by the Democrats not changing.”

This sounds dreadful to me, but I suspect that for a lot of prosperous liberals, it wouldn’t be such a bad thing. For them, there’s an alternative to political victory: a utopia of scolding. Who needs to win elections when you can personally reestablish the rightful social order every day on Twitter and Facebook? When you can scold, and scold, and scold, and scold. That’s their future, and it’s a satisfying one: a finger wagging in some deplorable’s face, forever.

I paint a gloomy picture here, I admit. If the economy zooms, I have conjectured, Donald Trump has a good chance of being reelected. If economic conditions don’t change and Democrats play out their strategy of indignant professional-class self-admiration, they have only a fair chance of chasing him out of office — after which they will undoubtedly be surprised by some new and even more abrasive iteration of right-wing populism.

What I want to focus on now is how right-wing populism can be defeated more or less permanently. Donald Trump will never seem like a natural or inevitable president to me — not merely because he is a cad with a cantilevered comb-over but because right-wing populism is itself a freakish historical anomaly. Yes, I know, it has been running strong for decades. By its very nature, however, it is a put-on, a volatile substance, riven with contradictions: it rails against elites while cutting taxes for the rich; it pretends to love the common people while insulting certain people for being a little too common; it worships the workingman while steadily worsening his conditions.

Nor can I reconcile myself to the sort of prosperous, pious liberalism that predominates nowadays, a nice suburban politics that finds it easy to love Google and Goldman but can be downright contemptuous toward the desperate middle class that liberalism was born to serve. To my eye, the passionless technocrats it has repeatedly chosen as its leaders seem as unnatural as Trump himself.

But maybe that’s just me, still dazed by what happened on Election Night in 2016. Nothing in politics seems right anymore. I keep assuming that a society plumbing the depths of inequality ought to be a society turning to the left — that a populist moment ought to be a Democratic moment — that the natural agent of public discontent ought to be the more liberal of the two parties. That one fine day we will give the TV set a smack, everything will snap back into focus, and Americans will clearly understand what a mountebank Trump is. That in January 2021, they will eject him from the White House in disgrace — a Herbert Hoover with a spray-on tan, a scowling mistake we will never make again.

What might Democrats do to bring that about? A while back, I used to write earnest essays exhorting President Obama to do this thing and that during his final years in power. Enforce antitrust! Prosecute financial fraud! Today, however, the party has no national power to demonstrate its solicitude for the crumbling middle class. Republicans have pretty much captured it all.

What is left to liberals today is positioning and public declaration. They must do the obvious, of course: find a way to capitalize on the incredible political blunders Trump has made, pointlessly disparaging almost every possible demographic. “He is pissing people off at such an accelerated rate,” marveled Keith Ellison, the representative from Minnesota who serves these days as the deputy chairman of the Democratic National Committee. As ugly as Trump’s ravings may be, they can’t help but mobilize the Democratic base.

Getting those voters out is the tactical challenge. The larger, strategic question has to do with the Democratic Party’s identity. Does it accept the Republicans’ invitation to continue on as it has before, making itself more and more into an expression of professional-class disdain? Friend to the enlightened financier, careful curator of the silicon millennium? Or do the Democrats rediscover their roots as the tribune of blue-collar America? For me, the answer has never been more obvious. For others as well. “Sit with some folks who work for a living” is Ellison’s prescription. “Ask them what they want. And you’ll win.”

In 1941, President Franklin Roosevelt set down his vision of American political history, in which two “schools of political belief,” liberals and conservatives, fought endlessly for primacy. Regardless of what it was called at any particular moment, he wrote, the liberal party “believed in the wisdom and efficacy of the will of the great majority of the people, as distinguished from the judgment of a small minority of either education or wealth.”

What Roosevelt did not foresee was a party system in which the divide fell not between the few and the many but between the small minority of education and the small minority of wealth. How could he have known that his great majority would be split in two and offered a choice between enlightened technocrats on the one side and resentful billionaires on the other?

Get that great majority back together, I think, and it would be unstoppable. There is really only one set of successful politics for an age of inequality like this one, and it naturally favors the party of Roosevelt. Trump succeeded by pretending to be the heir of populists past, acting the role of a rough-hewn reformer who detested the powerful and cared about working-class people. Now it is the turn of Democrats to take it back from him. They may have to fire their consultants. They may have to stand up to their donors. They will certainly have to find the courage to change, to dump the ideology of the Nineties, the catechism of tech, bank, and globe that everyone now knows is nothing but an excuse for an out-of-touch elite. But the time has come. History is calling.